Even the sharpest literary satirist of his generation can’t afford to ignore Valentine’s Day, especially if his wife is turning 45 the next day. And so Sam Lipsyte, whose last narrator disdained the “rom-com pone” of, say, Nora Ephron, with its “coffee bars and turtlenecks, all that greeting-card ontology,” finds himself in the cramped aisles of Duane Reade on February 14, searching for a card earnest enough to be gifted ironically. “We may have to go to Rite-Aid,” he says, sighing.

“The serious ones are the funniest ones,” he declares, after crossing the street into our second fluorescent-lit pharmacy. Encroaching mortality pressures many urbanites into marathons and egg whites, but at 44, Lipsyte seems to have shuffled contentedly into what once looked like premature middle age. Bearish and bearded, swaddled in zippered sweaters, crowned with the barest wisps of black hair, he comes across as both a rumpled double of his bitter-slacker alter egos and a J. Crew–ish rebuke to them.

“It’s not even that I really disagree with the sentiments—they’re not wrong,” he says, opening a layered card to reveal sunny fields and a free verse that opens “Thank you for letting me be me.” “They should get somebody like Louis C.K. to do a line,” he says.

A few awful cards later, he’s just about ready to give up. “I think I’m gonna make a card,” he says finally. His 8-year-old son and 5-year-old daughter are already planning a DIY rhinestone-and-glue session tonight, he says, and Lipsyte himself once held a menial job folding greeting cards—an operation he suspected was a drug front, mostly because his manager once offered him a bump of cocaine in lieu of a sick day. “They told me if I ever had an idea, they’d consider it,” he says. “I said that they should put some Monet painting on a card and then say ‘Monet Makes the World Go Round.’ They didn’t like it!”

Lipsyte’s second story collection, The Fun Parts, out this week, is the mid-career survey of a writer in sync with our tragicomic times—one who speaks to the acerbic nineties post-punks he once consorted with and a younger crowd with equally dismal prospects but no recourse to anything you could call “alternative” with a straight face. Lipsyte once described the French novelist Michel Houellebecq as “a cold, prickly nihilist as opposed to a warm fuzzy one.” He should know, because he’s our warm, fuzzy nihilist. He likes to quote Donald Barthelme: “What must wacky mode do? Break their hearts.”

Ten years ago, when no publisher would touch his second novel, a burly ex-punk peddling unreliable, unemployable narrators railing against “one percenters” didn’t seem to have much to offer. The anomie of Lipsyte’s generation—that is, X—was supposed to have been extinguished, first by the go-go nineties and then by irony-killing September 11, 2001 (also the publication date of his first novel, The Subject Steve).

In many ways, it has been extinguished. But several years of war and recession later, the ranks of the underdogs have swollen, and “one percenters” turned into the target of a global protest movement. Of course, that movement is more often friended or followed than truly engaged—consumed by way of grumblecore avatars like Louie’s Louie and Hannah Horvath or, in fiction, via the bleakly funny American badlands of David Foster Wallace and George Saunders, who’ve elevated willing self-debasement to the level of national pastime. These modern absurdists can be hard going, but Lipsyte never is. He’s the surest and most pleasurable navigator into this cold new world, the one whose sad-sack characters you’d actually want to meet—or mimic.

“There are little tics that he has that have spread like kudzu over the short stories of a certain kind of young writer today,” says Lorin Stein, who edited Lipsyte’s last two novels at FSG and now helms The Paris Review. Stein was in a tight circle of Lipsyte’s literary friends and remembers him as “the rabbi of Astoria,” a showman and a mentor, who once told Stein, “It’s your job to publish crazy writers.” The novelist Ben Marcus, the writer who brought Lipsyte to Columbia to teach fiction, sees “the Sam bug” everywhere—countless tales of narcissistic despair dressed up as comic social critique. “But it’s like Dylan’s voice—you can’t sing like that if you’re not Dylan,” says Marcus. “Sam’s style isn’t just some accessory that he chose for himself. It arises from who he is and what he’s gone through.

