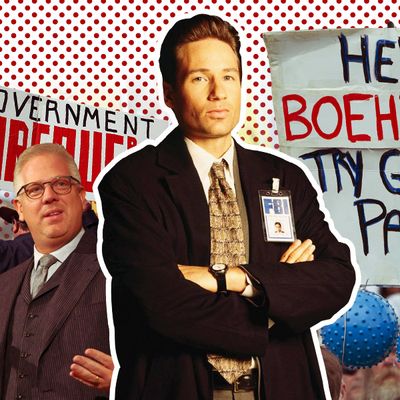

When the tea party first arrived on the political scene in January 2009, shortly after the inauguration of America’s first black president, I blamed Fox Mulder. With his quick quips, his nerd-jock appeal, and his quixotic, if monkish, hero’s quest, Mulder might as well have been their pop-culture avatar, the angry but noble muckracker that Patrick Henry wannabes saw themselves as, while waving misspelled posters as their versions of “the truth is out there” slogan — only in their case, the “truth” was President Obama’s Kenyan birth, his scheme to confiscate every gun in America, and his conspiracy to transform America into an atheistic socialist state and a radical Muslim theocracy.

My interest in The X-Files gradually dissipated after co-star David Duchovny’s departure as a series regular following the show’s seventh season. But my love for the groundbreaking program hardly dimmed, at least not at the time. Looking back, my hormonally charged obsession with The X-Files was probably the most formative relationship of my adolescence — yes, I’m aware of how pathetic that sounds — and not just because of the show itself, but how it coincided with and inspired a brave new world of fandom.

During those lonely high-school years, The X-Files was the gateway to a great many of my firsts, many not possible before the mid-nineties: reading TV criticism online, joining a listserv, losing many precious hours to fan fiction, discovering what exactly sex was from fan fiction, recapping episodes in private journals before recapping became a thing, learning about TV production schedules, coveting a Barbie. With its insistence on absolute truths and the hypocrisy of authority figures, The X-Files was a perfect accessory to innocent teen rebellion, like a Hot Topic T-shirt.

When Mulder insisted that a secret branch of the government covered up the existence of extraterrestrial life, that aliens had built Native American settlements in New Mexico (ugh, white privilege much?), or that vampires and death-foretelling psychics and limb-lengthening serial killers all exist — though conveniently, the supernatural beings never seemed to encounter each other — his anti-government paranoia (despite his position as a federal officer) and skepticism of science came across as being “cool,” because his extremism was a rare point of view at the time, and because the show nearly always made him right.

Mulder was one of the series’ two leads, but it’s his starry-eyed righteousness and wounded plea for justice that has proved enduring and influential. What was the point, after all, of Scully’s scientific and medical training if none of that knowledge ever proved applicable to (the show’s) reality? That was The X-Files’ sleight of hand: its peppering of scientific jargon gave the show a patina of educated respectability, but scientific knowledge was often derided as a crude and inadequate forensic tool. The greater value lay in Mulder’s leaps of faith — or, to use today’s parlance, his sense of “truthiness.”

But in the twenty years since the show’s premiere, extremism — the rejection of mainstream news, science, and politics — has become its own institution. With the aid of the Internet, birthers, truthers, and vaccine skeptics have joined the UFO believers in establishing their own insular networks of news outlets, social gatherings, political activism. As if the alien bounty hunters with the Icepick of Death had returned to Earth, the Mulders have proliferated in number and influence; they now peddle blogs and endorsement deals and segments on The Dr. Oz Show. Glenn Beck is just another Mulder with a chalkboard, crocodile tears, and a get-rich scheme.

So when Fox Mulder was reincarnated on Fox News, it was like discovering that my first love, who had seemed so sophisticated and had taught me so much about myself and the world, was actually a skeevy, none-too-bright loser. Worse, he wasn’t just spouting stories about ghosts and extraterrestrial visitors — unlikely but credible possibilities and harmless to entertain — or even about fantastical but actual mysteries like the Bo Xilai case. No, he was foaming at the mouth about how 9/11 was an inside job. Wake up, sheeple!

Especially since 2009, we’ve seen the ugly destinations anti-government hysteria and science denial have taken us. News coverage of the Bin Laden assassination and the Boston Marathon bombings were immediately hounded by offensive rumors of their having been staged. The rise of the tea party helped bolster the careers of gravely misinformed politicians like Michele Bachmann, who publicly stated that HPV vaccines cause “mental retardation,” and Marco Rubio, a climate-change denier who sits on the Senate Science Committee.

So I’ll be eternally grateful to The X-Files for getting me through my awkward teen years, but I can’t help being angry at the show today for helping glamorize and mainstream real-life extremists, endowing them with a righteousness — not to mention a place at my Thanksgiving table — they don’t deserve.

My eventual conversion against The X-Files speaks to a larger truth about the show: its unique political vulnerability. Since 2001, right before its last season, creator Chris Carter has been saying that 9/11 killed the show. The War on Terror told us that aliens were already among us, and they wished us harm — we just called them “terrorists.” When the “9/12” moment came, people needed to put faith in their government again, not question its motives.

But the recent ascent of anti-government and anti-science politicians to Congress — not to mention the ongoing spread of militias and measles — makes The X-Files’ willingness to contemplate, even glorify, extremist views feel misguidedly idealistic at best, and disingenuously destructive at worst.

As TV characters are fond of saying in rueful moments, things didn’t have to be this way. Mulder had other ideals — law and order, citizens’ privacy, government transparency — and it so happens that at this point in time, the extremists are having their moment and retroactively destroying my love for the series.

But there may be an epilogue to my lost fandom. The perception of many artistic works depends greatly on each generation’s priorities and occupations, and so my feelings on The X-Files may change yet. Bradley Manning, Julian Assange, and Edward Snowden ignited a national discussion about government secrets. Whether Manning and Snowden are heroes or traitors, surveillance is easier than ever to both enact and hack. Thus the disclosure of state secrets — and the ethics thereof — is likely to be an important subject for years to come.

Not so coincidentally, Carter is reportedly developing a series for AMC that explores exactly these topics. In another ten or twenty years’ time, then, Mulder might lose his tin-foil hat and look like pop culture’s greatest whistleblower. Transparency — so revered in peacetime, so easily and irreparably abandoned during war — might be the spark to help me fall back in love with The X-Files one day.

Inkoo Kang is a freelance film and television critic.