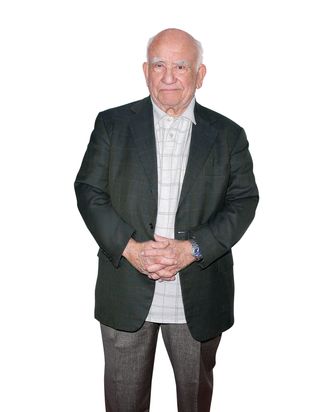

If he isn’t a star now, he’ll certainly be one within the year,” Ed Asner jokes of his current co-star Michael Shannon. “And Paul Rudd? Brilliant guy.” The two of them are still at the theater, hammering things out, or just possibly too pooped to tag along. Meanwhile he, Ed Asner, 82 years old, sits at the “Al Pacino table” at Joe Allen over eggs and lox and a double vodka as midnight approaches. Can these younger men keep up? No, they cannot. But, he tells me proudly, it’s by design: “When I come up against a strong actor, it’s the biggest fucking goad to get me to start running double-time, just so he doesn’t pass me up.”

It’s a strategy that’s worked throughout his six-decade career, during which he’s won seven Emmys and five Golden Globes as a larger-than-life, frequently scene-stealing performer. His depiction of Carl Fredericksen in Pixar’s Up led to calls for a new category of Academy Award, “Best Vocal Acting,” and has already more or less implanted itself in the cartoonish American dreamscape as the eternal icon of “Grandpa.” In real life, he maintains the sitcom timing and deadpan delivery of his breakthrough role as Lou Grant, the cantankerous editor and indefatigable Mary foil, on The Mary Tyler Moore Show: “Mary, I don’t want you to take this wrong, but you’re a jerk.”

In fact, he’s so good it’s sometimes hard to tell if he’s joking. Is he joking? He’s gracious to autograph hunters, lobs zingers to bartenders, and looks not unlike Santa Claus, whom he’s played for Ellen DeGeneres. But he says his favorite food is “human flesh, lightly peppered,” which he’s never had but might try in “oh, maybe an hour from now.” And when a young actress approaches him about a mutual acquaintance, he bellows, “Well, tell her you ran into me and I said, ‘Go fuck herself.’ ” (“Oh, really? In a sweet, joking way?”)

“Want me to bench-press you?” he asks at one point.

“How does that work?”

“I don’t know. I’ve never really lifted a human in that fashion. But it stands to reason that I will have to grab you in the most accessible places to be able to do my lift. So I don’t want to hear any objections to that.”

“Oh, shit,” exclaims his publicist, readying himself to jump in.

Needless to say, the night is not over for Asner. Never mind those other “brilliant bozos” from Grace, the darkly comic (or is it comically tragic?) Broadway play that opens this week and stars Rudd as a young, married Evangelist trying to open a chain of Gospel-themed motels (“Crossroads Inns?” “The New Restament?”), Shannon as his damaged rocket-scientist neighbor, and Asner as their exterminator whose World War II history tells him that there isn’t a God but whose recent experience implies that—no, wait—maybe there is.

As for himself, Asner’s not much for religion these days. “I tend to think that religion has probably killed more people than anything else,” he says, though by growing up as an Orthodox Jewish kid in Kansas, “I was blessed, because a little discrimination does a lot to give you character.” So does working on the assembly line for General Motors, which Asner did before getting called up for the Korean War. “We realized that we wouldn’t be part of the glory of World War II, but we’d be part of the goddamned draft system. When they finally sent me overseas to France—not Korea!—my job was typing up the training schedule on a stencil.” Two weeks before coming home, he got a letter from Paul Sills, whom he’d met before dropping out of the University of Chicago. “He said, ‘We’re starting a theater company. Come join us. We’re doing old plays and new plays.’ ” Asner returned home to do just that, performing with the crew that would one day become Second City. He slept at the theater in his “own little cubicle” and worked in a bundling factory between shows. In 1955, he moved to New York, “had a lot of smoke blown up my ass, and then leapt to California.” His first night at his apartment in L.A., he was working his way through a TV dinner and watching Jackie Gleason for the first time when he heard a commotion and went outside to find two raccoons lying on their backs and eating avocados from his tree. “I said, ‘This is for me.’ ”

Few actors have had the iconic status and longevity that Asner has enjoyed. And few have been as politically active, motivated as Asner was by his days as a “sad sack” working in a “goddamned slave factory.” He served two terms as the president of the Screen Actors Guild and has been an outspoken advocate of socialism, though now, he says, he’s not even sure what that means. “Politics used to be a very compelling drive for me, but I’ve given up. It’s over for the American empire. But like many empires, it’ll totter and weave for a long time before anybody really puts the kibosh on it.”

He finishes the last bite of banana-cream pie. “That means I didn’t do you a bad turn,” the pretty waitress says, whisking the plate away.

Asner half-grins. “You will.”

*This article originally appeared in the October 8, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.