How many New Yorkers have a recurring dream of discovering an extra room in their apartments? The Met has dreamed that dream and made it come true. In effect, it has discovered 45 new rooms in its already magnificent house. The museum has rethought and reordered its premier collection of premodern European paintings, added or moved over 700 artworks (up from the roughly 450 that were on view a few months ago), and carved out new galleries from spaces formerly devoted to rotating exhibitions. The results are profound. The new installation, with its better lighting, spacing, labeling, and wall colors, presents us with a much more coherent, legible vision of one of the great achievements of world civilization—Western painting—and one of the great collections of it, making the greatest encyclopedic museum of art in the world greater by leaps and bounds. Greater in ways that might alter art and change minds—especially those of young artists and historians who seem blasé about art made before 1900.

I especially appreciate that the Met did this not by spending hundreds of millions of dollars on some newfangled, architecturally driven, funny-shaped ark of a building with traffic patterns that force you to smell food while looking at art. The Met did what living organisms do—it found the stuff to evolve and build anew within its own tissue. The change is so sweeping that every Met aficionado I know—including people who visit the museum 20 to 30 times a year—is confessing something no one ever wanted to admit. Before this recalibration, all of us occasionally had no idea where we were in these galleries.

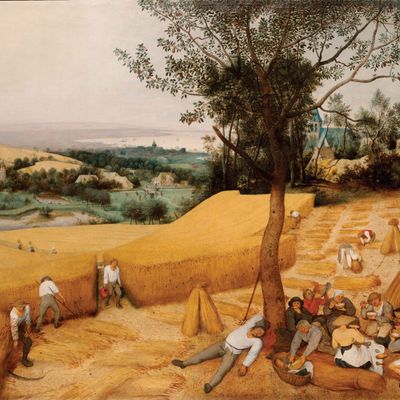

I regularly got lost looking for Rubens, forgot where Bronzino, the Mannerists, and Caravaggio were. Even Bruegel’s tremendous masterpiece The Harvesters, with its real people in a real world doing real things and maybe the most yellow painting ever made, could pop up where I thought Dürer and Cranach were. I couldn’t even quite place the $50 million Duccio and kept flipping it in my mind with Memling and Patinir. Not only was this bewildering; it was misleading. Formerly, if you turned right from the first grand gallery of gigantic Tiepolo paintings of mythic beings in centerless swirling space, proceeded through a second gallery of his paintings (that has thankfully been left the same), you’d find yourself not seeing how these painting-machines and polycentric spaces came into existence but—out of nowhere—in the middle of a handful of paintings by Goya. You’d have no idea of how this happened, or about the political, pictorial, and psychological ruptures Goya signifies—he just looked fanciful and Spanish. Next, you were led to the super-Proust of painting, Boucher; then to painting’s Shakespeare, Velázquez. In the space of three galleries, you went from the Italian Baroque to the visionary Spaniard to a luscious Frenchman to one of the highest peaks in all art. (Gainsborough was sandwiched in there, too, and for decades came off as painterly roadkill.) This being the Met, and the art being so extraordinary, we didn’t grouse about it much.

The new installation reveals itself in complex, unforced ways like a cosmos of multitudes blossoming before our astonished, grateful eyes. I saw indefinable essences I’d never seen before on each trip. But I wanted to put the installation to the test. Rather than taking the new paths that will be most traveled—the glorious trails that take us through the flowerings of Florentine or Sienese Renaissances; or the ones that lead us through Netherlandish and Northern painting to the Dutch—including the endorphin-releasing gallery containing five of Vermeer’s 36 known paintings, works that alight on your body like tender healing mercies—I took the Goya-to-Gainsborough route that used to perplex me.

Now, after Tiepolo’s convoluting space, you can go straight to sixteenth-century Rome. A wall of four large works by lesser-known Panini has views of Rome: shrewdly conceived spatial arrangements that give us Roman collectors and dealers packaging their ancient and contemporary wares and ruins for the moneyed English tourists then making their way to Italy. This gallery has two more entry points. Take one and you see artists doing a similar thing to Venice. Canaletto’s vertiginous organized space hypnotizes; Guardi’s traffic jams on the Grand Canal are muddy and mouthwatering. Look at these paintings; recall the hotel you stayed in; point it out to whoever’s beside you; you will both feel like citizens of the world.

Take the other entrance and behold yet another high point: a gallery with four Caravaggios. Here is the captivating evolution of the naturalistic via dramatic lighting and the birth of the cinematic in painting. And steamy sexiness! See if you can look at the androgynous lute player and not remember that singer you once fell in love with. Swoon at the boy band of madly sexual musicians, each with dreamy come-to-my-hotel-room eyes. This is visual Viagra, painterly genius, and among the most influential artistic DNA ever generated.

Then come galleries of paintings of Rome again—this time, however, by the Frenchmen Claude and Poussin, who combine classicism and romanticism to create sophisticated compositions that almost step outside of time. We witness human figures turning into geometry. Then comes another turning of the evolutionary screw: See the human species evolving before your eyes in the joie de vivre and longing, the modernity and disruptive internal insights, of Boucher, Fragonard, and the incomparable Watteau. This is the moment before the French Revolution. You know it; so do the people in these paintings. Even the foliage seems to creep up on these beings. Fragonard’s tiny scene of an overgrown wooded path is now my favorite small, foreboding painting in the Met.

Heart pounding, exhausted, I finished one of my visits by looking a few rooms ahead, to the point farthest from the entry gallery on this route. There, finally, is the perfect painter placed at the end of this line of European painting: Goya. He correctly stands alone, as the hinge between the past and the present, the premodern and the modern, the alchemist who combines vision and observation with profundity. The Met and its lead curator on this project, Keith Christiansen, are owed a debt of gratitude for this splendid resetting of the compass.

New European Paintings Galleries, 1250–1800. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

*This article originally appeared in the June 17, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.