I remember exactly where I was when I learned of the deaths of Kurt Cobain, Princess Di, and Amy Winehouse.* The same is true with regard to the sad news of a number of more recent celebrity deaths, when I have been positioned in front of a computer screen, watching Twitter reactions flash before me that add an additional layer to my emotions. But somehow I have no recollection of where I was or what I was doing when, twenty years ago, I heard the news that River Phoenix had died.

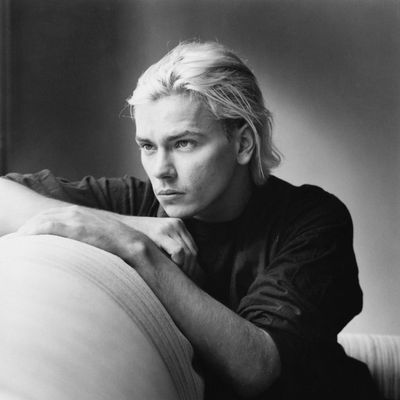

I was, indisputably, a fan. I adored him in Stand by Me, which I watched repeatedly on VHS. I pasted his face to my lime-green bedroom walls, tearing the pictures out of fan magazines. In the video store, I’d try to convince my parents to let me rent the R-rated movie A Night in the Life of Jimmy Reardon, which featured teenage River as the star — it looked so good! (Later, I learned it was not.) River was this beautiful golden boy with floppy golden hair, the James Dean look-alike, the risk-taker, the indie musician, the environmentalist, the vegan, the Oscar-nominated talent, the badass with the cool name and the big heart. [See our River Phoenix photo gallery here.] Above all, he had potential. He seemed to combine so much of the past, along with elements of a future we were just getting around to thinking about. It wasn’t because of River that I started an environmental club at my high school, exactly, but without him, I’m not sure that would have happened. And then he was gone.

Last Night at the Viper Room: River Phoenix and the Hollywood He Left Behind is a timely biographical release from Gavin Edwards, who’s also a Rolling Stone contributing editor. Even if, like me, you don’t remember where you were when River died, you can probably recall the story of how it happened. It was in the early hours of October 31, 1993. Having consumed a speedball of cocaine and heroin at the Viper Room, the West Hollywood Club owned at the time by Johnny Depp, River collapsed on the sidewalk outside, surrounded by his girlfriend, the actress Samantha Mathis; younger sister Rain Phoenix; and his younger brother, Joaquin (who was better known then by the name Leaf). In a matter of an hour, he would be pronounced dead. Had he survived, he’d now be 43 years old — seven years younger than Depp and Brad Pitt, four years older than Leonardo DiCaprio — and, one imagines, doing something interesting with his life: touring with his band, breaking new acting ground, directing independent movies, perhaps running a successful charity organization. Being a star. Instead, the way River’s life ends is how the book begins, in an introduction that plays the actor’s last scenes before rewinding again to the first, because of all the things we remember about River Phoenix’s too-short life now, the most immediate is his death (even if we can’t remember where we were when we heard about it).

Celebrities who die young tend to claim a certain part of our brains, remaining there, perpetually youthful, forever tragic, containing their warning lessons to others and imbued with a question of what if? If it had gone differently, if the tragedy had been averted, if the call had been made just a bit sooner, who might they have become? But River Phoenix, who died just five months before Kurt Cobain shot himself, seems to cast a fainter shadow than the others. Maybe it’s because he was only 23 — not even old enough to be a part of the 27 Club, and, the bulk of his time spent acting, not that caliber of musician anyway. Possibly, his death, caused by a mistake, an overdose when he seemed on the verge of getting clean after a spate of attempted interventions by friends and family, doesn’t come with enough internal horror (compared, say, to Cobain’s; certainly, it’s horrible enough). “Apparently the nineties had room for only one angel-faced blond boy, too pained by the world to live in it,” writes Edwards.