Lipsyte’s last novel, The Ask, gave us the hilariously depressing Milo Burke, the tenuously employed hero of Great Recession America—a country Lipsyte described as “some gummy coot with a pint of Mad Dog and soggy yellow eyes, just another mark for the juvenile wolves.” It also made a scruffy antihero out of Astoria, the author’s old neighborhood in post-working-class Queens. But six years ago, the former noise-rocker, who once went by the name of Sam Shit, moved his family to Morningside Heights, near Columbia, and settled in among the coffee bars and turtlenecks. On Valentine’s Day, we opt for lunch at Legend, the uptown outpost of a slightly antiseptic Chinese mini-chain—good if you stick to the Sichuan stuff. The milieu feels upscale suburban, and Lipsyte, seated at a beige banquette over kung pao shrimp, seems quite at home.

Lipsyte grew up in Closter, New Jersey, a town slightly tonier than the spiritual wasteland in his second novel, Home Land (in which Lewis “Teabag” Miner pens angry letters to his old high-school newsletter explaining “why I did not pan out”). “I knew that I should be skeptical of things long before I knew how you would believe in them,” he says. Sam’s father, Robert Lipsyte, was a sportswriter for the Times, a celebrated cynic who tilted against the profession’s reflexive hero worship. Sitting on the edge of the tub as his father shaved, Sam would ask if his dad’s famous subjects were nice. “What the fuck does it matter whether everybody is nice or not?” Robert exploded once—a reply that, Lipsyte later wrote, “cracked the world right open for me.”

The Fun Parts abounds with writer-fathers. “Don’t be a damn pansy!” one of them exhorts his son. “I’m leaving your dying hag of a mother!” The scene appears as a flashback during a brutal drug-related beating, which the now-grown son might actually be enjoying. “I’m not gonna claim he loves that story,” says Lipsyte, whose parents divorced in the eighties. But “he told me a long time ago, ‘You live by the sword, you die by the sword.’ ”

After finishing half his shrimp, Lipsyte lays down his chopsticks. “The anger is still with me, but it’s not the same kind of anger. I mean, it’s not necessarily directed outward at the world in quite the same way. That’s maybe why I decided to write in the voice of a drone,” he says of one new story. “I’m interested in all of the crazy, petty, but seemingly enormous ways that we resent the situations that we’re in and do or do not see our culpability in them; in the way that people miscommunicate; in the way that anger can serve as a mask for other things—that collision of righteous anger about drones and completely selfish anger about imagined slights at other people, the way that these things can coexist in you.”

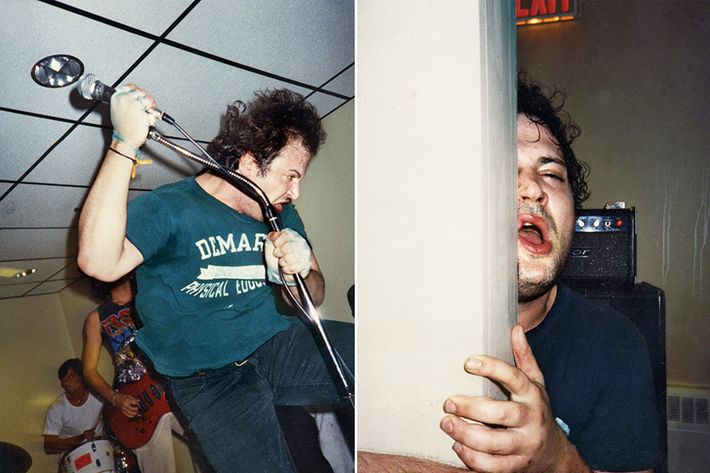

Lipsyte’s anger has proven remarkably adaptable. After graduating from Brown, where he soaked up the lessons of resident postmodernists like Robert Coover, Lipsyte and some friends moved to the Lower East Side and began indulging in the local chemicals. They also formed a noise-punk outfit, Dungbeetle, with Lipsyte as front man (or “lead screamer”). Rob Reynolds, who was their guitarist, calls the former Sam Shit “a ferocious guy—but a cross between [Motorhead’s] Lemmy Kilmister and Andy Kaufman. You could never tell if he was joking or serious.” Sam Shit’s signature move was to get down into the audience, find the hardest-looking punk, and gently run a hand across his cheek. “He was like a charismatic cult leader,” says Reynolds.

In high school, Lipsyte had won writing awards, including “a medal from Ronald Reagan for some imitation New Yorker short stories,” he says. But “I felt fraudulent, so I did other things, screamed around musicians.” And slipped, briefly, into a daily heroin habit. Dungbeetle recorded their “big” single in a loft in Dumbo, ignoring the interruptions of an ax-wielding truck driver. Their sound engineer was James Murphy, who went on to front LCD Soundsystem and now credits Dungbeetle as an early influence.

