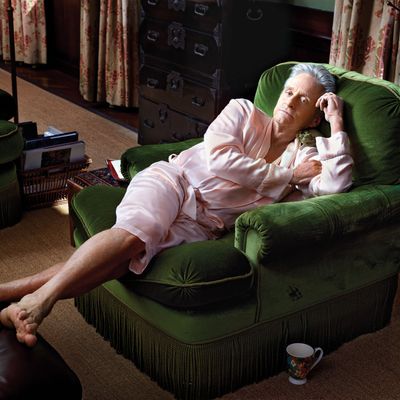

The only thing that worried Michael Douglas about playing Liberace, the flamboyant Las Vegas superstar, was the fourteen-inch penis. “It may not have been fourteen inches,” Douglas explained to me on a cold spring afternoon, “but it was huge.” He was sitting in a plush, forest-green velvet club chair in the study of his Manhattan apartment overlooking Central Park West. Douglas’s gray hair was combed straight back from his face in a kind of lion’s mane, and he was dressed in head-to-toe black.

The brightness of the day was streaming in from the windows, which had the effect of backlighting: Between the silver hair, the dark clothes, and the naturally cinematic setting, Douglas looked like someone accustomed to the spotlight. “Liberace loved sex,” Douglas continued, “and I didn’t have a problem with that. But, at one point, Steven Soderbergh [the director of Behind the Candelabra, which airs on HBO on May 26] wanted to show Lee [as Liberace was known] watching a gay porno. I said, ‘Steven—you can’t do this!’ He said, ‘It’s HBO—it’s all right!’ I said, ‘It’s not that: I’d like my kids to see this R-rated movie, but I don’t want to show them a fourteen-inch dick!’ It was the only thing I objected to, so we cut to different parts of the apartment during the porno.” Douglas paused. “You know, Lee also loved to decorate. He had his passions: his career, his homes, which were over the top, and his private life as a gay man.”

Although it was only a few decades ago, Behind the Candelabra takes place in another world, a place where being openly gay and famous was viewed as an impossibility. For Liberace, who sued a London newspaper and won when it insinuated about his sexuality, revealing his lust for men would have been, in his mind, career suicide. The movie, which isn’t really a biography, is the story of Liberace’s life with Scott Thorson, a naïve 18-year-old (perfectly played by Matt Damon with wide-eyed innocence mixed with the entitlement of youth) who was Liberace’s live-in boyfriend for five years. Their relationship—Liberace was 57 when they met backstage at one of Lee’s sold-out Vegas extravaganzas—was intense, bizarre, and, despite the glitz and glamour, remarkably like that of any married couple. “I wanted to make something really intimate,” Soderbergh said. “I liked the Sunset Boulevard aspect of Lee and Scott—older, younger; powerful, not powerful. With some show business thrown into it. During his career, Liberace was the most successful act to play Vegas—he made up to $400,000 a week during the seventies—but he was very private. The film is about a part of his life that he didn’t share with anyone; it is an act of imagination, but I wanted it to be sincere. I didn’t want it to be unkind, because everyone loved Liberace. He was the nicest man.”

For Douglas, the sexuality of Behind the Candelabra was the easiest part to get right. The movie is something of a career rebirth—in the past few years, Douglas was diagnosed with life-threatening cancer, and his oldest son was sent to prison. There is a boldness in his portrayal of Liberace—a combination of showbiz grit, longing for family, and intense vulnerability—that seems to mirror Douglas’s recent hardships. In his long, over 40-year career—playing everything from Gordon Gekko, a titan of Wall Street (for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor), to the philandering husband in Fatal Attraction to a compromised cop in Basic Instinct to a pot-smoking novelist in Wonder Boys—Douglas has always been a Zeitgeist-y embodiment of the modern man. Which means he has never worn prosthetics in a movie, let alone a rhinestone-encrusted floor-length fur cape decorated with sequins. “I was the girl on this movie! The hair and makeup for Liberace took two and a half hours,” Douglas said. “I’ve never done elaborate hair and makeup before. Up until now, my entire career has been contemporary.”

