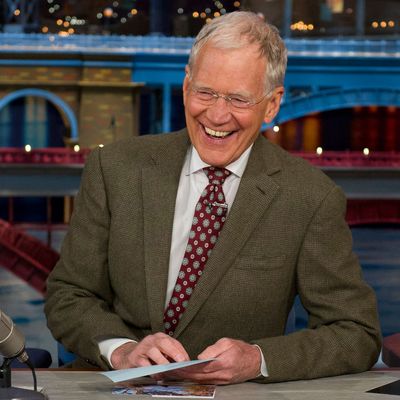

This post originally ran in April 2014, when David Letterman announced his retirement. We are rerunning a slightly updated version with David Letterman hosting his last Late Show tonight.

From the very first episode of his NBC show, David Letterman, who will retire tonight, let you know what he was about — and that it damn sure wasn’t the Usual.

When the host’s producer got caught within camera range onstage and crawled on all fours into the wings, Letterman called attention to him rather than ignore him. “Nothing left to chance here, you know?” he said. “Well, by this point, you’re asking yourself what else this show has,” he went on, and waited for an out-of-context game-show-style buzzer to sound — BLAAAAAP! — and crowed, “Well, we have one of those!” His inaugural guest was Bill Murray, who at that point was to TV sketch comedy and film what Letterman was to talk shows: enthusiastic yet deeply self-aware, exposing the inner workings of comedy even as he made the comedy work. Murray sat down and then suddenly stood up, and in that simultaneously facetious and sincere way of his, demanded that the audience stand for Dave. Then he quickly sat down again and deadpanned, “I missed the first part of the show, by the way. What happened?”

“What happened?” That was what you asked fellow fans if you showed up at their houses or dorm rooms a half-hour into NBC’s Late Night With David Letterman, or its successor, CBS’s The Late Show. “What happened?” was also what you asked if you’d seen every second. During the first decade of its existence on NBC, and sporadically afterward on CBS, he and his writers specialized in comedy that was also “comedy.” Letterman’s deconstructionist, at times borderline Cubist style made you laugh by mocking the very idea of a stranger needing to make you laugh; my friend Ken Cancelosi calls it “The Marcel Duchamp approach to late-night.” Letterman’s sensibility had its roots in a post-World War II school of university-educated smartass comedy, which also birthed such institutions as Mad magazine, Monty Python, Second City, National Lampoon, Saturday Night Live, the 1970s meta-comedy movement that gave us Andy Kaufman and Albert Brooks, and pretty much every moment of Bill Murray’s early career. (Writing about Murray’s performance in Ghostbusters, The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael wrote: “He’s always an onlooker; he won’t commit himself even to being in the movie.” It’s no coincidence he became David Letterman’s good-luck charm, a go-to guest who inaugurated the CBS version of the show as well.)

On Letterman’s late-night shows — and on the short-lived 1980 daytime program that unwittingly served as his comedy workshop — nearly everything was enclosed by cartoon quotation marks. Sometimes the quotation marks were in quotation marks, too. Letterman was the first late-night host to take most of his cues from TV sketch comedy pioneer Ernie Kovacs rather than from vaudeville or radio. (In retrospect, it’s not surprising that he championed Andy Kaufman, the Ernie Kovacs of stand-up comedy, even when the industry had written him off as a nuisance and made a minor celebrity of underground comics writer Harvey Pekar.)

The real-time creation of a talk show was every Letterman broadcast’s true subject, and the segments and guests and musical acts were folded into it. He’d wander off down the hallway or out onto the street in long, unbroken takes, with missed cues and stumbles adding laughs, and interview tourists, or cops, or Rupert Jee, the owner of the Hello Deli. His nightly Top 10 lists, often the highlight of a given show, were funny not just because some of the one-liners landed but because many more did not, and because Letterman seemed vaguely put-out by having to read good and bad material alike, he behaved as if he couldn’t wait to plow through it all and go home and smoke a cigar and go to bed.

He was especially uncomfortable during interviews; if they weren’t with young and flirty women, pop-culture giants like Dennis Hopper, or heads of state like former president Jimmy Carter, you could feel him mentally check out. He radiated dislike for the whole chatty ritual as hallowed by TV history and refined by his predecessors, including the great Johnny Carson, who tapped him as a regular co-host of The Tonight Show and groomed him as his rightful heir. How sincere, or insincere, was Letterman’s grouch act? He constantly struck a tone that fell somewhere between “old-fashioned showbiz enthusiasm” and “misanthrope performing at gunpoint.” That these poles of the performance spectrum are normally irreconcilable added to the mystery of Letterman. After a while, he became known as a kind of anti-interviewer who was most exciting to watch when his guests weren’t digging the ritual either. (See Vulture’s 10 Guests Who Trolled David Letterman.)

