“It’s quite something to have one of these in your mouth, isn’t it?” Ewan McGregor says, mumbling a bit, because of the greasy chicken foot poking out from between his lips. Moments before, in the old-school, linoleum-filled Chinatown diner Nom Wah, he’d proposed that we “order the most extreme Chinese thing here.” The chicken feet had seemed like a good idea. Now, we’re not so sure.

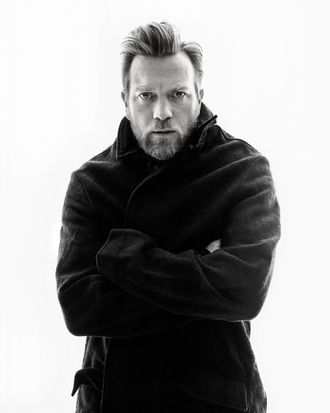

“It’s just … fat,” says the actor, wearing a black corded cashmere sweater under a weathered motorcycle jacket. He’s dashingly handsome despite the slimy foot that he’s turning around in his mouth like a cigarillo. “Fat and cartilage. Lovely!”

McGregor, 41, pulls out his phone and snaps a picture for Eve, his wife of seventeen years and mother of their four daughters, noting that though she’s French, she grew up in Beijing. Behind him, a young girl surreptitiously snaps a photo of the actor with her camera before building up the courage to come over, giggling: “Obi Wan!” He still gets this a lot, and though he swears he doesn’t read his own press, he does have a fairly accurate sense of his lingering reputation. “I’m the naked, nondrinking guy, from a galaxy far, far away: That’s me.”

Of course, it’s been twelve years since McGregor swore off alcohol and seven since he appeared in a Star Wars movie. “And I haven’t taken my clothes off on film in years,” he says. “Not that I won’t do it again, but it almost sounds like I flash the journalist sometimes.”

He does not unsheathe his light saber in my presence or in his new film The Impossible, opening next month. Nevertheless, the intensity of the movie, a wrenchingly realistic depiction of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, has been making audience members faint for very different reasons, from the Toronto Film Festival (where a film producer collapsed a few seats away from me) to Spain, where the film has smashed box-office records. “We went to dinner across the street from a screening in San Sebastián and watched three ambulances pull up by the window of the restaurant,” he says. “It’s fantastic.”

Director Juan Antonio Bayona (The Orphanage) deployed thundering water tanks to dramatize the terrifying ordeal of one Spanish family—father, mother (Naomi Watts), three young sons—separated by the catastrophe, struggling to reunite. Causing minor controversy, Bayona cast McGregor and Naomi Watts in the lead roles to go for English-language appeal. “I sent Ewan a note saying that I would love to have worked with Gregory Peck or Spencer Tracy, but unfortunately I can’t do that, so I’d be happy to work with you,” says Bayona. “I wanted an Everyman.”

On its face, the idea of Ewan McGregor, Everyman, doesn’t make much sense, since he’s both astonishingly good-looking and has made his name with wild gambits: the tweaked-out blitzkrieg of Trainspotting, the glam-rock insanity of Velvet Goldmine, the gruff sexuality of Young Adam, the breathless romanticism of Moulin Rouge! Most Everymen earn their reputations by playing the same guy in different situations, but McGregor has taken another route, playing so many different roles in so many films—40-plus movies in eighteen years—that if anything he’s earned Everyman status by trying, literally, to play every man.

Despite his comprehensiveness, McGregor has rarely played a parent. “The Impossible is not the first time I’ve played a dad, if you include my epic and award-winning performance in Nanny McPhee Returns,” he says. “But it’s certainly the first one I’ve done that explores parenthood.” McGregor says he tries not to ever draw on his own children for inspiration (“That would feel manipulative”), but his shell-shocked father feels desperately real, stoic except for one brief powerful scene, in which the actor, surrounded by actual victims of the tsunami that Bayona called onto the set, completely falls apart. “Honestly, [inviting the victims] seemed a little gimmicky to me,” says McGregor, who notes they were surrounded by survivors every day while shooting in Thailand. “You can just react to the scene.”

I tell McGregor that his creative restlessness makes it hard for one to discern much of a pattern to his career—and he says he thinks less of his parts than where he’s lived: Scotland when he was younger and struggling, then London for years as his profile grew, and now L.A., which he admits is starting to creep him out. “You feel yourself become aware of where you are in the business,” he says. “In London, New York, or Paris, I’ve never felt like that. But suddenly, in L.A., you think of yourself on this big list, and you’re down here. It’s a horrible way to be.”

He’ll follow The Impossible with Jack the Giant Killer in March, but he says, “This is the least work I’ve ever done in my life, since I was 20 or 21, because of HBO and The Corrections.” HBO rejected the pilot for the Jonathan Franzen adaptation directed by Noah Baumbach last May. “At first I was sad, but when I saw the pilot I was devastated,” he says, noting that he’d expected to devote four or five years to the series. “Creatively, I was destroyed because it was so powerful.”

As we leave the restaurant and stroll through Chinatown, McGregor says he enjoyed his time off in Scotland and France, catching up with family, running (with Muse as his soundtrack), and reading novels like Michel Houellebecq’s Platform, a recent favorite. Now, he’s back on track. He recently wrapped August: Osage County in Oklahoma, co-starring Meryl Streep and Julia Roberts, and has several other films queued up, including one with Wim Wenders.

We’ve made our way to “The Museum,” an art installation curated inside a tiny Chinatown freight elevator. The walls are lined with misfit items from all over the world: strange weapons, obscure toothpastes, counterfeit Sharpie pens. “Oh! That’s a big plastic glove for reaching up a cow’s bum!” McGregor says, pointing at a transparent, shoulder-length glove. McGregor, a travel addict who motorcycled 19,000 miles for his documentary series Long Way Round, has a story to match most every piece on display. The glove triggers a gross tale about a Scottish farmer pal who extracted calves with chains and a winch. A printed list of methods for controlling chronic masturbation draws his skepticism: “In severe cases, it may be necessary to tie a hand to the bed,” he reads aloud. “What? Once you tie yourself up to the bed, that’s when you start to feel really horny!” His favorite items are the vintage, Communist-era watches, whose dials have been altered by hand. “I like that they are a way of putting your own little stamp, your identity,” he says, “into a system where you can’t really freely express yourself.”

That’s not a bad metaphor for acting in Hollywood, but McGregor offers a better one minutes later, when he’s discussing his recent hobby of building bicycles. “You buy a frame on eBay, and you think, What do I do now? You have your aesthetic idea, but all bike builders say it kind of builds itself—which it does in a way. Things either do or don’t work. Components fit or they don’t, and sometimes you alter them until they do. At the end of the day, you’ve built a work of art, but you can also ride it to the shops.” Only, he adds, “nobody rides bikes in L.A.”

*This article originally appeared in the December 3, 2012 issue of New York Magazine.