Part of Douglas’s movie persona has always been a willingness to be bold in sex scenes. In what he jokingly refers to as “the sex trilogy”—Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct, and Disclosure—he was often naked (from behind) and, especially in Basic Instinct, the sexual couplings were quite graphic. “I wanted to do a real fucking slam dance in Basic Instinct. And we did.” Behind the Candelabra is similarly explicit: The pre-Viagra Liberace had a silicone implant in his penis to ensure erection, and Douglas does not shy away from this information and all it implies. “Once you get that first kiss in, you are comfortable,” Douglas said. “Matt and I didn’t rehearse the love scenes. We said, ‘Well—we’ve read the script, haven’t we?’ ” Douglas laughed. “The hardest thing about sex scenes is that everybody is a judge. I don’t know the last time you murdered somebody or blew anyone’s brains out, but everyone has had sex and probably this morning, which means everyone has an opinion on how it should be done.”

The sexual content—the gayness of Behind the Candelabra—made it a tough sell to the studios. It was originally conceived as a feature film rather than an HBO movie, but none of the major movie companies wanted to finance the film, which cost only $23 million and featured two major stars. “Everybody loved the script [by Richard LaGravenese, based on Scott Thorson’s memoir of his life with Liberace],” said Jerry Weintraub, the veteran producer who worked with Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra and knew Liberace. “The party line was that Behind the Candelabra would not appeal to anyone who is not gay. Interestingly, they forgot that Liberace’s own audience in the fifties and sixties was not gay. It was purple-haired ladies who loved his act—he knew how to take the audience upside down, sideways, and backward. He was an artist, and yet, when I saw him at his house, he was free and open with his sexuality. There were men in every room! I didn’t care—it just meant there were more women for me!”

Weintraub, who produced the movie, had been down this road before: In the seventies, he produced Cruising, which starred Al Pacino as a cop hunting down a serial killer in the homosexual leather scene. The movie was going to receive an X for “a penis inserted into a guy’s behind,” said Weintraub. “The studio was afraid to put it out, but it made them a fantastic amount of money.” Neither Weintraub nor Soderbergh gave up: For reasons that he can’t explain, Soderbergh had been interested in Liberace as a topic for years, and while they were on the set of Traffic in 2000, he had asked Michael Douglas about playing him. “I was cast in Traffic as a government drug-enforcement czar in a gray suit and tie,” Douglas recalled. “And Steven came up to me and wanted to know if I ever thought about playing Liberace.” Douglas laughed. “I thought he was playing a game with me—like it was some mind-fuck trick to get me into the character. But I played along—I imitated Lee’s voice briefly for him, and we went on with making Traffic.”

Although he wasn’t sure if Soderbergh was serious, Douglas, too, had an immediate attraction to the bravado and complexity of playing Liberace. In many of his films (with the huge exception of Wall Street), he is usually the nice guy who is surrounded by extreme characters, mostly women—whether they be psychotic killers or wronged lovers or some combination of both. While he is not a particularly self-reflective person, Douglas is aware that his considerable charm, both on-camera and off, can be a protective device, an area in which to operate safely. “I do feel I get dismissed sometimes,” he said. “It may be a second-generation-Hollywood thing—my father [Kirk Douglas] was known for tough-guy parts, and I probably gravitated toward the cerebral rather than the physical to be different from him.” Having worked as a producer—at 31, he won the Academy Award for Best Picture for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest—Douglas was also more interested in the film as an entity, rather than the stellar nature of his individual part. “I always wanted the movie to be good, rather than just my part or my performance,” Douglas continued. “If a movie is good, it works out for everyone. And that was, selfishly, always my goal.”

With Liberace, Douglas saw the possibility of both an exceptional part and a compelling movie. “I also had a strong memory of Liberace,” Douglas said. “I met him once with my father in Palm Springs, where they both had homes, but what I mostly remember is Lee’s TV show. Liberace talked directly to the camera—he was the first person to do that. He was having such a good time that he was contagious. For me, Lee’s gayness didn’t even enter the picture—you just wanted to share the good time with him. And he was nice. I was attracted to his sheer likability.”

By 2010, Soderbergh had offered the part to Damon, who signed on instantly. Douglas received the finished script, and HBO had agreed to finance the film, which will be broadcast on TV in America and released in theaters outside of the USA. “When Soderbergh said that Matt wanted to play Scott, I was impressed,” Douglas recalled. “In the prime of my career, I don’t think I’d be choosing to play Scott. I mean, he has to wear a white sequined thong! That takes real guts.” Douglas laughed. “We were ready to go,” Douglas said flatly. “And then I found out I had cancer. That put things off for a while.”

