Three years ago, when I met Justin Bieber, he gave me a stuffed yellow bird with googly eyes, a rhinestone-studded black wineglass with a candle inside, and a card signed “Love, Justin,” with a heart over the i. We were in a hilariously gigantic suite on top of The Four Seasons Hotel in Beverly Hills, and he was a short fellow, barely over five feet tall. At the time, with the imminent release of the propaganda film Never Say Never, which would become the highest-grossing concert film in history, Bieber Fever was reaching its shrillest pitch, but the boy himself, approaching his 17th birthday, seemed unfazed. The gifts he brought were an apology of sorts, because his team had postponed our interview for Rolling Stone several times, and he declared, “We bought those presents downstairs, in the lobby!” with a grin, as if an impromptu gift was better than a thoughtful one.

As we spoke, Bieber struck me as a precocious kid, talking about mastering the Rubik’s Cube and spewing forth lines memorized from rap songs and Will Ferrell comedies. “Justin is just freakishly good at everything he did or does,” said his mother, Pattie Mallette, a thoughtful, soft-spoken woman so tiny she stood at least a head shorter than her son. “At 1 year old, he could carry on a conversation. At 2, he was having full conversations on the phone. He played all-star travel soccer, all-star travel hockey, was chess and golf champion of our region—and he’s amazing at Hacky Sack.” Bieber’s phone buzzed with a call from Selena Gomez, whom he had just started dating—and whom, in a weird moment, a member of his entourage, led by his charismatic, self-mythologizing manager Scooter Braun, asked me not to mention, lest the Beliebers lose faith he was a gift from God exclusively for them—but Bieber said, in what felt like an act of superhuman control, “I’ll talk to her later. I’mma finish this.”

Despite possessing the elements for youthful renown—developmentally advanced and so unafraid of life that even Hacky Sack was no match—Bieber, like most kids, didn’t seem to enjoy the theater of fame. He wanted to sing, dance, record, and perform for wailing, garment-rending fans (always, when Bieber was in public, a long, high-pitched sound, like a subway squealing into a station, trailed behind him), but he was somewhat creeped out by intrusive adults, and when I informed him the interview was over, he literally jumped out of his seat and shouted, “We’re done? Swag!” He didn’t love journalists and loathed pictures. “I hate paparazzi,” he said, shaking his head. “They’re like stalkers with a camera. How come if someone’s following you, it’s a crime, but if they’re following you with a camera, it’s just okay?”

Despite these predilections, notoriety had descended on Bieber in a manner that 99.999999 percent of the Earth’s inhabitants will never experience. Fans of all ages, “including moms,” the bodyguard told me, were desperate to deflower the boy—if, indeed, there was flower. (The word at the time was that Bieber’s entourage, or “band of brothers,” as they called themselves, discouraged groupies but looked the other way during anonymous sexy chats on the computer at night.) Bringing up Bieber was his entourage’s calling, and they outlawed alcohol backstage at his shows, redirecting post-performance energy toward renting luxe, blingy cars in whatever city he found himself that evening. The boy passionately described the strengths of Ferraris, Lamborghinis, Bentleys, Porsches, and Range Rovers.

As I sat there with the little Bieber, the question of what he would become loomed large in my mind. Would he be a teen-pop casualty like Aaron Carter, or was he a value stock headed for superstardom? At the time, I would have put coin on No. 2. I didn’t think that Bieber would fly close to his idol, Michael Jackson, whom he brought up often—I breathed a sigh of relief that the boy would never have to decide whether to sleep over at Neverland—but imagined him as a pale version of Justin Timberlake, a peach-fuzzed post-R&B white boy who set out upon the world to de-nastify Bobby Brown for the Ohio crowd at a time when major male pop stars could be counted on one hand. There was a future in that.

