“FYI: There. Is. No. New. Novel. Being. Written. Except for maybe The James Deen Story and something called ‘Come over at do bring coke now.’ ”

That’s a tweet from Bret Easton Ellis, a thing that, as an entity unto itself, may have less valence than most molecules in the universe. And yet it’s a well-crafted almost-sentence, a 140-character snip (complete with missing words) of Beat poetry, which flows out of Ellis in an endless roll. These days, instead of writing books—as he says, he isn’t working on a novel now, or even notes for one—he can stir up trouble with just a flick at his keyboard. It takes him “30 seconds to one minute,” or so he claims, to beam out pop-cultural observations, L.A. vignettes, and world-weary little outbursts, sometimes featuring his boyfriend (“the 26-year-old”) to a respectable 340,000 followers and the media at large, which often picks them up as gossip items. “I just have these random thoughts, go to bed, and then next day it’s sort of world news,” Ellis says, waving a hand.

Twitter mixes literature (of an admittedly minimal sort) with performance, and it’s perfect for Ellis, who has always been, when you think about it, more of a conceptual artist than an author. The work isn’t beside the point, but it isn’t the whole point. In this new métier, each part of his persona is on view: satirist, nihilist, glamour guy, exhibitionist, knee-jerk contrarian, self-pitying cokehead, and a few other things, all of which make some laugh with glee and others avert their eyes in boredom, and even more glance back in spite of their revulsion, wondering, as one of his followers did the other day: “Is Bret Easton Ellis dead inside?” Indeed, on Twitter, just as it was with Less Than Zero almost 30 years ago, that’s still the question. It may or may not be a question he asks himself—that, too, is part of the show. Ellis has worked hard to make himself a pop-cultural monster—“monster” has been one of his nicknames—then denies that he’s anything but a middle-aged homebody.

Anyway, a quick refresher on the particulars of his tweet: James Deen is the porn star he’s cast alongside Lindsay Lohan in the new movie The Canyons, catching them both in a typical Ellis low-culture embrace. (Ellis has long been in touch with Deen’s talents through the “many private porn sites that I am a member of,” he says). Lohan, in her decline, is basically an Ellis character, like she sprang from his mind, and The Canyons is a dark, soapy thriller with a great tagline—“It’s not the Hills … ”—and production values that are actually much higher than the ones in the trailers playing on various gossip sites on the web. There’s a love hexagon among twentysomethings in L.A. who are bored by each other, bored by the Chateau Marmont, bored by sex, even with hired third parties—in other words, not a deviation from his other work. Ellis was a bit offended by The New York Times Magazine cover story about the film, which said that he didn’t like the final product. “That was wrong, as was the fact that we were a bunch of losers trying to get our careers on track,” he says, referring to himself and Paul Schrader, the director of the movie.

Ellis clears his throat. “Ohhh-kay,” he says, gearing up to discuss the Deen-and-coke tweet. “It was Saturday night.” His boyfriend, Todd Michael Schultz, an impish composer and loose-leaf-tea blogger, was in Calabasas, “doing his music thing with his collective or whatever. So I decided to watch the Rolling Stones documentary Crossfire Hurricane, which is not really that good, you know; it’s okay. I knew all of this shit already. But there were a couple of shots of people doing coke off plates in ’72 on the Exile on Main Street tour, and I was thinking, That looks pretty good. That looks pretty good.”

Ellis drinks prodigiously, usually a top-shelf and very clean tequila or gin cocktail, or a nice white wine, like a housewife (he allows that he may be a “functioning addict”). Cocaine isn’t part of his life anymore, at least not most of the time.

But Saturday evening, while he was watching the film, he drank some tequila, took some Xanax, and then wanted some coke. The only dealer he could think of to call was a guy who came to L.A. to be an actor, “but that didn’t work out, so then you’re a real-estate agent, gay for pay, or a drug dealer,” Ellis says, adding that this particular guy somehow ended up selling a script to a famous movie star and getting signed by CAA, so now he’s a big shot, not a dealer.

