Happy Hour, the latest string of crappy from filmmaker Ethan Coen (half of the Coen brothers), is a powerful argument for writing plays. Not that Coen has written one. He’s actually written three non-plays—barely even sketches, really—all making use of the aloof deadpan-existentialism that is the Coen brand, never to particularly flattering effect.

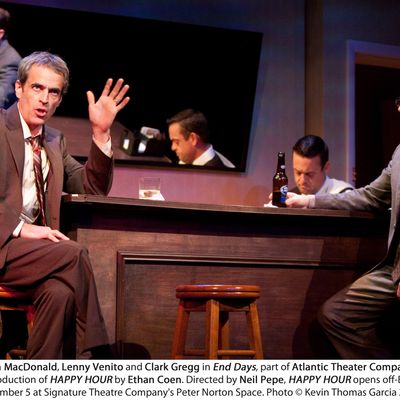

The themes of the night are rage, depression and intoxication: “End Days” is about a barfly (Gordon Hoffman) on an apoplexy bender, venting his paranoid and apocalyptic worldview to anyone unlucky enough to get caught inside his bloviating radius; “City Lights” follows the travails of a volcanically unmellow seventies session musician (Joey Slotnick) and a lonely, recently-dumped That Girl (Aya Cash); “Wayfarer’s Inn” zooms in on a hotel room occupied by two businessmen, one a morally untroubled Holiday Inn hedonist (Clark Gregg), the other a sensitive type in a deep despond (Lenny Venito). I can say, with confidence, that you now know all I know about these playlets. They’re sketches of sketches, each a thimbleful of one-liners dissolved in a situation so basic, it’s barely situated.

That ought to be enough. Who better than a to entrust with material that’s arid, angry and absurd, the three As of Coenism? But as was the case with his earlier “Offices,” maximum aridness mated to minimal absurdity and undefined anger comes out looking less like an original piece and more like weak-sauce Mamet parody. (Especially when it’s directed by the arithmetically minded Mamet-collaborator Neil Pepe, who sounds like he’s counting the syllables.) I didn’t see Almost an Evening, the compilation that started Coen’s theater jag, but I suspect it’s his most honestly titled stage production to date.

The most frustrating part of Happy Hour is the blown potential. Coen’s obviously a gifted writer. He can quickly and efficiently establish a sort of room-tone of comic, cosmic dread. He’s got fury to spare, though it is, to be sure, a narrow fury, that of a certain class of man at certain stage of life. Inside that idiom, he can land a joke like nobody’s business. But Coen seems to be counting the ambrosial effects of editing and cinematography to make what he’s written dance. Short these crutches, it’s as if he refuses to finish exploring the possibilities of what he’s begun—and then apparently convinces himself that the very unfinishedness is the point, a kind of pomo gotcha. Very po’ indeed. So please, no mo’. Not till there’s a completed play.