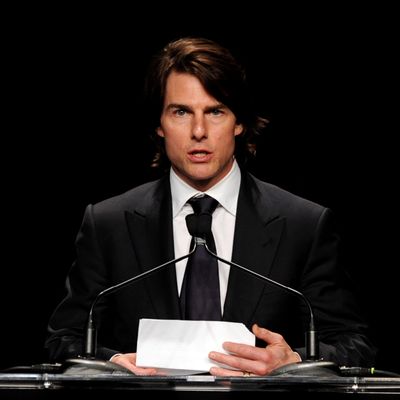

The Church of Scientology has awarded just 80 people their coveted Freedom Medal, which recognizes “exemplary courage and determination…for bringing greater freedom to mankind.” But only one person in the Church’s 60-year existence has ever won their Freedom Medal of Valor award: Tom Cruise, the Church’s Golden Boy, who was recruited in the eighties and groomed to be Scientology’s best advertisement. And so it proves ironic that the religion, which has historically been so adept at squashing bad press through lawsuits and intimidation, now finds itself under an onslaught of negative scrutiny — and it’s largely thanks to Cruise. Once the Church’s most treasured member, he may now prove to be its greatest liability.

Tom Cruise joined Scientology under the tutelage of his then-wife, actress Mimi Rogers, herself raised in the Church. (Rogers is rumored to have left the Church after her divorce from Cruise.) Then, in his mid-twenties, Cruise was enjoying the most successful period of his career, as he transitioned from teen heartthrob to Serious Dramatic Actor with roles in The Color of Money and Rain Man. According to Janet Reitman’s acclaimed book Inside Scientology, Cruise initially attended the Church’s auditing sessions (the process through which Church members push through their layers of emotional baggage and become “clear”) quietly and secretly, under his birth name Thomas Mapother. As he warmed to the procedures, he was turned over to the Church’s Celebrity Center and eventually formed a deep bond with David Miscavige, the Church’s controversial leader who took over following the 1986 death of its founder, L. Ron Hubbard. Miscavige, according to Reitman, told staff members that Cruise’s recruitment could “change the face of Scientology forever.” The actor was escorted out to the Church’s secret desert oasis in Gilman Springs, California, a place where he could immerse himself in the Church away from prying eyes.

Cruise soon became not just a full member of Scientology, but its most ardent one, believing among other things that it had cured his dyslexia. In public during those early years, however, when asked about Scientology, he generally went no further than admitting his membership and rarely volunteered more. As he rose to the top of Hollywood’s A-list, his public statements and appearances were carefully supervised by the queen of showbiz PR Pat Kingsley, who kept the star’s unorthodox religious practices on the back burner.

For a while, Miscavige’s hopes for a Cruise Effect on Scientology seemed well placed. The actor’s Scientology honeymoon years were for him a time of unlimited superstardom and acclaim, and for the Church its most vigorous period of growth. Membership figures are not available for the secretive organization (Church claims have varied from 8 to 20 million), but by all accounts, the Church dramatically expanded in the nineties, opening new recruitment centers around the world. The period also saw Scientology’s brand awareness take off thanks to a carrot-and-stick PR campaign. On the one hand, a retinue of star-parishioners led by Cruise (and including John Travolta, Kirstie Alley, and Jenna Elfman) put a glamorous and likable face on the Church. On the other, a program of active discouragement — through lawsuits, harassment, and, some have alleged, physical intimidation — quashed almost any negative scrutiny of the organization.

Considering the organization’s size and growing profile, media scrutiny was sporadic. In 1990, the Los Angeles Times ran a six-part series on the Church, the first major investigation of the post-Hubbard era. One article on recruitment listed ten celebrity members of the Church but makes no reference to Cruise, who was at that time supposedly still in his early indoctrination. The reporters who worked on that series later claimed serial harassment by the Church, including, one alleges, the murder of his family dog. In 1996, a Spy magazine reporter secretly joined the Church for an article and published the first account of its indoctrination procedures. A 1991 Time magazine cover story outlined the Church’s finances, calling it a “global scam.” In response, the Church sued Time Warner, seeking $416 million in libel damages. The suit was dismissed five years later, but Time Warner spent a reported $3.7 million defending itself. For the next decade and a half, fear of similar campaigns and lawsuits by the Church — which was fast becoming infamous for its litigious tendencies — dissuaded many editors from going near the topic. Throughout the period, the Church floated untouched through the public space, seen as slightly odd, but no stranger than Est, Bikram yoga, or any of the quasi-spiritual fads to emerge from Hollywood.

But then the Church pushed Cruise harder. According to Reitman, after the actor’s marriage to Nicole Kidman, Miscavige became frustrated by her indifference to Scientology. During the two-year period when the couple was under virtual lockdown in England on the set of Stanley Kubrick’s 1999 film Eyes Wide Shut, Miscavige was annoyed by his distance from the Church, both physically and emotionally. In response, Miscavige is rumored within the Church to have engineered the couple’s divorce, using the Church’s hold on Cruise to pry him away. More damaging still, Miscavige reportedly masterminded Cruise’s dismissal of his longtime publicist, the legendary Pat Kingsley, in favor of someone more responsive to Scientology’s demands — Church member and Cruise sister LeAnne DeVette.