And what other coke dealer did Ellis know that he could call in the middle of the night without embarrassing himself? He couldn’t remember. And then he passed out from the Xanax. But just before he lost consciousness, at 3:44 a.m., he posted a tweet that read, “Come over at do bring coke now.”

“Boring,” I say.

“It’s the truth!” he half shouts. “I was basically half-asleep. There was no coke.” Anyway, he doesn’t seem embarrassed. It’s grist for the mill.

Ellis likes to say that the myths about L.A. are wrong, that it’s less a city of reinvention than a place where you become yourself, and he’s correct in this regard. As many actresses as have moved from Iowa and taken new names, and as delightful as it is to live in a place where no one asks about your alma mater or tries to pinpoint your family’s financial status, it’s a lonely place: There are few public spaces in the city other than hiking trails, and the distances between the most mundane activities, often spent on apocalyptic freeways, loom large in the mind. Most important, given the difficulty of making it in Hollywood in any way other than through social connections, the concern of most of those you meet is not collegiality or lasting friendship but what you can do for me, whom you can introduce me to. You find yourself staying home more often than not.

In many ways, it’s a perfect city for Ellis, who likes both the pop-culture swirl and standing at arm’s length from it. Lohan and Deen—these are not the people leading the culture, like Lena Dunham and Frank Ocean. But they are part of trash culture, the stuff that is like dust on the surfaces of our lives, whether we admit it or not. Ellis has always been obsessed with surfaces, the superficial details that we use to define ourselves, and each other: black-slash-beige strapless Navajo dresses, herb-mint moisturizer, and types of baby-shrimp-tempura rolls. “We’ll slide down the surface of things,” hums Glamorama’s Victor Ward, the “full frontal gorgeous” “It” boy, as he navigates the nineties New York world of Industria, Marlboro Mediums, Radu, and Frederique. “Reflection is useless, the world is senseless,” says Patrick Bateman in American Psycho. “Surface, surface, surface was all that anyone found meaning in.”

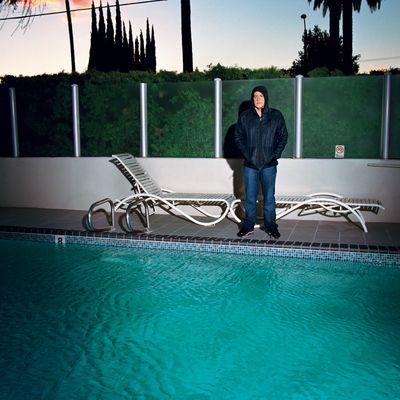

That’s still, to a large extent, Ellis’s obsession. Sitting in his almost pathologically plain gray office, a Red Bull and a green prescription bottle of Schultz’s medical marijuana in front of him, along with a lighter with lettering that reads MEDICATE WITH THE BEST, he wears thick glasses, and his hair is dyed sundown-orange to cover up his gray. He’s six feet, but seems larger, with a sweet, pleading cast to his eyes and a giant chin, as well as a friendly manner, stumbling over his words more than one would expect and raising his voice to an enthusiastic shriek when he makes a funny point. He wears Asics sneakers, a Lacoste shirt, a windbreaker, and jeans. “This is my uniform,” he says. “I used to wear sweatpants, but people told me to stop wearing gym clothes around town; it was like that Seinfeld line about how you’ve given up on life when all you wear is sweatpants.”

Much like post–World War II Case Study Houses, the condo he lives in is like being in a bubble suspended over the city, watching the weather drift by. It still has the furniture from when it was a model apartment. The sun attacks through sliding glass walls with a classic view of Los Angeles, angled southwest from the elegant spires of downtown to the Pacific’s horizon line. In his office, he turns on a small light directly above him, which makes it look like a surgeon is about to drill into the top of his head. Ellis spends most of his time here, leaving for meetings, to work out with his trainer, to shop at the gourmet grocery store Bristol Farms, and to take in a matinée at the ArcLight movie theater. Dinner is at Soho House or the Chateau Marmont. “That’s about it,” he says. “That’s all I do. This is a really depressing conversation.”