Many of his segments, particularly cooking segments and friendly “competitions” with guests, felt like parodies of segments that other programs would play straight. Letterman switch-hit between seeming to genuinely enjoy the company of others and fussing or grumbling about having to be there at all. A lot of the humor stemmed from an awareness of the suspension of disbelief that talk shows usually required of audiences: for instance, the idea that guests were just talking spontaneously, as opposed to regurgitating comments they made during backstage pre-show interviews, or that the talk show itself was a self-enclosed universe rather than a televised property that just happened to take place on the soundstage operated by a broadcast network (NBC or CBS) that was owned by an aloof, middlebrow, or sinister conglomerate (GE or Viacom). He made sport of his bosses, and it wasn’t that clawless kitty-cat pantomime you saw enacted on other talk shows where hosts beefed with the suits. And he was genuinely weird. Random. He’d do stuff like attach a tiny camera to a monkey on roller skates, or drop things off the roof of the studio building — the sort of shenanigans that his archrival Jay Leno, who stole the coveted Tonight show out from under him in 1993, would’ve been mocked for doing, because he lacked Letterman’s multiple layers of self-awareness: that bizarre mix of a permanent wink and half-sneer near that said “I’m just kidding, folks — I don’t hate you, or myself, maybe.”

“If what you’ve done is stupid, but it works,” he once said, “then it really isn’t all that stupid.” That’s the most charming way of saying the ends justify the means that I’ve ever come across.

If none of the above sounds revolutionary to you, or in any way unusual, it’s because you were born a while after Letterman became a thing. After a decade or so, his innovations and tweaks and bizarre tics had been absorbed into comedy’s circulatory system, nourishing the next two generations of comedy performers and writers (including Conan O’Brien who went on to work on The Simpsons). This is how it happens: What was once shocking becomes the norm. Mainstream. The usual.

Now he’s just an old man doing meta-humor for the benefit of your mom and dad — in his terrific 2009 Letterman profile for New York, Peter W. Kaplan called Dave “the last grown-up on network television” — and at one point, he became a dirty old man, when he got embroiled in a sex scandal involving young female staffers (depressing development, that). He’s marginally hipper than Leno was, but maybe you never watched either of them, and maybe you don’t watch any of his successors anyway — at least not in the way that people used to watch late-night shows, by actually sitting down when they started and viewing all 60 minutes, minus ads. Whether the programs air during the day or at night, and whether they’re hosted by Jon Stewart, Chelsea Handler, Craig Ferguson, Jimmy Kimmel, Conan O’Brien, Ellen DeGeneres, Arsenio Hall, or the new host of Tonight, Jimmy Fallon, the primary function of all talk and comedy programs is to supply disconnected bits of entertainment to the internet. Everybody’s working for YouTube now, whether they realize it or not. That’s not a good thing or a bad thing, just a thing, but it gets at the fragmentation and evolution that’s rendered not just Leno but pretty much everybody culturally marginal. (And we haven’t even gotten into the issue of whether we need yet another white dude hosting one of these shows, or whether we need another one of these shows, period.)

Letterman’s artistic achievements are substantial, though, and nobody can take them away from him, just as nobody can take the first ten or so years of The Simpsons away from Matt Groening, or the first five seasons of SNL away from Lorne Michaels, or the the years 1986—1992 away from Spy magazine. The struggle to take over The Tonight Show alone deserves a fat footnote in the story of TV in the ’90s. It was one of the first truly inside-showbiz stories to spill out of the trade papers and the New York Times and enter mainstream gossip, alongside who was sleeping with whom. The whole sorry affair was chronicled in Bill Carter’s book The Late Shift, which (incredibly) became a top-of-the-line HBO film, with John Michael Higgins as Letterman, Daniel Roebuck as Leno, Kathy Bates as Leno’s profane and ultimately self-immolating manager Helen Kushnick, and longtime Carson impressionist Rich Little as Carson. I know showbiz journalists and a good many regular viewers who can recite every twist in Carter’s narrative the way Greek children used to be able to recite the highlights of the Peloponnesian war. (Remember when Leno hid in a closet and eavesdropped on his bosses?)

There was no way Letterman could’ve gotten that job, really; he would’ve rocked Johnny’s boat too hard, and probably driven away viewers. He pulled ahead of Leno in the Nielsens for a while, and then Hugh Grant decided to go on Leno and make his big sex scandal apology, and from that point on, Leno dominated the late-night ratings and NBC looked as if it had made the smart play in kicking Letterman to the curb. But I wonder if, in quiet moments, Leno feels as though he won the battle to succeed Carson but ultimately lost the pop-culture war? He got the plum gig, but Letterman got the cachet.

“I’m just trying to make a smudge on the collective unconscious,” Letterman once said. Mission accomplished.

* This piece previously stated that Conan wrote for Letterman. He did not.