For around a year, starting in 2010, Douglas hadn’t been feeling well. “I knew something was wrong,” he said, speaking slowly. “My tooth was really sore, and I thought I had an infection. I had two rounds of appointments with ear-nose-and-throat doctors and periodontists. They each gave me antibiotics. And then more antibiotics, but I still had pain. I went to Spain with the family [Douglas has two young children, Carys, 10, and Dylan, 12, with his wife, the actress Catherine Zeta-Jones, and a son, Cameron, with his former wife, Diandra] for the summer, and when I got back, a friend suggested I go to his doctor in Montreal. That doctor told me to open my mouth, took a tongue depressor, and then he looked at me. I will always remember the look on his face. He said, ‘We need a biopsy.’ There was a walnut-size tumor at the base of my tongue that no other doctor had seen. Two days later, after the biopsy, the doctor called and said I had to come in. He told it me it was stage-four cancer. I said, ‘Stage four. Jesus.’ And that was that.”

Perhaps because he’s better now, or perhaps because it is part of his nature to remain charming rather than melodramatic or self-pitying, Douglas talks about his cancer in an almost distant way, as if telling a story about someone else. After the diagnosis, Douglas began an intensive eight-week program of chemotherapy and radiation. The radiation burned the inside of his mouth, and eating became nearly impossible. “If you get a feeding tube, you quickly lose the ability to swallow,” Douglas explained. “They recommended that I try to eat and I never got the feeding tube. Matzo-ball soup was great, but I still lost 45 pounds.” Douglas paused. “That’s life,” he said finally. “Things had been going good for me for a long time. I was ready for some karmic retribution.”

Ironically, before becoming ill, Douglas had completed work on both Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, the sequel to Wall Street, and Solitary Man, an independent movie about an aging, self-destructive Lothario with a severe heart condition that he ignores. Douglas is extraordinary in Solitary Man—dark, haunted, and intensely lonely. Even though he was ill, Douglas decided to promote both movies, and after the first week of radiation and chemo, he went on The Late Show With David Letterman. He discussed his medical condition in a surprisingly candid manner: Letterman seemed stunned. At one point in their conversation, after Letterman commented on how great he looked, Douglas replied, “[It’s] because I’m onstage. Kirk would say, ‘Son, you’ve got to look good, you never know when you might have cancer.’ ”

It was (sort of) a joke, but grace under pressure mixed with tenacity is one of the keys to Douglas’s personality and his longevity as a performer. He is old school in the sense that you tough out the bad times and, you hope, don’t reveal more than you want seen. “When I was ill, I mostly lay on that couch,” he said, pointing to the forest-green sofa. “I watched a lot of sports, anything where I didn’t know the ending.” I asked him if he missed working. “I did, but I was too weak to miss much of anything. I was stage four, and there is no stage five. After complaining for nine months and them not finding anything, and then they told me I was stage four?! That was a big day.”

In 2011, after his treatment finished, Douglas flew to L.A. to present an award at the Golden Globes, where he was also nominated. As he walked onstage, he received a standing ovation. He looked scary-thin, but his famous hair was swept back, and the elegance of his tuxedo helped compensate for his weight loss. After the applause died down, Douglas said to the audience, “There’s got to be an easier way to get a standing ovation.” There was nervous, concerned laughter, but it is a sad fact of Hollywood that beating death is a good thing for a career: His cancer made the movie business appreciate Douglas again.

“Cancer does give you a new rejuvenation,” he admitted. “I know what it’s like to be down. I lost a couple of good friends—Larry Hagman and Nick Ashford—who had the same type of cancer that I did, and that makes you think. In the past, on purpose, I’ve never known what movie I’m going to do next. I never knew how I would feel when I finished a picture. Now it feels great to be back at work. Maybe that’s the benefit of taking a break with cancer: Then, people say, ‘What happened to him? Please come back.’ ”

