After half a century of newsprint and ink, Marvel Studios has finally turned its one true supergroup, The Avengers, into celluloid reality. That’s supergroup in the rock-band sense — a bunch of world-beating icons who made their bones before joining together struggle to put ego aside, but tend to bicker and occasionally storm out for solo projects. When the concept of the superhero superteam was first introduced in the forties, the first group of all-stars were kind of square and spent more time politely debating than clobbering. It was only as the decades went on that both DC and Marvel embraced the idea of synchronized violence and team-wide dysfunction, the building blocks of Joss Whedon’s new film version. Before you head to the theater this weekend, a comic book history lesson is in order.

In the comics, this kind of dream-team assembly of winners is old hat; it goes back to 1940, a few years after baseball’s first All-Star Game and during the run-up to World War II alliances — in short, a time of team-ups. With a mandate to grab some attention for characters who weren’t Superman or Batman, an editor and writer at DC Comics threw the Flash, Green Lantern, and also-rans like Hour-Man and Johnny Thunder into All-Star Comics, calling them the Justice Society of America. However, instead of joining to mete out justice with their fists, they convened only through Robert’s Rules of Order; the group sat at conference tables, pounded gavels, and recorded meeting minutes before rushing off to their own adventures. Timely Comics, the company that would eventually be known as Marvel, answered with their All-Winners Squad, whose meetings featured just as many bureaucratic longueurs as the Justice Society’s, but at least its membership included the company’s biggest guns: Captain America, the Sub-Mariner, and the Human Torch. But Timely’s knack had always been for heroes who rubbed each other the wrong way, and because the All-Winners were following in DC’s upright-citizen mold, they were made to be more respectful, almost dull. All-Winners Comics folded after two issues.

In the early sixties, it was DC’s introduction of another supergroup — the straight and narrow, stalwart Justice League of America (Flash and Green Lantern and Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, plus others) — that reportedly spurred Marvel back into the hero game after having given them up in favor of horror, western, and sci-fi comics. With artist/co-scenarist Jack Kirby, editor and writer Stan Lee introduced a series of costumed adventurers whose neuroses and flaws stood in contrast to the breezily confident JLA: the Fantastic Four (a dysfunctional family combo), the Hulk (violent blackout issues), Thor (a cripple), Iron Man (Howard Hughes with a heart condition). And Lee and artist Steve Ditko rolled out Spider-Man, an angsty, guilt-ridden teen. It was these flashes of darkness that made them so fascinating.

That was also the major obstacle when Lee and Kirby tried to unite Iron Man, Thor, the Hulk, Ant-Man, and Wasp to revive the supergroup formula in 1963 with The Avengers. Removed from the contexts of their neurotic personal lives and jammed into pure-battle adventures, they came off as simple, child-like strongmen chirping inane dialogue. Iron Man, still learning about armor aesthetics, was a rounded, clunky, gold-painted heap. Thor’s Elizabethean jargon only exacerbated his fish-out-of-water cluelessness. The Hulk was an idiot. In those earliest issues, the only charms were Kirby’s elegant page designs and the novelty of worlds colliding.

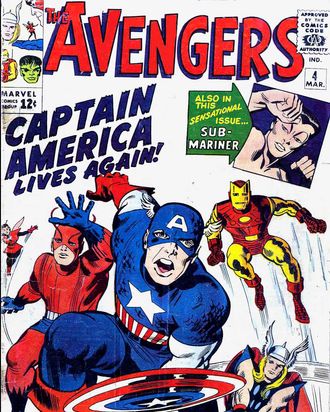

But in the fourth issue, when Captain America joined The Avengers, the title found the tragic hero that it needed at its center. Created by Joe Simon and Kirby twenty years earlier, Captain America had faded away at the end of the forties, briefly returned as a McCarthy-era commie smasher, and was then discarded again. His last solo issue appeared in 1954, but he resurfaced in The Avengers when the younger heroes found him in the sea, unconscious and encased in a block of ice, his youth preserved. The revived Captain America was wholesome and admirable, just like he’d always been, but now he was a man out of time, a walking anachronism prone to bouts of melancholy and confusion about what had happened to his country. Understandably so: The issue in which he leaped back into action hit newsstands only weeks after JFK was assassinated. The other Avengers began opening up, too; it became more of a team, and less of a free agency.

