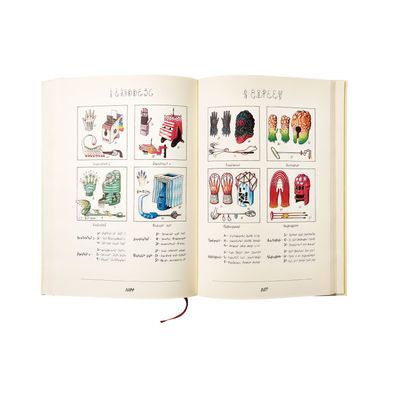

In 1981, a 31-year-old artist named Luigi Serafini published a very large, very peculiar book called the Codex Seraphinianus. It’s liberally illustrated with pen-and-ink drawings finished with precise colored penciling. Many pages show fantastical scenes, rows of small objects in what seem to be taxonomies, or explanatory graphics. The text, though, is where it goes totally around the bend: It’s written in an untranslated language of vaguely cursive, highly mannered loops, squiggles, and dots. Nobody (except Serafini, presumably) knows what it means, and he’s cagey. In 2009, he semi-explained it thus in a lecture: “The book creates a feeling of illiteracy which, in turn, encourages imagination, like children seeing a book: They cannot yet read it, but they realize that it must make sense (and that it does in fact make sense to grown-ups) and imagine what its meaning must be.”

That has not stopped a variety of grown-ups from trying to figure it out. An underground following has sprung up—copies of the first printing sell for several thousand dollars—and next week, Rizzoli brings the Codex back into print at a mere $125. Among its enthusiasts are Italo Calvino (whose preface to one edition offered that Serafini “believes in the continuity and permeability of all areas of existence” and compared him to Ovid) and the writer Justin Taylor, who elaborated on the book’s mystery in The Believer a few years ago and arranged for the translation of Calvino’s essay into English.

So what the hell does this thing say? There is speculation all over the Internet, the consensus being that the glyphs are neither a pure letter-by-letter cryptogram nor a syllable-based system but something in between. Most “readers” agree that it does translate into actual language rather than gibberish. A Bulgarian linguist has figured out the distinctive code of the page numbers. One site devoted to the Codex claims that the book contains several Rosetta stones—but that they simply lead translators from Serafini’s glyphs into another weird language. Then again, that site also suggests that the author intends us to communicate with actual aliens.

The Rizzoli edition has a booklet tucked inside the back cover tantalizingly called “Decodex” and containing text in English and several other (familiar) tongues, but it doesn’t do much decoding. Serafini did offer this clue, in that speech a few years back: “The writing of the Codex is a writing, not a language, although it conveys the impression of being one. It looks like it means something, but it does not.” But of course that may be one giant red herring of misdirection, and maybe that’s the book’s point. Philologists can take their best shots; stoners can spark up; and the rest of us can simply ride along, appreciating the visuals. Caveat translator.

*This article originally appeared in the October 28, 2013 issue of New York Magazine.