The perch does have its benefits: From here, in front of a massive Mac computer screen, it’s easy to maintain the Ellis mystique through Twitter, that most malleable medium and the main way he keeps in touch with culture these days. We’re living in a less glamorous era than the eighties and nineties, with our locavores, street-fashion bloggers, and BuzzFeed, but he’s also 48, too old to be going out with young people every night, picking up their conversational static. Ellis is planning a new production company and writing for TV and movies—a prep-schoolers turned monsters show for Gossip Girl creator Josh Schwartz and an espionage show set in the nineties are on the docket. Ever since he was a boy, he’s dreamed of the day that he could go to a movie theater and something he wrote—and not just based on something he wrote—would be on the screen.

So, Twitter: That’s a way for him to see what’s happening and, of course, be seen, too. There, he writes things that are gossipy—when he spied an unhappy Kirsten Dunst, he exclaimed, “[she] looked a lot sadder when I ran out of coke at an Oscar party 5 years ago”; intelligent—“the fallacy of the theory that TV is better than the best movies is that people believe that WRITING is EVERYTHING when in fact it isn’t”; stupid—“Jodie Foster was drunk,” he said, rejecting her recent speech at the Golden Globes out of hand; and defiantly, nastily un-p.c.—after Paris Hilton was caught on audiotape saying that gay guys on Grindr are “the horniest people in the world” and “most of them probably have AIDS,” he tweeted, “As someone who has used Grindr? Paris Hilton isn’t that far off.” He also said that “Kathryn Bigelow would be considered a mildly interesting filmmaker if she was a man, but since she’s a very hot woman she’s really overrated.” He wrote a mea culpa to that one, but “everyone thought what I wrote was a load of shit, so whatever.” He sighs. “I hate being called a shit-stirrer and a provocateur, because I don’t believe I am,” he says. “I tweet what I want to tweet.”

Is that true, or does he not believe anything he’s tweeting? It’s the same trick that made Ellis famous: He seems so noir and Chandleresque in his utterances, like a black hole—is he dead inside?—and then is laughing the next minute, letting you in on the charade. You can never tell how much is a put-on, and that’s part of what makes him, and his books, and now his tweets, spooky: Just who is throwing these bombs? Twenty-one years after the publication of American Psycho, which has turned out, in a career in which most of the best work was done in his twenties, to be his masterpiece, I still feel uncomfortable calling it a satire. On one hand, it must be, since it’s about a Wall Street killer who is an actual killer, with deadpan chapter titles like “Killing Child at Zoo,” “Tries to Cook and Eat Girl,” and “Taking an Uzi to the Gym.” On the other, some of the events are so graphic, so disturbing, so evil—rats eating cheese out of vaginas and women getting nail-gunned to the wall—that I haven’t read most of them to the end, less found the humor. Rereading his books now after worshipping them in high school, I’m struck by how boring they can be, and how much that boredom is part of what Ellis is trying to elicit.

Ellis came close to writing a memoir with Lunar Park, a horror story in which Bret Easton Ellis fathers a child with a famous actress and is followed by the paparazzi to a friend’s villa in Nice, but he decided to fictionalize it. A real memoir would be “the ultimate narcissistic con job.” He smiles. “I’m not writing a memoir,” he says. “Don’t make me barf.”

“Each book comes from a place. A place of pain or confusion,” says Ellis.

Ellis grew up “over the hill” in L.A., as those in the chic neighborhoods of Beverly Hills and Bel-Air call the Valley, the eldest of three in an upper-middle-class family concerned with appearances, even by the standards of the city. Ellis went to Buckley, one of the city’s traditional private schools, with uniforms and regulations on hair length, and adopted the ironic and aloof pose of the New Wave. Ellis kept journals about going out with friends, then embellished them to keep himself entertained. “I’d write down that we went to the Psychedelic Furs at the Whiskey, and then add what would have happened if we went into an alley,” he says. There were drugs: He played in a band called Line One, and when I ask if that’s a reference to a telephone line, he shakes his head and inhales noisily.

