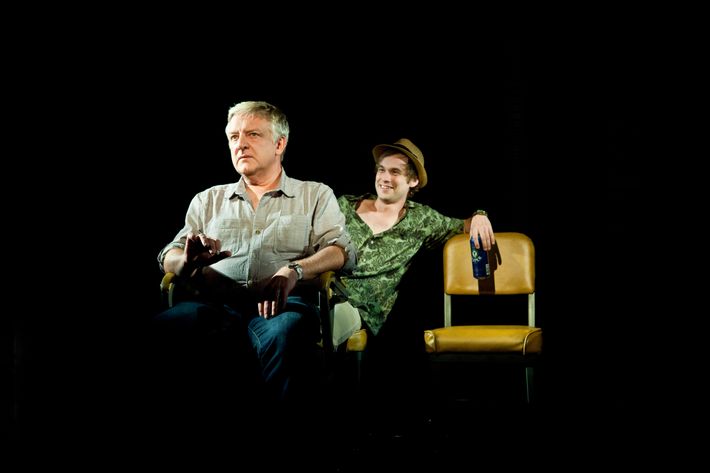

Simon Russell Beale, one of the very finest actors working today, is the best thing about Bluebird, a revival of a 1998 one-act by Gen-X British playwright Simon Stephens. That’s hardly surprising: Beale — a Brit minimalist with superb comic timing, who infuses his sad-sacks with wily vitality that only deepens the pathos — has often been the best thing about the productions he’s in. What’s odd about Bluebird is the eye-juddering mismatch of star and material. It’s not just that Beale, who’s 50, is wrong for the part, though he is, by nearly a generation. Jimmy — the tormented London taxi driver whose cab is the backdrop for 90 percent of the action — was written by a mid-twentysomething for a mid-thirtysomething to play: Beale might’ve just squeezed into it when the show first opened in the Clinton era, but Jimmy wasn’t his type back then and isn’t really his type now. Reportedly, that’s what attracted Beale to the role — the challenge of an awkward fit — and he’s more or less rewritten the role around himself. As an older man, with most of the anger beaten out of him, this newer, older Jimmy is no young tragedy; he’s a ghost, fading rapidly into the upholstery. Yet he’s far more multidimensional than any of the people or situations he encounters on the wet streets of nighttime England. Jimmy, an insomniac and sometimes-humanist, is out-of-joint with time and space, stuck in a period piece without a period. Why doesn’t he use a cell phone? Oh, right: because it’s 1998.

Only it isn’t. Bluebird seems to be set in that highly cinematic Everyplace, Anytime, where writers often go for stories when they’re hunting far beyond the precincts of their life experience. It’s not such an awful place to spend an evening, and there are moments in the show when Beale holds your attention so authoritatively — with spare dialogue, a tiny grimace, an eye cut to the rear-view mirror and back — that you suspect him of practicing some subtle mesmerism. He’s so much more present than anything else onstage, the play starts to feel like his private reverie. Nothing else matters but him, and I’d argue that’s a bad thing. We’re invested in nothing, not the source of Jimmy’s guilt (maudlin, rote, almost unimportant), not the identity of the woman he keeps trying to phone (guessable, boring, too easy), not what he derives from his menagerie of customers (which include would-be murderers, petty criminals, a prostitute, and a budding nymphomaniac — in other words, Characters), and certainly not his mysterious former occupation. (He was, I am very sorry to report, a novelist. Who turned his back on the world! Oh, dear.) Stephens has a gentle and humane style here (I’m not familiar with most of his other work), but the actual content of his drama feels highly suspect, blatantly derivative, and extremely green. Stephens seems to have written this when he was a young playwright coming into his powers, and Beale is a middle-aged actor at the peak of his. The gap there is a wide one, and, intermittently, sparks arc across it. Ultimately, though, you find yourself staring at a void and thinking seriously about your ride home.