Two weeks later, on another chilly spring day, I returned to Michael Douglas’s apartment. He was late for our meeting—he and his family live primarily in Westchester now, where his kids attend school, and he was stuck in traffic. During his illness, Douglas would walk his daughter Carys to her school in Manhattan and the paparazzi would hound them. That was when he decided to leave the city. Douglas, who lived in Los Angeles for less than two years in the eighties (and sold his house, unknowingly, to the notorious madam Heidi Fleiss), has always considered New York his home. He is close to an impressive array of the power elite—at his private screening of Behind the Candelabra, luminaries like Michael Bloomberg, Barbara Walters, and Maureen Dowd were in attendance. Douglas missed most of the evening—his watch stopped—and arrived as his guests were leaving. “Bloomberg called me later to say he loved the movie,” Douglas told me, “but he had to run off to a dinner for Kissinger.”

Douglas lived in this apartment with Diandra and Cameron for a decade and then, after the divorce, shared it with Zeta-Jones and their children. He first saw Diandra across a crowded party at the Kennedy Center the night before Jimmy Carter’s inauguration in 1977. They married two months later, and decorated the apartment with some rather theatrical antiques—a dark Russian bureau, some neoclassical busts that remain—but the plump sofas, once covered in delicate Fortuny fabrics with silk tassels that took two years to create, are now upholstered in sturdy chenille. The large apartment is anchored by a huge room that has been divided into three sections: the living area (in gold) and the study (in green) are separated by a full-size pool table. To the left of the gold couch and chairs is a formal dining room, with a grand table that could easily seat twenty. The dominant decorative details in the main room are photographs: dozens of photos of family, of famous faces in politics and show business, of Douglas through the years, encased in separate sterling-silver frames and placed on a central table.

As I was studying a photo of him with a bevy of First Ladies, Douglas came into the room. He was wearing light khaki pants and a matching cashmere sweater. He looked like he had just walked in from a golf course, which may have been possible—he is passionate about golf. “Let’s sit in the middle this time,” he said, settling himself into the gold version of the green chair. He took out his iPhone. “Look at this,” he said. It was an ecstatic e-mail about another one of Douglas’s upcoming films, Last Vegas, in which he plays an about-to-be-married bachelor out for a final hurrah with his buddies (played by, among others, Robert De Niro and Kevin Kline) in Las Vegas. The film had tested through the roof. Douglas looked a little stunned. “I had a great time making it, and that always worries me. It usually means the movie will bomb.” He looked back at his phone. “It’s hard to get excited, but I’ve been down so long, things are starting to look up.”

Douglas had been hoping for other good news. Cameron, who is 34, is in jail for drug possession and dealing. His case was up for appeal, and Douglas was waiting to hear the verdict, which was expected any day. Cameron was in prison when Douglas was diagnosed with cancer, and Douglas believes that the stress from Cameron’s horrible situation may have exacerbated his illness.

“Since he was 13, Cameron has been a chronic substance abuser,” Douglas began, speaking in a resigned, almost forlorn voice. “He was kicked out of school for dealing pot when he was 13, and that’s when I became aware of his problems. He’s a wonderful, talented kid who I love to death, but when heroin became his drug of choice in the last eight years, the situation became difficult. He was shooting up seven times a day. I knew that was going on. Cameron had a minor allowance which provided for his living expenses, but it didn’t pay for shooting up heroin seven times a day, which is $700 or $800 a day—times seven, which is around $5,000 a week. So he became a crystal-meth dealer, which is probably the most disgusting drug there is, to support his habit. At the time, he was living in California and was under investigation by the DEA. He got caught in a DEA drug sting, and he was offered either a ten-year sentence or the chance to cooperate with their investigation. His first call was to me, and I said, ‘You should cooperate.’ Naming names when it comes to drugs has a bad connotation, but the reality is, everyone talks. And it’s better than being in jail.”

From that point on, Cameron’s story gets messy and depressing: He was put under house arrest and had his girlfriend bring him heroin, which was confiscated. Before his trial, one of his lawyers smuggled in some Xanax, which he used to self-medicate. Both those transgressions cast a dim light on his case, and he was sentenced to five years in a federal prison in Pennsylvania. On the verge of beginning a nine-month drug-rehab program, he had a “drug slip.” His urine tested positive for opiates, and he was caught with one-eighth of a pill of a drug called Suboxone. Owing to these setbacks, the judge added a devastating four and a half years to Cameron’s sentence. Viewed as a risk, he was also sent to solitary confinement for eleven months, and family visits were denied for two years.