Behind the doors at home, though, everything was not well. Ellis’s father, a real-estate investment analyst, was physically abusive to him and his mother, though his father spared his daughters. “My dad was a big guy—I’m a big guy, too, but he was a bigger guy,” says Ellis. The depiction of gender dynamics in his books, with sadistic males and promiscuous, passive women, goes back to his parents’ relationship. “That did create—I have to cop to it now—a vision of female-male relationships mostly like theirs, until I got to a certain age and people told me, ‘No, they’re mostly not like that,’ ” he says.

Bennington was a way to escape his dad, who died at 49. Ellis had girlfriends during the first two years of college, though he was also with men. In public, he’s called himself “bisexual,” like his male characters, who are not limited by gender in choosing their partners, and when I ask him to say he’s gay on the record, he says, “You want to know something? No. Not in the context of what gay means in this culture, where Eric Stonestreet can win an Emmy for playing the most stereotypical queen on TV … and gay people can’t make gay jokes and have to like Modern Family.”

It’s incredible to think that Ellis published Less Than Zero at 21, and then American Psycho at 26. At that tender age, he captured the culture twice. He nailed the eighties at a time when he probably still didn’t understand it, and those two books, not Tom Wolfe’s or Jay McInerney’s, will be the ones remembered. American Psycho was dropped by its original publisher, and nearly everyone hated it—conservatives, feminists, the high-culture elite. “When not a single newspaper is on your side, and everyone is writing terrible editorials about how evil you are, and USA Today is running an illustration of you with a cape and claws, it affects you,” he says.

But in New York, he couldn’t have been more of a star, even if he was a bit odd. Every holiday season, he would throw a huge Christmas party at his Union Square loft, but before everyone came over, he removed every stick of furniture, including his bed, keeping just a few things, like one Paul Smith black suit (he only ever wore black suits). He also hired a “team” of 35: caterers, eight bartenders, a sound-system guy, and “two security guys with earphones—ridiculous—who would stand downstairs with the doorman and contact the ‘team’ if someone showed up uninvited, and I’d be asked if I wanted to let that person in,” he says. “I always let everyone in. I loved the party scene in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and I thought if you’re going to have a party, make it packed and fun.”

Though everything went perfectly, except “the line for the bathroom was always too long, because multiple people went in each time, and were not using the bathroom for the purpose for which it was built,” Ellis would slip out by eleven for Mary Lou’s, a West Village after-hours bar with blood-red walls where gangsters, socialites, and publishing executives (it was once a glamorous industry) gathered at tables with pristine white tablecloths, also taking too many trips to the bathroom. Then he checked into the Mercer Hotel. When he returned home a couple of days later, his apartment would have been put back just as it had been.

Ellis smiles wanly. “My youthful extravagance,” he says. “I am kind of embarrassed by it.”

The tweets are great and self-revealing, but when I ask Ellis why he doesn’t write essays, he looks at me with fear in his eyes and says, “I’m not smart enough.” There’s part of him that is insecure, hurt—when he talks about his dad hitting him, he raises a fist in the air, and it hangs there for a while. He also becomes quiet when we talk about what happened after his Christmas party in 2003: He’d gone to the Mercer with his partner, a sculptor, at a time they were having some trouble—“Yes, I’m Bret Easton Ellis and there was a lot of soul-searching going on at the Mercer hotel,” says Ellis, grimacing—then flew to L.A. for the holidays. While he was there, his boyfriend died of an aneurysm, bags of groceries that he planned to put away still in his hands. Ellis didn’t return to New York for a year and a half, and has not lived in the city again.

So is he dead inside? He’s not a ghoulish madman laughing at the computer keys. In a life with some pain, he likes not feeling. There is some dead inside there. He likes raging, and then numbness. The numbness of his prose mirrors the way he likes to feel. Xanax is his drug, after all. When Ellis complained about David Foster Wallace on Twitter, about his AA moments and lightbulb thoughts about what writing should be, he called him the most “tedious, overrated, tortured, pretentious writer of my generation,” and “the best example of a contemporary male writer lusting for a kind of awful greatness he simply wasn’t able to achieve.” It makes one wonder how he feels about greatness. “Yes, I’m mad—or I’d say frustrated—that whatever Wallace and Dave Eggers were doing beat out the thing I, and my peers, were doing: a cold, brittle, scalding view of the world, pissed off about everything,” says Ellis. “Those tweets aren’t angry, even though they read that way. It’s more a lament that there seem not to be both [styles] anymore.”