But River didn’t want to die, as Depp told people afterwards. He arrived that night at the Viper Room with his guitar, wanting to play. “That’s not an unhappy kid,” said Depp. It could be, Edwards posits, that his filmography wasn’t powerful enough, his roles too scattered in the wide spaces between The Mosquito Coast, My Own Private Idaho, and Sneakers (he made thirteen movies in all, far more than James Dean did). Maybe it was too many ensemble casts or bit parts, not enough starring roles. Whatever the case, in 1993 we didn’t think we’d forget. “When River died, it was generally assumed that he would become the ‘vegan James Dean,’” explains Edwards, “a star even better remembered in death than in life, a potent symbol of youthful talent and beauty snuffed out at an early age. Instead, he faded in people’s memories.”

The anniversary of a death is a handy peg for the release of any celebrity biography, but Edwards’s book, which broaches the question of why we’ve forgotten as well as painting a vivid picture of River’s life, and, more broadly, his era, reaches well beyond that day alone. This is a book about a particular time, and it beautifully captures the weird Zeitgeist of the eighties and early nineties in a way that will remind those of us who were growing up at the time of not only River Phoenix, but also of ourselves at a younger age. Names checked and touchstone events cited: Ione Skye, the heyday of Alex P. Keaton, chubby Jerry O’Connell, ABC After-School Specials, the casting of Dead Poets Society, Anthony Kiedis, the first Lollapalooza, the year that Sundance really became something, Sassy magazine?

The six-part book consists of bite-size, varied chapters, some as short as a paragraph, that shift from well-researched biographical history to pictures of “Young Hollywood” (glimpses at the various progressions of River’s cohort before they became household names) to scenes from movies River starred in that cause deep emotional reverberations in hindsight (Edwards calls these “Echos”). Overall, it’s a Who’s Who of Back When, the “characters” — Martha Plimpton, Ethan Hawke, Christian Slater, Keanu Reeves, Winona Ryder, Leonardo DiCaprio (who almost met River at a party on the night he died), Wil Wheaton, the two Coreys, the Butthole Surfers, Depp, Pitt, and so forth — and scenes woven throughout offering a pop-cultural retrospective that feels comfortably nostalgic, highly entertaining, and sometimes heartbreaking.

Edwards is clearly sympathetic to his subject, whose original name was “River Jude Bottom” until his father chose “Phoenix” as their last name to represent a new start. Things I didn’t learn from my Bop magazines back in the eighties: River (a name inspired by the book Siddhartha) was the eldest son of hippies who joined the Children of God cult; later, he told friends he’d been sexually active, per the religion’s “doctrine,” at the age of 4; he was thought to be dyslexic; his large family relied on him as the breadwinner; he’d tell people he wanted to be famous so he could take care of his parents and brothers and sisters. I didn’t know that he would allow the characters he played to possess him fully and then often have trouble escaping them. And I still don’t remember where I was when I heard that he’d died, but Edwards’s book can’t answer that question. Nor can it answer — it can only speculate — whether River Phoenix paved the way for actors like Leonardo DiCaprio, who “played so many parts that River originally intended to do, it’s hard not to wonder which roles River might have beaten him out for, had he stayed alive and healthy.”

Twenty years on, questions of “Who could have prevented this tragedy?” and “Why did this happen?” have been replaced by newer tragedies, and maybe, older questions. Unlike Cobain, River was oddly relatable given his celebrity stature, though he was also an outlier in his time, not grunge, not yet a hipster, possessing more earnest emotion and raw talent than attitude as well as a barely shielded emotional pain that surely led to his drug and alcohol abuse. Perhaps his death has faded in our collective memory because we’ve moved on ourselves, but the latent potential he still symbolizes returned to me in waves upon reading Edwards’s book. Who would this 23-year-old boy on the cusp of manhood have become? Sadly, we’ll never know. Last Night at the Viper Room, however, is a reminder of who we all were then, and what we lost when he died.

* High school debate tournament, college bar, East Village Mexican restaurant