“I have gone from being a very disappointed but loving father who felt his son got what was due him to realizing that Lady Justice’s blindfold is really slipping,” Douglas said. “I’m not defending Cameron as a drug dealer or drug addict, but I believe, because of his last name, he’s been made an example.” Douglas paused. “I could have strangled him,” he said finally. “When he had the ‘slip,’ I said, ‘You were two weeks away from starting your rehab program!’ But years of shooting up heroin screws up your system.”

Douglas believes that a propensity for addiction is part of the genetic makeup of his family: His half-brother Eric died of an accidental drug overdose; his brother Joel is a recovering alcoholic; and Douglas himself went to rehab in 1992 for what the press said was sex addiction but which he insists was for exhaustion and alcohol abuse. “I went right after Basic Instinct,” Douglas said. “People said it was for sex addiction because Basic Instinct was in the air. But it was really because I was depressed after I lost my stepfather, whom I was very close to. I went through a rough time.” Catherine Zeta-Jones recently went to a health-care facility for a second time to treat her “bipolarity.”

Douglas shrugs off nearly all talk about the perils of fame. “And I also don’t think about being strong. It’s not how my mind works.” I reminded him that he once told me his greatest motivation was revenge, that when he was struggling to get Cuckoo’s Nest produced, he dreamed of the day he could see one of the naysayers at lunch and say, “Hello, I’m celebrating my hit picture. Nice to see you again.” Douglas laughed. “A lot has happened between then and now,” he said. “But I still know how to fight.”

Until he went to college at University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1963, Douglas had no plans to become an actor. “I was conscious of my father’s fame from the time I was 6,” Douglas told me. “We flew to France, where he was making a movie called Act of Love, and photographers met our plane. That was the beginning.” Douglas’s parents divorced when he was 7, and he grew up in Westport, Connecticut, with his mother and stepfather. He would visit his dad during the summers, often on set. “From fifth to seventh grade, I went to Los Angeles for high school,” he recalled. “I was 11, and I had my first kiss. She was, of course, 13 and five-foot-nine, and she had her mouth wide open and her tongue down my throat. No one ever told me about French kissing! I freaked out: What is this snake?!”

At UCSB, Douglas became, in his words, a hippie. Eventually he was asked to declare a major, and he thought theater would be easy. “God bless Dad, he came to every one of my shows. I was bad, and I had horrible stage fright. My dad was so relieved—he’d say, ‘You were terrible, this kid is not going to be an actor.’ Finally, I did a play and he said, ‘Son—you were really good.’ ”

Douglas was cast in The Streets of San Francisco in 1972 as the rookie partnered with Karl Malden’s veteran cop. “That was the first time I was famous on my own,” Douglas said. “Being second generation in Hollywood is complicated: Success is expected, and yet the track record of the second generation is not great. Only a small group of us, like Jane Fonda, have succeeded. The good and the bad of being second generation is there are no illusions: I always knew that this was a business. It can be wonderful, but it is a business.”

For many years, Kirk Douglas had owned the movie rights to Ken Kesey’s novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. He had starred in the theatrical version on Broadway, which was not a hit, and was attempting to develop a film version. Frustrated, Kirk was about to sell the rights to Cuckoo’s Nest when Douglas asked him if he could try to set up the movie. “I worked on it for over five years,” he recalled. “And when we finally got it going, my father’s career had changed. He’d become a little older, and our director, Milos Forman, did not think he was right for the lead role. That was probably the most difficult moment in the history of my life with my father. I kind of said, ‘The good news is we’re getting the movie made. And the bad news is, the part is going to Jack Nicholson.’ Now I understand. When you see a great part, you want to grab it.”

Luckily, Cuckoo’s Nest was a massive hit on every level—it made over $100 million, and it won the Academy Award for Best Picture, Director, Writer, Actor, and Actress—and Michael Douglas was suddenly heralded as a great producer. “I remember we were all sitting around after the Academy Awards, and I said, ‘It’s all downhill from here,’ ” Douglas said. “Whether it was true or not, I wanted to set that attitude so life would not be a disappointment.”