On a Friday afternoon, a housekeeper is making Ellis’s apartment as antiseptic as Bateman would demand; the only personal touch in the living room is an old Life magazine with a picture of Jesus. “Todd is going through a spiritual phase,” says Ellis, pursing his lips. He likes dating young guys—as one of his characters says, they “keep everything on the surface, even with the knowledge that the surface fades and can’t be held together forever.” But things haven’t been going well with Schultz. “I find myself telling him that his ideas aren’t going to happen,” says Ellis. “And I don’t want to be an authority figure or a Debbie Downer.” Earlier, he says, “I’m like … arrested development! Some people think the moment you become famous is the age you stay forever. Now part of me doesn’t believe that. But I have friends who would say, ‘Bret never grew up. He got frozen in that space in time, between Less Than Zero and American Psycho, back when a novelist could have that kind of fame in the world.’ ”

As Schultz scurries up from the lobby after collecting signatures to get on the ballot for city councilman, Ellis heads to the garage. The Hollywood journalist Nikki Finke lives here, as the world knows because he tweeted it, and then she threatened to sue him and write nasty things about ICM. That didn’t happen, but she complained to the building’s owners. “I had to go to the building manager’s office,” says Ellis. “He read off a list of the people who work here: ‘Did Garcia Rafael Espana tell you that Miss Nikki Finke lives in the building?’ I said, ‘No.’ ‘Did Shania tell you … did Patricia Ortega Lopez tell you … ’ ”

He opens the door to a black BMW 528i, the “ubiquitous L.A. dude car,” as he calls it. The Beverly Hills shopping promenades on Rodeo and Canon Drive roll by before he veers into Century City, where forbidding skyscrapers housing white-shoe law firms and agencies like CAA and UTA rise from streets with so many lanes they’re like autobahns, then pulls into a subterranean garage for the Westfield Mall. He needs to go to Bloomingdale’s for some moisturizer. “Men who go under the knife look like—you know the joke—the Village lesbians,” he says. “But growing up in L.A., I’ve known about fillers and stuff since I was 10. Fillers are great. But my secret is moisturize, moisturize, moisturize. Growing up in a home where my parents were narcissists and the kids had to look perfect, I always moisturized. I had one of my high school’s first subscriptions to GQ.”

Ellis ascends an escalator pointed toward daylight. We talk about what he would have done if he weren’t a writer. “I love talking to my trainer,” he says. “And we were talking about how we fantasize a lot about James Deen’s life—he has a girlfriend, a sexual libertine, and he’s addicted to pornography.” Deen shoots one porn scene a day most of the year. “Is that great, or would it be awful? Anyway, that’s what I would do. Either writer, musician, or porn star. Really.”

And then we’re sauntering down the well-proportioned corridors of the mall at the same lugubrious tempo as everyone else, and he’s talking about the Microsoft swag event in Venice last week, and he’s saying “it’s crazy it’s so nice out—it’s the winter.” And he buys some noise-canceling Bose headphones that he selects from under a blue sign with white lettering that reads GIVE THEM WHAT THEY REALLY WANT and we go into the Mac store to get him an iPhone case and he looks at them but thinks they’re too expensive and he gets flustered and says “it’s so fucking annoying” but buys one anyway. And we’re back outside waiting for a coffee and people are buying Christmas cards and he’s talking about the Gus Van Sant premiere that he walked out of last night because he likes to sit in a particular place in the theater and he was nowhere near that place.

In a lot of ways, it’s more Ellis’s world than ever, as if he had invented it. Certainly, no one else would have thought to describe it. I ask him, “Do you like it here? Or does this fill you with dread?” And he nods and says, “I like it here. Definitely. I find this mildly pleasant.”

*This article originally appeared in the January 28, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.