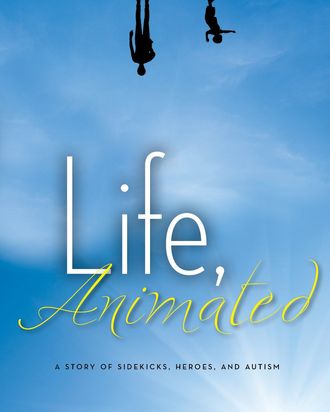

In 1993, Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Ron Suskind moved to Washington, DC with his wife Cornelia and sons Walter, 5, and Owen, 2, to embark on his career as a national-affairs reporter for The Wall Street Journal. Soon after the move, Owen stopped speaking. Distant and agitated — he would soon be diagnosed with regressive autism — Owen sought comfort in Disney movie classics. The Suskinds would come to embrace this focus as his special affinity and Ron would eventually write about it in his new book Life, Animated (out this week), a departure from the works on presidents and power for which Suskind is well-known. Vulture spoke to him about the process.

Why Disney?

The early ‘90s were a Disney renaissance. Every kid was watching the mermaid, the genie, and the lion. Add to that the [widespread use] of the VCR in the late ‘80s. Movie obsessives could dig into their favorite narratives: those that reflected how they felt. Multiply that by 20 for a kid like Owen.

So he memorized all of them?

Oh yeah. When we decided to move forward with the book — it was a family decision — my agent pointed out that almost every word Owen says is licensed by a multinational corporation. That’s why I went to Disney as the publisher. Thankfully, they agreed to zero influence over the content.

You describe your family as “using a story to get what it needs.” Did you always feel like you were in control?

Every autistic spectrum kid has an affinity – Disney, anime, maps, train schedules. Plenty of therapists argued, and still do, that these affinities are something to be reduced, even cut off. Early on, we tried using Disney as a behavior tool. You know, if you want to watch your movies, you’re going have to walk over hot coals first. Owen would buckle down, and try to do the thing we asked. But eventually, he would flag. It was like we’d cut off his source of nourishment.

So then you took the opposite approach.

We decided to let Owen take the lead. We started putting on voices and acting out the scenes with him in front of the TV. It was joyous. Owen started to give us little clues — this is really that, this attaches to this. On Walter’s tenth birthday, when Owen was six, he finally spoke: “Walter doesn’t want to grow up, like Mowgli and Peter Pan.” It was his first complete sentence in four years. At that point we realized we were going to have to live inside a Disney movie.

When Owen starts rewriting Disney scripts, it’s hard to ignore that he’s a son of writers.

Watching Aladdin, Owen bonded with Jafar’s sidekick Iago. But once he could understand that Iago was a bad guy, he had a dilemma. How could he be friendly towards a bad guy? So he conceived of a narrative solution. He came up with the line, “Anyone with that strong a sense of humor has to have some good in him,” and added a new scene in which Iago frees Aladdin from jail, saving the day. Ask him to write about Lincoln for a school assignment, you’d get nothing. Here, it was lucid.

I’m not the first person to ask you questions about Owen, who’s now 21 — questions that would be tricky for him to answer in an interview, never mind in a public forum. Are you comfortable seeing him in the spotlight?

So far, he’s actually been very comfortable with large groups — signing books, engaging with readers. He doesn’t sense potential disasters when he gets on a stage. He doesn’t look right or left for refutation or affirmation.

What are your hopes for the public response?

These days, people have a million ways to self-nourish. In some ways, Owen, with all of his burdens, is just an extreme case of self-direction, and we want to draw attention to this fact. Painting Disney characters, and writing new stories for them, he’s found his bliss. After letting him communicate on his own terms, we’re watching him start to more fully live a life. Ideally, this book will reverse the telescope. Over the past year, autism researchers have told us, “Thanks to your 20-year, familial investigation, we’re seeing these affinities in a new way.”

You started reporting A Hope in the Unseen at Ballou High School in one of Washington D.C.’s toughest neighborhoods right around the time Owen retreated into himself, at age three. How did the situation at home affect your journalistic perspective?

Suddenly, I was questioning my trained omniscience — the kind of thing that journalists get paid for. You know, we sum up quickly, and our subjects can become stock characters: inner-city black male versus fatigued teacher, you know? When people stared at these students, passing judgement, I couldn’t help but think, ‘This is the way people will stare at my son.’

Early on in the book you insist, “The last thing I would ever want to do is sentimentalize my own son.” How did you avoid that trap?

Owen is literal to a fault. That’s how he approaches Disney movies and their moral precepts — anyone can be a hero, beauty lies within, love lasts forever. Society teaches us to be dismissive of these tropes, but Owen doesn’t register these supposed-tos. In fact, like a lot of autistic kids, his desire to feel the emergence of the hero, to experience beauty and love, is extremely acute. This motivates him, and his hard work pays off! He’s had a girlfriend for the last two years. They’re extremely attentive to each other and, of course, they’re always honest. They can’t be otherwise.

So these moral precepts are powerful catalysts.

Owen gives depth to these stories, out of necessity. Imagine if you had to figure everything out through the lense of the 50 animated movies since Snow White. There’s a moment in the book when Owen and his friend Molly sing a duet at Disney Club — the group Owen started at his college program to watch and discuss Disney movies with other spectrum kids. Molly sings, “And for once it might be grand … ” and Owen sings back, “To have someone understand … ” and then all of the kids sing in unison, “We want so much more than they’ve got planned.” That’s from Beauty and the Beast. It was also almost the title for the book.

Oh really?

Cornelia was really pushing for it. I mean, I want so much more than they’ve got planned. That’s the real stuff right there. I want more than the world expects of me, and I’m going to find a way to get it. Because that’s what Owen does. In his own quiet way, he is quite ferocious.