“Artistic experimentation is shit … Two actors, some lines, and an audience, that’s what I say.” So declares Robert (Patrick Stewart) to his scene partner John (T.R. Knight), invoking the Holy Trinity of playwright David Mamet — and adding, for emphasis, the master’s traditional benediction: “Fuck ‘em all.” Ah, clarity: so rare on the stage, so bracing, so invigorating … and yet so spare, so chilly and ephemeral.

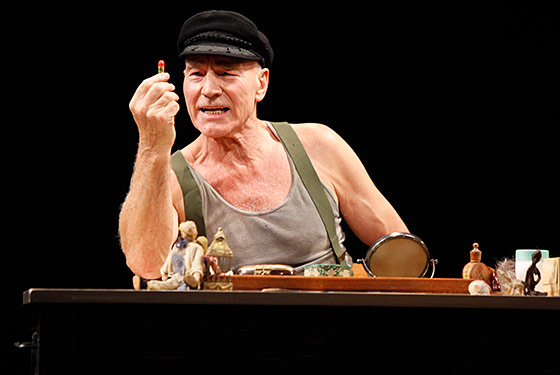

This is A Life in the Theatre, Mamet’s revived 1975 two-man comedy (though one and a half men might be a more accurate head count) about an older journeyman actor (Stewart, vital and precise), on whom the spotlight is steadily dimming, and a younger one (Grey’s Anatomy’s Knight), who’s still got that green and hungry look. Together with director Neil Pepe (Mamet’s anointed helmsman and the stopwatch behind the brisk Broadway revival of Speed the Plow), this seemingly mismatched pair make a solid team, executing Mamet’s succinct pseudo-existential riff with focused energy and crisp comic timing.

You will laugh, most likely, though perhaps not as hard as you might have had you felt a bit more of the show’s inner ache and a shade less of its slightly gluey buffoonery. The play itself is a simple little machine of superficially Pirandellan construction: We follow the actors’ backstage lives, taking regular breaks to watch them perform in a (broadly awful) play directed at the back wall, which is designed to suggest the unguessable depths of An Audience. Robert begins as mentor, but quickly goes the way of all Mamet pantaloons, from Shelly Levine on down: The more he yammers on about the Work and the Business, the faster he’s overtaken by a younger, stronger, more cipherlike rival. It’s a tricky business, casting-wise, as the more powerful actor of the pair is likely to be playing Robert — and Stewart is power, a bare bulb of theatrical incandescence. But Knight, far from being blown (or beamed) off the stage, knows his place on it and stays there. His job, as prototypical Mamet man, is to hunt for his objective. He has the big, dead eyes of an innocent predator, one who’s more dangerous than he looks. As character and actor, Knight does his office admirably, without ever exceeding its limits or even looking like he’d want to.

But then, who’d be suicidal enough to want to get between Stewart and an audience? No one gets at the tragic dignity of a powerful man in irresistible decline quite like Stewart (and here I direct your attention, without shame, not only to his work in Macbeth and The Ride Down Mount Morgan, but to his towering, tumbling, still-unequaled performance in the series finale of Star Trek: The Next Generation). “Sound!” he declares, triumphantly and foolishly, “The crown prince of phenomena!” Embarking on a long and ultimately nonsensical digression about how sounds and smells emanate from the innermost self, Stewart’s Robert witlessly reveals himself a gaseous and empty person, vulnerable to the slightest pinprick. But Stewart himself is a creature of such remarkable vitality, it’s a little hard to buy him as a guy at the end of his powers.

Little of the text has been updated (though an eleven o’clock mini-logue seems to have been added for Stewart), and Pepe has abided by a core Mamet principle and directed only the text. (Mamet, in his recent book Theatre and Other Treatises, has come out as a sort of Antonin Scalia of Theater: He’s an originalist, believing the script to be complete unto itself and allergic to dramaturgy and interpretation.) The actors have responded with the rhythms of klassic komedy, which the play invites. The plays-within-the-play are all intentionally bastardized pastiches of Chekhov, Shaw, O’Neill, etc., and Mamet invites us to find acting and actors ridiculous for all the reasons we already find actors ridiculous: Look at them, men in tights at the balance beam, fussing over their “art”! Watch John try to fix Robert’s broken zipper with a safety pin — could the not-so-vaguely homoerotic competition of these greasepaint frenemies be any more obvious? And why, exactly, are the plays all so high-school awful, as written and as acted? Is theater, finally, just too effete and silly a form for David Fucking Mamet?

Troubling stuff like this comes to the fore when Life is stripped to its fundamentals. And fundamentals are, in the end, what this production is all about. Timing, holding focus, taking and ceding the stage, winners and losers, doms and subs. (Nowhere does this hit you harder than “the famous lifeboat scene,” a sort of Winslow Homer brought to life, where Stewart and Knight seesaw on a huge swinging dinghy, up and down, crudely trading bad lines in terrible dinner-theater pan-Britannia accents.) Reversals and wrestling holds are the stuff of life, according to the Mamet schema. But he’s left a lot of white space between the thrusts and parries of the text, and that space just hasn’t been colonized with a whole lot of (sorry Dave, I know you hate this phrase) Human Feeling. Is there, at bottom, anything at stake in the relationship between these two men? Do they even like each other? Mamet leaves these questions open in his script, and Pepe, a good soldier, hasn’t volunteered any theories. The actors dutifully play the text. Marks are hit, laughs are obtained on schedule and in abundance, a fine time is had by all, and if something intrinsic is missing — an aftertaste of pathos, say — you barely notice until you’re being mushed toward the exit. Perhaps that pleases the master, but it leaves us a little cold, out in the audience. We’re laughing, and then we’re leaving. Personally, I’d like a little more out of life, feigned or not.