By 1965, though, Lee had gotten tired of trying to choreograph the crossover continuity between the Avengers and its members’ solo adventures in their own titles. In Avengers #16, Thor, Iron Man, Ant-Man, and the Wasp announced that they were taking “leaves of absence” (the Hulk had long since stomped off) and Captain America was stuck with the new recruits: Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch, a brother-and-sister team who were reformed X-Men villains, and Hawkeye, a purple-tunic-wearing carnival marksman who’d previously battled Iron Man (it was only to impress the Black Widow, a Red spy femme fatale decked out in mink stole and pearls). Later writers would dub this lineup, infamously low on star power, “Cap’s Kooky Quartet.” The Avengers, now saddled with underdogs, were no longer a supergroup.

Marvel didn’t introduce more hero teams until 1971’s The Defenders (which threw aloof loners Dr. Strange, the Sub-Mariner, and Silver Surfer in with the monosyllabic Hulk, who punctuated their BBC-drama drabness with violent tantrums). In 1975, The Champions, Marvel’s third attempt at a supergroup, relocated ex-X-Men Angel and Iceman, Ghost Rider, Hercules, and a rehabilitated Black Widow (unrecognizably clad in a skintight leather jumpsuit) to Los Angeles, where they eventually realized, after sixteen issues, that they had neither chemistry nor a particularly impressive track record of saving the world.

Which, once again, left the Avengers. The roster regained its stars during the seventies, and by the early eighties Captain America, Thor, and Iron Man were all back in the fold. But the team’s most popular characters were always, in effect, on loan from their own titles, where the truly memorable, modern story lines were situated: Captain America contended with Watergate, Iron Man battled alcoholism, Thor surrendered his hammer, the Hulk got smart. In The Avengers, they mostly fought. Like a Busby Berkeley musical, the comic compensated for meager character development with a host of colorful costumes and graceful athletics.

At the beginning of the 21st century, Marvel launched an alternate version of the group called The Ultimates, published alongside the ongoing old-school original (it was a kind of user-optional reboot, in a sense). In this version, Nick Fury — in traditional Marvel lore, a grey-templed, greatest-generation superspy, but now a dead ringer for Samuel L. Jackson (this, amazingly and psychically, six years before Jackson first played him in Iron Man) – organized a team of super-powered living weapons for the United States. But now Thor was a longhaired WTO protester, and Tony Stark a nihilistic, wisecracking ratfink. Captain America’s likeness was based on Brad Pitt; Iron Man’s on Johnny Depp. The casting précis was complete, and the art looked like widescreen storyboards. It was a “realistic” version of the Avengers, in the way that contemporary comics readers defined the term: pessimistic, violent, and more concerned with repercussions than with moments of transcendence. Interesting, but these Avengers hardly felt like the kind of heroes that Disney would want to work with.

So Joss Whedon’s Avengers splits the difference, lines up the more recent rejiggerings of character backstory and industrial-complex subtexts with the big, dumb, primary-color fun of the early days. The CGI fights are fun, and the banter is sharp, but there’s hardly ever a question of who will prevail, or who will survive; in true supergroup fashion, they’re all signed up for sequels. So the best parts of The Avengers are the glimpses into all-too-human behavior. For me, its riveting centerpiece is a conference-room showdown between Iron Man and Captain America about utilitarianism and the use of power. It’s a quiet interlude in the midst of a movie that is the climax to decades of property-synergizing strategy, placed solely to remind the audience that there can still be stakes, even when everyone is preordained to be a winner.

Sean Howe is the author of a forthcoming history of Marvel Comics, to be published by HarperCollins in October.