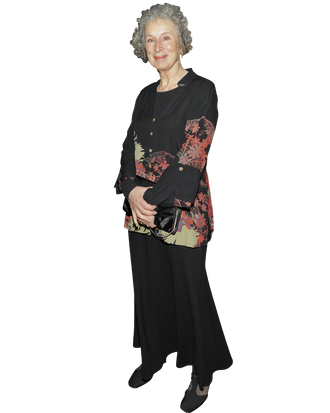

Margaret Atwood is helping promote a new film called Payback, a documentary spawned from her 2008 collection of essays Payback: Debt and the Shadow Side of Wealth — which, despite the title, is not the economic work it sounds like. Her definition of debt is more flexible, and includes moral debts and the acts of revenge that they might inspire. (Payback opens with a blood feud between two families). With her classic work The Handmaid’s Tale, about a dystopian future in which women have no control over their reproductive rights, being cited by politicians during this campaign season and its influence on the recent blockbuster The Hunger Games, Vulture thought it high time to check in with the author, who was in town to kick off Payback’s premiere at Film Forum.

Have you had a chance to read or see The Hunger Games? The games are designed for the districts to pay back the Capitol for a past rebellion, via the lives of their children, like the heroine Katniss Everdeen. It seems to be inspired in part by elements of The Handmaid’s Tale, Oryx and Crake, and Year of the Flood, especially in terms of the structure of postapocalyptic society, how the disenfranchised are “chosen” for an honor that is anything but …

In kind of a game show? So, basically it’s Painball from Year of the Flood in which people are pitted against other people so other people can watch it on TV? And the origin of that of course is paintball, which is a real thing! It’s always nice to have people see the beauty of one’s ideas. I’m flattered. [Chuckles.] It sounds interesting. Some of these things go way back, mythologically. How did she end up in this position?

Because there’s a lottery, and her sister was chosen, and so she volunteers to take her place.

Shirley Jackson! How old are they?

Between the ages of 11 and 18.

Theseus and the Minotaur! Love it. And so they put these people in a very large area? It’s Painball. Same idea. If you survive, will they let you out?

I don’t want to spoil it too much for you.

That’s okay — I can guess. I haven’t written my third one yet, so whatever’s in it can’t be used in The Hunger Games. [Laughs.] I’m in the middle of it. It’s called MaddAddam, which is the only group we really haven’t delved into so far in that world. Oryx and Crake was inside the very well-to-do protected compounds, and Year of the Flood was God’s Gardeners, and then there’s a splinter group that goes off with Zeb. So Toby and Zeb and the people in the MaddAddam group, and you also have to have Jimmy Snowman, Amanda, and Ren, because when the second one ends, they’re all there. I’m about halfway done, so it’ll be out in 2013.

You joked recently that librarians moved The Handmaid’s Tale from the speculative fiction section to current events.

It’s being so referenced particularly in relation to state Republican–run governments in this country, things saying The Handmaid’s Tale is coming true, to which I footnote, “Not with the same outfits.” [Laughs.] But it’s been a film, an opera, and now it’s going to be a ballet! This choreographer called Lila York is doing it, and she said, “We can’t put the full skirts on them.” When they put on the opera in Toronto, it attracted a whole new audience of operagoers — black leather, piercings. It was quite the opera. I wish it would come here! When all of this first appeared, people were afraid to touch it, but now the other fear is greater. What was it, a Georgia state representative who said women should have to carry a disintegrating dead baby because cows and pigs did? That can kill you. Has it not occurred to anybody? Apparently not. And women generally don’t appreciate being compared to pigs and cows.

What are you reading right now?

I’m reading the journals of Fanny Kemball, who was a very well-known British actress in the 19th century who married an American who inherited the family’s slave plantations in the South. So she went down there, and she got a lot of animosity for writing about that. You weren’t supposed to. You were supposed to say it was all jolly, they were treated well, they wanted to be there, and she was giving a non-reality-TV description of what was going on.

You touch on that in the film with the migrant workers — who are the new slaves, of a sort.

Very lucrative. It’s very lucrative to work people to death, and that’s what the slave owners were doing. Some of them, they would just switch over people every seven years, because it was cheaper to buy new ones instead of maintain the ones they had. It’s all about the lowest rate and profitability. What Americans are competing against are workers in China who get paid very little and work twelve hours a day, seven days a week, and you can’t do that in this country, although they came close with the tomato pickers.

You discuss the idea of debt and revenge as it pertains to Dickens. What about something more contemporary, such as the show Revenge?

Absolutely. It’s The Count of Monte Cristo to the T. That’s a visceral story that we can all identity with, and it’s an emotion we all have — if someone does something bad to us, we do want to get them back in some way. I’m just reading a book on Elizabethan revenge plays, and there’s a lot of disguising yourself as somebody else and getting back at people. It is an ancient plot.

Are you working with Sarah Polley for her upcoming film adaptation of Alias Grace?

Yes. I’ve known Sarah for about ten years. She’s a grand girl. When she wants me, I’m there. Even if it’s, “What sort of underwear did they wear?” “What did they eat?” One of the first people interested in the role of Grace was Cate Blanchett, but that was a long time ago and then she got pregnant. Sarah really has a handle on it, though. I did my first film script in 1970, 1971, with The Edible Woman, which never got made. I was so stupid in those days. I didn’t know anything about what I should be doing.

Would you want to make a cameo in Alias Grace?

Oh, absolutely. Dress me up. Put me in the prison. I can be somebody stirring a cauldron.