Pop music is an exceptionally open art form, accommodating of all kinds of ideas, including those that, in different contexts — without a tune or a backbeat — might be laughed off as embarrassing or scorned as tasteless. There’s nothing necessarily ridiculous, therefore, about a plaintive country-rap power ballad in which a black Starbucks barista and a white guy in Confederate flag t-shirt work out their racial animosities, and puzzle through the legacy of slavery, presumably while knocking back iced grande Lattes.

In practice, though, the Brad Paisley–LL Cool J duet “Accidental Racist” landed on the Internet this past spring with a thud. The song was cringe-theater: a mix of earnest and tone-deaf, with a Cool J rap whose weirdly conciliatory stance — “If you don’t judge my gold chains/I’ll forget the iron chains” — that neither the song’s obvious good intentions nor Paisley’s guitar-picking could redeem. The howl of condemnation that greeted “Accidental Racist” was understandable, given the touchy subject matter. It was also unfortunate: “Accidental Racist” is as audacious as it is awkward, a fact that was lost on those unfamiliar with country music, and with Paisley’s own genially tricksterish approach to the genre’s cultural politics.

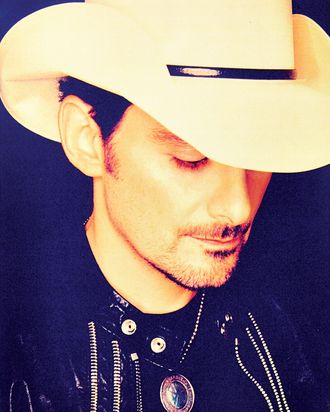

For more than a decade, Paisley has been a superstar: country’s sharpest songwriter, most fearsome guitar player, and biggest cut-up. He’s also a progressive figure, who has slyly challenged the most conservative constituency in popular music. Four years before “Accidental Racist,” Paisley released American Saturday Night, an album that celebrated New York City’s multiculturalism and, in the anthemic “Welcome to the Future,” hailed the election of Barack Obama. In the 2011 single “Camouflage,” Paisley cheekily advocated replacing the Confederate stars-and-bars with a redneck symbol that causes no offense: a camouflage flag. It was a very Paisley move: politics that defied the country music party-line, smuggled onto the charts under the cover of a joke, a catchy tune, and a wicked guitar solo.

Paisley’s ninth studio album Wheelhouse, released in April, is the most flamboyant example yet of his iconoclasm. It’s one of the year’s most fascinating records — a grab bag that takes in unlikely genre mash-ups, dabbles in hip hop–style production, and features a wacky roll call of guest stars. (Monty Python’s Eric Idle appears in one song.) The album’s provocations include not just “Accidental Racist,” but “Those Crazy Christians,” a gospel testimonial that makes room for atheists and admits that there’s something a bit nutty about devout belief. Then there’s the album’s woolly, ambitious centerpiece, “Southern Comfort Zone,” in which Paisley turns the tradition of the Dixie home song on its head — endorsing globe-trotting cosmopolitanism and topping off a riot of signifiers by interpolating the old minstrel stage staple “Dixie,” with a reworked melody scored for full gospel choir. It’s a manifesto for an album in which Paisley determinedly strays from commercial country’s comfort zone, with results both spectacular and spectacularly messy.

Last month, I spoke to Paisley for several hours, sitting in his tour bus following a concert in Greenwood Village, Colorado, near Denver. We chatted for a bit about the show. I then told Paisley I had a bunch of questions I wanted to ask about “Accidental Racist.” “I know,” he said. “I want to talk about it.”

Let’s talk about the response to “Accidental Racist.” Did it take you by surprise? Did you expect that the song would generate the kind of controversy that it did?

The whole thing took me by surprise in this sense: This was a deep album cut on a country record. I didn’t know it was possible for an album cut to make the news, let alone to be headline news. It’s ironic because my publicist had reached out to NPR and said, “Brad has cut an album that takes a lot of risks and asks some really tough questions. Would you like an interview?” And they didn’t want one. Then, all of a sudden, I’m driving to go play Leno, listening to NPR. And they’re devoting Talk of the Nation to this subject, on the album release day.

The truth is, I mostly thought about “Accidental Racist” in terms of my fans. This song was meant to generate discussion among the people who listen to my albums. What I was most worried about is that my fan base would think that I was preaching to them. The last thing I ever want to do is be preachy. But I thought that my fans would get something out of hearing a point of view that they don’t hear very often — a perspective you really don’t hear in country music. Some Southerners got very mad it me: “I’m done with you. How dare you apologize for the Confederate flag.” But the majority of my fans said, “We know you, we love you — and we don’t understand the controversy, we don’t get why everyone is so mad.” Which tells you all you need to know, right there. There is a gulf of understanding that I was trying to address.