The result was the first true debacle of Cruise’s heretofore charmed career. The 2005 press tour for War of the Worlds turned into a full-scale disaster, culminating in the mother of all unfortunate photo ops, the Oprah couch-jumping incident in which Cruise declared his love for Katie Holmes. And with Kingsley pushed aside, Cruise’s reticence to serve as Scientology’s front man disappeared. Soon he spent interviews not only praising the Church but speaking up for many of its controversial causes, at one point lambasting Brooke Shields for stating that she had taken anti-depressant medication to help her through her post-partum depression; asserting, as claimed by Scientology doctrine, that it was “irresponsible” of her to credit the drug.

The public response turned from horror to hilarity. Cruise received the worst press of his career and quickly became a punch line. Even Steven Spielberg was reportedly peeved with the actor for botching the roll-out of WotW. The fallout also spread to the Church, which received its first wave of full-blown negative attention. Reports dripped out about the Scientology tent Cruise had ordered erected on the War set, offering literature and “assists” (massages) to the crew. In that Today show interview, when host Matt Lauer grilled Cruise on his anti-psychology campaign, Cruise’s angry responses (“Matt, Matt, you don’t even — you’re glib”), delivered in his trademark seething intensity, no longer came off as sexy but as unhinged.

With Cruise so openly spouting the Church’s most controversial teachings, there was now a very public face to the tales of Scientology weirdness. It was more than a religion story now, it was an entertainment story, which will always be more fascinating to the general public. And ever more powerfully, it was a gossip story, with his hyperexuberant pronouncements of unending love to his brand-new (and sixteen-years-younger) paramour, Holmes. Her own glazed, robotic reciprocations only fed into the delicious theory that Scientology was a cult, and she was a prisoner. Gossip and news sites alike began probing into Scientology, and one PR disaster soon followed another. With Scientology under attack, outspoken critics were finally listened to, while others were emboldened to come forward, a faction that soon included the Church’s second and third-ranking staffers, who left the Church in 2004 and 2007, respectively. The growing ranks of defectors, speaking openly and now finally being heard, lifted the veil of fear under which former Church members had lived. South Park devoted a 2005 episode to mockingly laying out Scientology’s beliefs, laying it bare as a system out of a bad sci-fi novel.

Worse was to come. Someone posted a Church-produced video of Cruise manically discussing Scientology, and when the Church tried to take it down in 2008, the hacker group Anonymous declared war and has regularly delivered embarrassments since. In 2009, a St. Petersburg Times series alleged, among other things, a pattern of physical abuse by Miscavige against his staff, a ruthless pressure campaign on the IRS to win tax-exempt status, and Church responsibility for the death of a wayward member after he was held in a hotel room for seventeen days. Finally, the media elite jumped aboard after a 2011 New Yorker article detailed Academy Award–winning writer-director Paul Haggis’s Scientology journey and his decision to leave its fold.

And now, Tom and Katie’s divorce.

From the start of the couple’s romance, which seemed to begin as organically as a hostile takeover, there has spread a conventional wisdom that there was something not right about the pairing. There was open speculation that this was an arranged or unreal marriage, with widespread theories that poor Katie Holmes had somehow been bribed or coerced or brainwashed into going along with it. The now-rampant distrust of Scientology colored the portrayals of the relationship to an extent never reached with the Cruise-Kidman marriage. Yes, there had been gossip about that pairing, but not to a statistically greater degree than the average snickering about Hollywood marriages whispered to be a sham. TomKat vaulted over the norm to become a much larger and more nefarious conspiracy tale.

With the table thus set, the divorce became the perfect fairy-tale ending to the the narrative: a deluded Princess falls in with dark forces, is held hostage in her gilded cage, and then, after carefully planning her escape, makes a break for freedom — if not to save herself, then for the sake of her daughter. Whatever truth or falsity there is to this version (and that is hard to sort out amid the tabloid reports), the Grimm tale is how the divorce is being portrayed, and the press has gone all out to paint the group she fled in the most villainous terms.

While Scientology was a subplot in the Cruise-Kidman split, it is the central story line to the TomKat story. So much so that a blanket denial by Cruise attorney Bert Fields was issued, in which he declared that “The Church of Scientology played absolutely NO ROLE in the divorce settlement talks at all. Period.” At the end of this, whatever truth may emerge, the damage has been done. It will be a very long time before anyone on the outside sees Scientology as just another harmless fad celebrity preoccupation again. And the irony is that Tom Cruise, the Golden Boy who was supposed to be the Church’s game-changer, the friendly face of Scientology, is now perceveived by many to be either a brainwashed dupe or a controlling Church henchman.

With exits mounting, and for instance, the Church’s entire Israeli chapter declaring its defection, it is now an open question as to whether Scientology will survive the current crisis. If this does prove to be the beginning of the end, history will record that the Church’s biggest catch ended up sinking its ship.