Douglas spent many months flying all over the world with the film (“Everyone is really happy to see you when you’re 31 and you’ve just won the Academy Award. We were on tour right behind the Eagles—literally and figuratively”), and when he returned to California, no one wanted him to act. “My agent, Ron Meyer, used to joke that he’d be in meetings and he’d raise his hand and say, ‘Does anyone have a bone here for Michael Douglas? He wants to act.’ ” Around this time, it became clear that studios underestimated Douglas as an actor, so he began producing movies that had a good part for him. In The China Syndrome, an anti-nuclear thriller, he played a sexy TV cameraman; in Romancing the Stone, he played a sexy adventurer. “When I produced Starman in 1984, I had to put Jeff Bridges in the starring role because the studio would not approve me.” Instead, they offered Douglas two studios to run—Warner Bros. and Disney—but he said no. “I wanted to act,” Douglas maintained. “I always wanted to act.”

Everything changed in 1987: Within four months of each other, Fatal Attraction and Wall Street came out. In both, he was cast as a dark character. Douglas’s father had always told him to play a villain: “You’re gonna do a great killer,” Kirk said. “You’re such a charming guy, but they’re gonna find out the prick you really are.” In a peculiar way, Kirk was wrong: Even when Douglas played the bad guy, his charm held. Although Gordon Gekko was conceived as a villain, Douglas’s personal charisma made him, instead, a role model. “Every time I’m out, a drunken Wall Street guy comes up to me to say, ‘You’re the man,’ ” Douglas said, shaking his head. “It’s depressing. Gordon Gekko was not a hero.”

In Fatal Attraction, Douglas knew the exact moment he seduced the audience. “At our first screening,” he recalled, “there was laughter when I came back to the family apartment after the first night of the affair and mussed the bed to look like I’d slept there. The producer, Sherry Lansing, turned to me and said, ‘I can’t believe it: They’ve forgiven you already. You are blessed with the gift of charm.’ ” He smiled. “It made me wonder: What can I get away with? How far can I go?”

The same week that Cameron Douglas lost his appeal for a lighter sentence, the chosen entries in the Cannes Film Festival were revealed. In an unusual and highly complimentary move, the festival put Behind the Candelabra in competition. Thierry Frémaux, the head of the festival, had been so impressed by the movie that he begged Soderbergh, who has said that the Liberace film would be the final movie he directs, to allow the film to have a prominent place in Cannes.

As always, Douglas was calm about both the good and the bad news. He was unhappy but not surprised about Cameron’s jail term and proud but not surprised about Candelabra. He was quietly confident about his work. During the wait between the end of his cancer treatments and the start of production on the Liberace film, Douglas had immersed himself in the character. He read books on Lee, watched his Tonight Show appearances, talked to Kirk and anyone else who knew him. “I never heard a bad word about Lee,” Douglas told me. “From the stagehands to Debbie Reynolds, who plays Lee’s mother and told me some great stories about Lee’s sex life. People went on and on: They all loved him.”

The Liberace story could easily have been turned into a campfest, full of superficiality and razzle-dazzle. Instead, both Soderbergh and Douglas were interested in something they both value greatly: a kind of professionalism and sense of commitment that represents the best of Hollywood. “Liberace worked hard,” Douglas said, echoing Soderbergh’s earlier statements. “When Scott Thorson became a drug addict and Liberace’s work was imperiled, their relationship cratered. When I watch the movie, I forget it’s Matt and me pretty quickly. And soon after that, I forget it’s two guys. The fights, the love—it’s a couple. There’s always that moment in a relationship where somebody has gone too far or they’ve done something that can’t be forgotten, and, suddenly, a little tendon is popped, and it never comes back. The only people you can forgive after something like that is your family. Lee tried, but he couldn’t forgive Scott until he was about to die.”

It was impossible to tell if this reminded him of Cameron, or his own illness, or if he was simply interpreting the movie. “My father had a tough time watching my death scene in Liberace,” Douglas said. “He was here when I was sick, and it was very hard for him. When he watched me die in the film, he did not say a lot.” Douglas paused. “My father is 96, and he’s still a really competitive guy,” he said. “I tease him and say, ‘Let the legacy go on!’ Fathers and sons: They may want to beat you, but they still love you. Who else can you say that about?”

*This article originally appeared in the May 20, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.