The most surprising and upsetting thing was being thought of by some as a racist. I have no interest in offending anyone — especially anyone in the African-American community. That song was absolutely, earnestly supposed to be a healing song. One hundred percent.

Did you read any of the criticism of the song?

I did. I read the serious criticism — the stuff that was legit. Some of it I understood; some it I didn’t. I’m eager to read more. This is a learning experience for me.

Many critics objected to what they viewed as the song’s simplistic treatment of a complex subject. Some people felt that “Accidental Racist” aimed to “put to bed” the problem of racial animosity and the legacy of slavery — to reduce all that history to a misunderstanding that could be resolved by two guys talking at Starbucks. The song’s lyrics seemed to draw a comparison between the Confederate flag — viewed by many as a symbol of white supremacy, of an unspeakable historical crime — and the fashion choices of a black man: his sagging pants and gold chains.

If there’s a key line in the song — and this was really criticized, really taken out of context, in my view — it’s the line “It ain’t like I can walk a mile in someone else’s skin.” That’s a line about the character’s limitations, as a white man, his inability to truly understand the experience of an African-American. The point isn’t that I have the answers or that I’m offering easy solutions. It’s the opposite. It’s that this is a difficult problem — and that I want to have a conversation about it.

Yes, I wanted the song to be about the Civil War and slavery. This song is about reconstruction, which is still going on. It’s a song about a great sin that we’re still dealing with. And it’s a song, in a way, about profiling — about the assumptions we make about people who we don’t really know. It was meant to be a story of two individuals — LL and I, or the two characters we “play” in the song — having a very civil conversation about these difficult issues.

Here’s what I know now, though, that I didn’t know on April 8th. You can sing to a woman and say, you know, “If you cheat on me, I’ll forgive you” — and the entire male population won’t turn on you and say, “How dare you say that on our behalf.” But when LL says to me in the song, you know, “If you don’t judge me for this, I won’t judge you for that,” people will say: “How dare you say this on our behalf.” I realize now that you can’t personalize the conversation about this subject in the way I tried to in the song. I was naïve about that.

No one cared more about getting this right than LL and I. We had no interest in being flippant about this. We both worked very hard on what we wanted to say. And that’s the thing that allows us to sleep.

Why did you pick LL as your duet partner? He’s not known for his politics. Some critics have suggested that if you wanted to have a challenging conversation about race, you would have chosen a more politically astute rapper, a rapper known for dealing with racial politics.

I wanted to this with LL because I love his music, and because he’s a legend in his format. And I didn’t want to do this with someone controversial. You have to remember my thought process: I was thinking about the reception from my audience. My fear was, I didn’t want my fans to just write it off. I didn’t want them to dismiss the song and its message. I thought about approaching Kanye. Mike Dean, who works with Kanye, produced “Outstanding in Our Field” [on Wheelhouse]. But it would have instantly been polarizing if I’d gotten Kanye. Half of my fans are still mad at him for taking Taylor Swift’s mic!

Look, no one dislikes LL Cool J. If you meet LL Cool J, you fall in love with LL Cool J. LL and I had mutual friends, and he and I had always talked about doing something. My fans know LL’s music. And I love him — we’re blood brothers at this point. We’ve been through the fire together. I know no finer person.

Tell me about the recording of “Accidental Racist.” How did it come together?

LL came down to Nashville. I’d worked all night on a demo. I recorded the vocal at four in the morning. The next day, LL and I went to the Ryman Auditorium. Now, the Ryman didn’t have a balcony until the Civil War. They were bringing the soldiers home and they needed more seating. So they built the balcony and they named it the Confederate Gallery. It’s there in big gold letters. And so LL and I were getting the tour, and they explained to him they’d built the balcony for a reunion of Confederate veterans. And LL looks at me and he said, “What a country we live in, that you and I can stand here together after all that.” He had no idea what kind of song I’d written. So I said, “Come out to the car, I want to play this for you.” And he heard it and went, “This is important, I’m in.” He wrote his verse in the studio.

Have you ever worn a Confederate flag shirt, like the character in the song?

