Today sees the opening of two remakes of eighties cult hits that play off of name recognition: Conan the Barbarian and Fright Night. The first has been kept culturally relevant mostly from Arnold Schwarzenegger’s constant references to it as governor, while at this point the second title strikes a chord mostly with those who spent insomniac evenings watching it rerun on USA before there were more options on cable. So what value do these nostalgic, more fuzzily remembered titles really have to today’s audiences?

Let’s start with Fright Night: Its target is young women, who are the historically predominant demo for horror, according to Geoffrey Ammer, a former president of marketing at Columbia Pictures, Revolution Studios, and Marvel Entertainment. But shouldn’t its title also, in theory, appeal to older women who were screaming teens when the original came out in 1985?

However, according to NRG audience polling data leaked to us by a studio source, nearly three fourths (74 percent) of women under 25 were aware of the Colin Farrell movie (up from 69 percent on Sunday), with one in four of them expressing “definite interest” in seeing it. This augurs a modest opening, one made all the more modest because the number of older females with “definite interest” is actually decreasing, dropping from 22 percent to 20 percent since Sunday. Older women are less prone to go to horror movies anyway, and as the demo who would most recognize the title, they are getting less intrigued the more marketing money the studio pours on. (Still, its young female audience and a recent uptick in young males suggests it might make $17 million and finish in second place.)

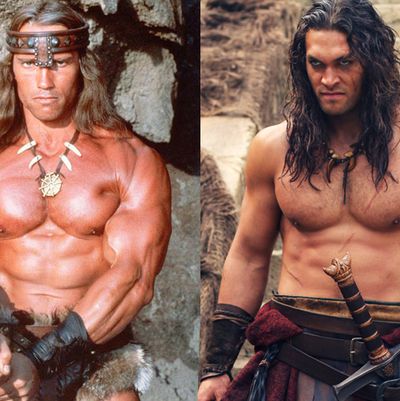

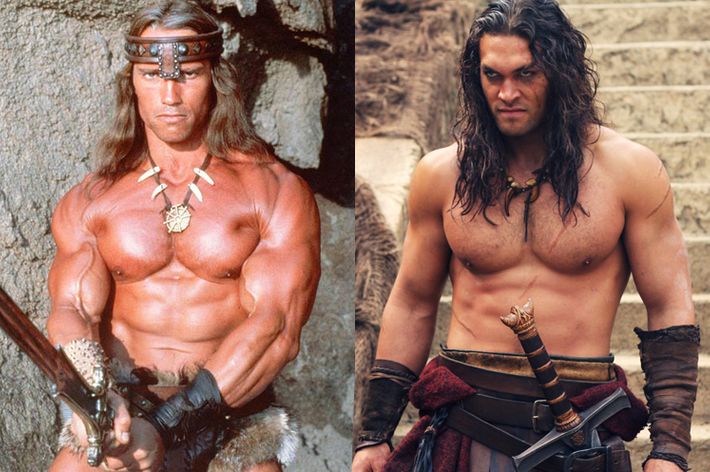

On the other hand, the primary audience for action-adventure movies is, unsurprisingly, young men. So, once again, older males who saw the original Conan the Barbarian in 1982 are the ones who, based on the title, would seem most nostalgically driven to see another warrior crush his enemies, see them driven before him, and time permitting, hear the lamentations of their women. In this case, men over 25 are more aware of the new Conan than those under 25 (89 percent versus 80 percent), but there is no difference whatsoever in their level of definite interest (37 percent) in seeing the remake. (This suggests a $15 million opening and a fourth-place finish, but doesn’t mean it can’t be profitable regardless.)

“If you look at both films, neither [title] is meaningful to older audiences right now,” says Ammer. “It’s been too long.” So why bother with resuscitating an old title when you could just as easily create a new one with the same basic premise, but different enough not to be sued over? After all, in these vampire-clogged times, it wouldn’t be suspicious if a studio came up with its own bloodsucker-next-door concept. “Studios remake these movies because they often already own the title,” says Ammer. But it’s more than that. After all, it wouldn’t cost a studio any more money to hire a writer to write an original screenplay than it would to have him or her write one based on an older film. The real appeal of an old title is more superstitious: The studios use them, says Ammer, because “they know it’s worked in the past.” Even though it’s an entirely different movie made by different people for a different generation, the idea is, hey, the title worked before, why not give it another shot? For all of Hollywood’s supposed liberalism, studios, like their audiences, are quite conservative. Genre is the most predictive aspect of a film’s future results, and then title, so why not double down? A remake of a successful genre film allows a studio the greatest possible risk reduction.

Of course, dismissing warmed-over art is an ancient pastime — one dating back to before the nineteenth century, when Italian poet Giacamo Leopardi lamented that “there are some centuries in which the art and other disciplines presume to remake everything because they know how to make nothing.” But in today’s Hollywood, the truth is just the reverse: They make nothing precisely because they know how to remake everything.