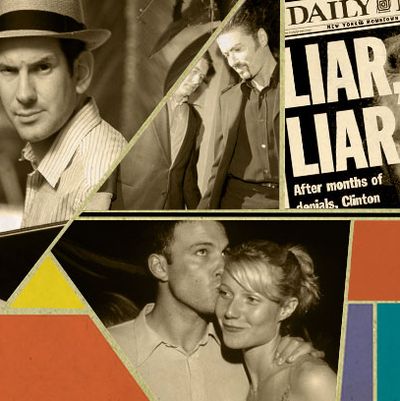

The gossip industry had a busy 1998. George Michael, who had yet to come out as gay, was arrested for “engaging in a lewd act” with a man in a public restroom in a Beverly Hills park. Maxim staple Carmen Electra and basketball player Dennis Rodman got married and divorced within a span of nine days (beating out by 72 hours the other lightning-quick union of the year: actress Catherine Oxenberg and movie mogul Robert Evans). Gwyneth Paltrow jettisoned Brad Pitt and started dating Ben Affleck. And there was that whole presidential thing going on. Quelle horreur! Le scandale! I was a long-time deputy editor in the New York Post’s infamous “Page Six” section, and looking back at how my peers and I covered gossip in the decade that followed, I see just how much has changed in how we track stories, what stories get tracked, and how readers learn about them. As part of Vulture’s weeklong look at fame in 1998, here’s how the gossip game has metamorphosed — and one way it has stayed the same.

Social media has increasingly cut out the middleman.

In 1998, cellphones were rare, the few who carried a camera or camcorder would not have been able to share pictures or videos with any kind of haste (YouTube and Facebook were years away), and even e-mail was a little-used tool. Yes, Matt Drudge was rambling around on that shiny new thing that Al Gore claimed to have invented, but most gossip columnists were still dependent on a fax machine, a landline, and a strong liver.

Celebrities can now bypass all the press outlets and instead rant, rave, and drop news (e.g., “IM HAVING A BABY!” or the more subtle method of an Instagram shot of an engagement ring on a finger to denote an affianced situation) on their own Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, or blog. And why wouldn’t celebrities go that route? The news will get picked up anyhow and the buzz will drive traffic back to their official website, boosting visitors/followers, which in this day and age directly translates into dollars (so-and-so has 2 million Twitter followers? Get her a Pantene contract, stat! She’s huge with the “young people!”), or, in the case of social-media star Alec Baldwin, his own (quickly potentially canceled) TV show.

A new breed of gossip outlets has emerged.

Despite social media’s rise since 1998, there’s still a demand for traditional ways to consume gossip. But the names and outlets have changed drastically. Scandals and mishaps were covered by an elite guard consisting of Army Archerd of Variety, George Christy of The Hollywood Reporter, Rush & Molloy and Mitchell Fink of the New York Daily News, Beth Landman at New York magazine’s Intelligencer. and even the august New York Times had the “non gossip, gossip column” Public Lives. All were in competition with us at the New York Post, which dominated the sphere with three gossip columnists — Neal Travis, Cindy Adams, and Liz Smith — as well as my former employer, “Page Six,” the heavyweight column run by bon vivant Richard Johnson.

Sure, there were celebrity magazines also covering the foibles of the rich and famous — but not nearly as many as there are now. US Weekly was US monthly and a news magazine, the European invasion in the form of the Bauer titles (In Touch, Life & Style) and OK! was years away, and People magazine had yet to become the favorite drop-off slot for publicists and their clients who just wanted to tell “their side of the story.” Back then, People was still running lengthier, reported, in-depth, newsy articles, as well as not-so-nice pieces on celebrities from their detractors (sample headline: “LeAnn Rimes ‘Manipulative’: Stepmom”) — something that would never happen in the touchy-feely “we celebrate celebrities” People of today. The National Enquirer was given a run for its money by sister publication Star – which was, back before Bonnie Fuller and David Pecker, a downmarket, non-glossy, hard-hitting tabloid … with over 2 million readers.

Now, the dinosaurs of the industry — Mitchell Fink, Beth Landman, and Liz Smith — have been put out to pasture. Neal Travis and Army Archerd passed away. First Rush and then Molloy retired from gossip — and even Richard Johnson left “Page Six” (to eventually come back to the Post with his own column). And a horde of gossip-chasing entertainment websites have since sprouted up — TMZ, most notably — updating news not just every hour but sometimes every minute, ensuring that every iota of celebrity is covered from every angle. If something is happening and someone is on hand to witness it, you can be assured of finding out about it almost immediately.

There’s a different breed of boldfaced names.

The quality of celebrity has also drastically changed. Movie stars thought television shows were beneath them — and television stars were dying to be movie stars. In 1998, the only big reality show was MTV’s The Real World — and everyone thought that was coming to an end. Paris Hilton had yet to drop out of high school to focus on her career of dancing on banquet tables and flashing her privates to unsuspecting club goers. The invasive species of paparazzi was contained to one loathsome specimen: Steve Sands.

Today, there are hordes of paparazzi, and more often than not, that big shot will consist of a reality-show star who most likely has filmed and released his or her own sex tape in order to become famous. Movie stars are still movie stars, but TV — which multiplied from the network and a few cable stations to thousands — is where the big money and fame is at. Actors who once turned their nose up at a (scripted) television show are now vying for their own reality show.

What may never change: the tit-for-tat nature of the gossip game.

“You want the big scoop on my movie-star client? Okay, but you’ll have to put in a mention of my lousy watchmaker client.” This tried-and-true system that is still in place to this day. The more space and reach your publication had, the more favors you could do — a necessary evil in order to ensure that when the big story came around, it would be yours. Five lousy watch/dentist/shoe sightings equaled one great scoop.

Naturally, there was a dark side. Unencumbered by competition of the nameless, faceless minions of the Internet who constantly churn out celebrity news, the gossip columnists of the day were, more or less, stars themselves. As the gatekeepers to popular press outlets, the columnists were there to be wooed, schmoozed, and feted. Because if an event happened and it wasn’t in the press and nobody knew about it, did it really happen at all? Gifts were sent openly and sometimes not so openly. For all those outwardly pious people at the highbrow publications, there were always discreet deliveries at the person’s home or dry cleaners. Dinners and trips were paid for, cars were loaned gratis, clothing was gifted, and the best seats at a restaurant or theater were donated. In one instance, I even heard of an apartment that was handed out at a rate way below market to a (now-deceased) columnist by one press-loving real estate tycoon. Everyone behaved as if they were a member of the Hollywood Foreign Press … or a member of Hollywood itself. The behavior got so egregious, scandals ensued. In 2003, George Christie was eventually fired for his graft-grabbing, and in 2006, “Page Six” had its own issues spawning from a freelancer attempting to extort a billionaire.

Hilariously, determined organizations like Scientology and Whitney Houston fan groups could shut an old-school gossip column down for days simply by getting their devoted followers to clog the fax and phone lines when something disagreeable was written that they disagreed with. To this day, I get hives when I type the words “Scientology is a cult!” or “Whitney Houston does drugs!” And with that, I’m off to consult with my allergist.

Paula Froelich, the former deputy editor at the New York Post’s “Page Six,” is a novelist as well as a world traveler who also exists on on Twitter.