Yes, that’s part of what went into the writing of the song. I wore an Alabama t-shirt on a couple of TV shows. It was a vintage t-shirt, and my stylist sequined it out, put sequins on the letters of the Alabama logo. It was all blingy. And there was a flag on the shirt, too, about the size of a belt buckle. It was half-covered by my guitar. And then I read some stuff on the Internet reacting to it. Someone wrote: “Racist pig.”

I think the one thing that your readers might not understand is how prevalent that flag is in the South. You do see it everywhere. It flies on some courthouses, obviously. You see it all the time. I see it in the audience at my shows. Maybe you saw it out there tonight? It’s a complicated symbol. The truth is — again, your readers might not think this is possible — many, most of the people who fly that flag are not horrible people who want the South to return to the way it used to be.

Would you wear that Alabama shirt again now, after “Accidental Racist”?

That’s an interesting question. I haven’t since. If I put it on now — look, the last thing I want to be is racially insensitive. I don’t want to be hurtful to anyone. There’s lots of other stuff I can wear.

I think that’s the feeling that a lot of people have about the Confederate flag: why cling to a symbol that is so hurtful to so many people? Now, you’ve actually sung about the flag before, in “Camouflage” (2010). I’ve always thought of you as unique figure in country: a guy who — gently, often humorously — challenges your audience, tries to find ways to reconcile tradition and the modern world. In “Camouflage,” you embrace both racial sensitivity and regional pride: “Well the stars and bars offend some folks and I guess I see why/Nowadays there’s still a way to show your southern pride/The only thing as patriotic is the old red, white, and blue/Is green and gray and black and brown and tan all over too.”

Right, that was the joke — that was the point. Here’s a different thing that you can wear that says “southern redneck.”

The irony of the “Accidental Racist” controversy, for those of us who’ve followed your career, is that you’re known as a progressive figure in country, in particular on racial questions. You’re the country superstar that coastal liberals love to love. “Welcome to the Future” (2009) was a celebration of President Obama’s election.

When that album [American Saturday Night (2009)] came out, I was naively thinking that everybody felt the way that I did, which is proud that we’d come such a long way as a country. And then I realized that there are some people out there that don’t necessarily feel that way. I’ve had people say, “I’ll never sit through your concert again.” But most of my audience was incredibly embracing of “Welcome to the Future.”

Wheelhouse opens with “Southern Comfort Zone,” which was also the album’s lead single. It’s unusual song to find on a country album, to say the least: a song that says, “Be cosmopolitan. Get out and see the world.” And it’s fascinating, especially in light of “Accidental Racist,” the way you play with tradition in that song, the way you use “Dixie.”

“Southern Comfort Zone” is the album’s mission statement. You can write “Southern Comfort Zone” in ten minutes if you do it the obvious way. There’s somebody sitting in Nashville who’s mad at me saying, “I could have written the fire out of that and sold twice as many records with a song just about sittin’ on a tailgate.” When I thought about that title, I knew: That’s money in the bank. But the mode of this album isn’t money in the bank. We’re trying to do the thing you don’t expect out of country music. Which is to say, “Go see the world. It will make you love the South more. It will make you feel strongly about a lot of things.” This album was all about me getting out of my southern comfort zone. “Accidental Racist” is the prime example. It’s awkward and it’s messy. And it’s also exciting and fun. That’s the journey I’m on now.

One of the craziest collisions of worlds was doing that song on [Jimmy] Kimmel [Live]. When I got married I hired a great choir — the St. James Choir, an all-black gospel choir — to sing at my wedding. We were going to go do Kimmel, and I thought we might use them. My manager said, “But I wonder how they’d feel about doing ‘Dixie.’” And I said, “Ask them.” And they agreed to do it.

So we got up there [on Kimmel]. It was three months before the album was done. I’m singing “Southern Comfort Zone,” and the choir is taking the hair on the back of my neck — they’re standing it up and razoring it off. And I’m looking out on that parking lot full of people and there’s a couple of guys in the audience who have, like, a six-foot rebel flag. In Hollywood, mind you. Hollywood Boulevard. I’m looking at ‘em and I’m thinking, “Why are they doing that? Are they just proud Southerners that do not mean to offend?” I’m thinking, “Are you trying to make some statement here, because this is Hollywood? Is your point, ‘I love the South’? Or is it, ‘I wish that things were the way they used to be’?” As you can imagine, the whole last chorus of “Southern Comfort Zone” I was completely thinking about things to come. Like, what are they going to think when they hear “Accidental Racist”?