In 1994, as Dungbeetle was dissolving, Lipsyte’s mother fell ill with cancer. He’s reflected often on that crucible: quitting drugs, getting his ass kicked in a workshop by legendarily brutal editor Gordon Lish, nursing his dying mother. Incidents from those years pepper all his work, but especially his first collection, Venus Drive.“My mother dying was a huge part of being able to write those stories,” he says. “Without the mother part of it, it was just little kids in bands doing drugs. And that should be treated lightly. But the other stuff, the haunting and the death, that gives it that weight.”

These aren’t the struggles young writers bring up when spreading the Lipsyte legend. They talk about the piddling $3,000 advance he got for Venus Drive, the debut novel doomed by 9/11, and the rejection of Home Land by 30 publishers before it was put out as a paperback, after being passed around as a Word file like samizdat—or a noise-rock bootleg. “I think these things really shake out over time,” says Lipsyte. “Irony is what gets people through world wars, and as long as there are large institutions and large voices, there’s always gonna be a need for satire, a need to cut the other way at official life and to dismantle our version of propaganda. I’m probably one of the last people that still believe you can sell out.”

Lipsyte came of age during the early nineties, when misfits looked nostalgically to the punk mores of the stagnant seventies. He flirted with the web boom as an editor at Feed, a site founded by his Brown roommate, Steven Johnson. Johnson went on to become a writer-lecturer and Internet proselytizer, while Lipsyte languished in obscurity. But a decade and an economic bust later, some of those nineties attitudes—cynicism, malaise—don’t look quite so outmoded anymore, especially to the indebted, overeducated readers who make up his fan base.

“The pie has gotten smaller, and it’s harder to get aloft,” says Lipsyte. “To me, the whole idea of the loser is a joke, because it’s a kind of really oppressive society that’s calling you a loser. It’s a society that’s about celebrity and money and status and all of these things that are not very available to most people. Most people are automatically rendered losers.”

Saying this over his shrimp, Lipsyte cocks his head and turtles it forward, widening his eyes, in a way that brings home Stein’s insistence that “he’s not a frivolous dude.” For the novelist Chris Sorrentino, another of Lipsyte’s buddies, the “loser” fixation isn’t just a social statement. “He’s saying, ‘The world doesn’t really care about us as much as we might hope it does. Look how far from the center of things we actually are, how palpably unimportant our conceits or ambitions are to the cosmos.’ ”

When The Ask hit the extended best-seller list for one week, Lipsyte’s agent told him he could forever call himself a New York Times best-selling author. He describes it as a fleeting sensation. “It touched,” he says, “and then it fell.”

The best thing to do was keep moving. The Fun Parts looks past Lipsyte’s downbeat youth and the quasi-confessional humor that’s made him so appealing. Two of the stories are told from a woman’s point of view, four in the third person, and one ends with a plane, Drone Sister Reaper 5, taking aim at a character. In another, a narrator asks, “Exactly whose colostomy bag must I tongue-wash to escape this edgy voice-driven narrative?” And in the last two stories, his targets are writers—a memoirist who sounds like James Frey and an apocalypse-preaching author who sounds like Daniel Pinchbeck.

“I was trying to have fun with the notion,” Lipsyte says. “Suddenly, you’re not just someone producing work, you’re somebody who has to be a personality around that work. Nowadays, you have to be the spokesperson, the interpreter. I still have romantic notions of a time that may not have existed, when you published a book and then you disappeared somewhere, and then got a telegram about a good review.”

Lipsyte’s currently in a more reclusive mode—on leave from Columbia to start a new novel. Like all his books, it began less with a plot than what he calls “opportunities for advancement.” “I don’t sit around and say ‘Fuck plot,’ but I don’t really know what people are talking about when they talk about plot. It all seems so kind of beside the point.” He prefers to think of what he’s doing as “shooting around and making connections.”

Back at Rite-Aid, he spies a half-hidden shelf: cards for veterans returning from war. He pulls out one that’s blank inside. On its cover is the iconic silhouette of soldiers planting the flag at Iwo Jima, with no accompanying text. “Was that ’45?” Lipsyte asks, noting that it matches his wife’s age. “It’s a metaphor. After arduous struggle and great sacrifice …” Then, as Billy Joel belts out “Say Good-bye to Hollywood” across the overlit aisle, he pivots. “Let’s check out the chocolate situation.”

*This article originally appeared in the March 11, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.