Let’s talk for a moment more about southern pride. In an article titled “Why ‘Accidental Racist’ Is Actually Just Racist,” the critic Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote, “Paisley wants to know how he can express his southern pride. Here are some ways. He could hold a huge party on Martin Luther King’s birthday, to celebrate a Southerner’s contribution to the world of democracy. He could rock a T-shirt emblazoned with Faulkner’s Light in August, and celebrate the South’s immense contribution to American literature. He could preach about the contributions of unknown Southern soldiers like Andrew Jackson Smith … ”

Sorry, I have to interrupt you. I like what [Coates] says, it’s smart. I’d love to talk to him someday. But I have to say this: Do you know what I did last year on Martin Luther King’s birthday? I played a show for the inauguration of our president. It was a really big party. I was a featured guest at a huge party on Dr. King’s birthday.

You didn’t just play the inaugural ball. You’ve performed at the White House twice, at President Obama’s invitation. The president has praised your music. I know that you’re friendly with the president, that you’ve met him on several occasions, and that you speak on the phone from time to time. Did you and the president ever have a conversation about “Accidental Racist”?

I’m sorry, I can’t comment on my conversations with President Obama. Those conversations are private.

Did you vote for President Obama?

I don’t talk about the people I vote for. You shouldn’t listen to my music for political messages. See, here’s the problem with talking about who I voted for. If I say I voted for Romney, then everybody’s like, “Of course.” If I say I voted for Obama, everybody’s like, “Of course.” And then I’m no longer the guy you can’t figure out.

Okay, but here’s what I could say to that: I could say that you’re just being a smart businessman. You’re playing it safe. You could alienate a significant portion of your fan base if, say, you copped to voting for President Obama.

Well, here’s what I’d say back to you: I think I’m being a sensitive artist and sensitive person. A person who respects other people’s opinions. There may be people in my audience who may not agree with me on some particular issue — you know, say, as a gun owner, they may not agree with me, or, you know, someone may not agree with me on a gay marriage topic. Any of those things. But those shouldn’t be the reasons you listen to my music.

I love being an enigma. Every time I’m tempted to respond to someone who tries to put me in a box, politically — you know, someone who gets on the Internet and says, you’re pro-gun, or you’re anti-gun — I stop and say to myself, “This is great, this is what I wanted. I wanted to be the guy you can’t figure out.” You don’t know if my next song is going to be about a pickup truck or if it’s going to be a weird gospel song called “Those Crazy Christians.”

“Accidental Racist” isn’t in your set-list on this tour. You’ve never played it live.

I might, though. You know, I could see us playing one time: LL and me, onstage at the Opry, with just an acoustic guitar, just having this musical conversation. I’ve toyed with that idea.

After all that’s happened, do you regret having released the song? Is this an idea that would have best been left on the cutting room floor?

Looking back at the whole thing — of course the song would still be on the record. Art should inspire discussion. Look, this started a journey for me.

You know, there came that point where I had to decide: Are you jumping off the cliff or not? And that’s what I did, just like the image on the [Wheelhouse] album cover. I knew that that song was a bit of the third rail for the record. You take that one off, and on the one hand I wouldn’t have gotten some really loud criticism from people I really respect and admire, like Questlove. On the other hand, you and I wouldn’t be talking right now, I don’t think. The thing is, this album isn’t about pleasing people, which is pretty unique for a country record. It’s about inspiring discussion.

I played [Late Night with Jimmy] Fallon the other night. I saw Questlove there, of course — I went up and introduced myself. But I never got to talk to him. Next time I’m in, I’d love to sit in with the Roots, who I adore. And I’d love to sit down and talk to Questlove, who criticized “Accidental Racist.” I’d love to hear more from him. The last thing I’m going to do with this song is write off the reaction of any African-American, especially a brilliant guy like Questlove. This is a learning process for me, you know.

I’ve always been able to laugh at myself. I consider myself a bit of a comedian. I write a lot of humorous songs. So now, I’m kind of the butt of the joke. I do standup once a year, when I host the CMAs. When all this happened, I said, “Well, I guess I gotta put myself in the monologue this year.”

In the middle of the whole thing in April, I was down in my kitchen and I got a call from my friend. He said, “You are not gonna believe what I’m looking at on my television.” I ran upstairs and I turned on SNL, and there’s Jason Sudeikis and Kenan Thompson, doing me and LL. I laughed as hard as anybody. I don’t care what you say about me that way.

I saw a funny tweet the other day: “Your song with LL Cool J gave me cancer.” I mean, you’ve gotta laugh at that.

*This article is an expanded version of one that appears in the September 30, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.