Braun and the entourage agreed with my assessment, naturally, but the grimaces, the neurotic energy, and cries of “Justin is totally normal” with which they greeted this line of questioning showed their hand. There was perhaps no issue that consumed their psyches more than that of Bieber’s future and which way he would go. “Do I have to help Justin grow up, do I have to set boundaries, do I have to help him become a man?” Braun asked me, his voice rising passionately. “I think that’s 99 percent of my job. Justin is already talented—I can find records for him all day. No child star has ever lost as an adult because of their talent, ever. You can’t say, ‘Oh, their talent just disappeared when they hit 20.’ They always lose because of their personal life—drugs, alcohol—every single time. So I tell Justin, ‘The few exceptions just didn’t fall into that shit.’ ”

I clutched Bieber’s lobby-bought presents to my chest.

“It’s just not as hard as everyone thinks,” Braun said.

Wheee! There goes Bieber, adopting and then abandoning a pet monkey, pissing in a janitor’s mop bucket and yelling “Fuck Bill Clinton,” the pilots in his private plane hurriedly strapping on oxygen masks as he lights joint after joint in the cabin, far above the clouds. The explosion of his teenage energy over the past couple of years has been huge, and amusing, and ugly in parts—the obnoxious deposition tapes over an alleged bodyguard-paparazzo altercation, where he taunts a defense attorney with “Guess what? Guess what? I don’t recall,” and the recently released videos of his younger self telling racist jokes, with mention of the KKK—but always in line with the thinness of his emotional maturity. It’s a known known among people who work with famous people that famous people are psychologically stuck at the age they became famous, and Bieber is eternally 14. There he is, allegedly chucking eggs at the house of an annoying neighbor; tagging the sides of buildings other than the ones that international hotels, in their questionable wisdom, have expressly given him permission to tag; and hitting his own bodyguard in a snit, although the guy “did not retaliate or attempt to protect himself out of concerns for Bieber’s physical well-being.”

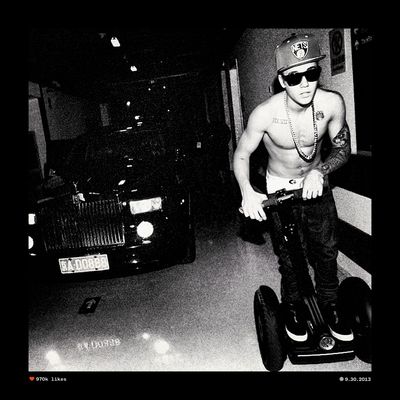

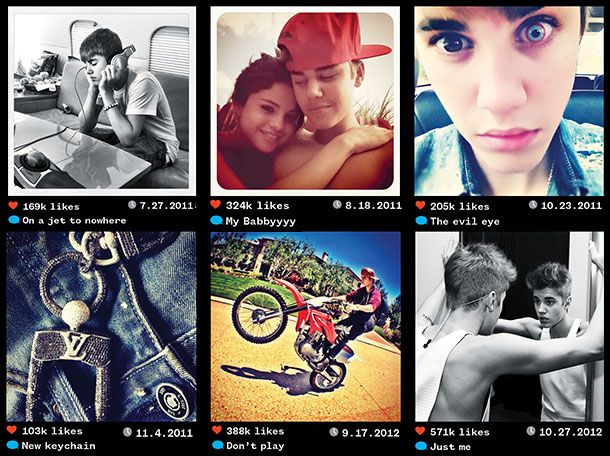

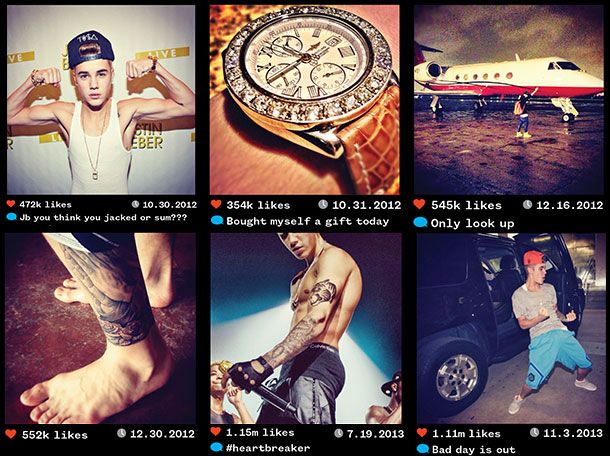

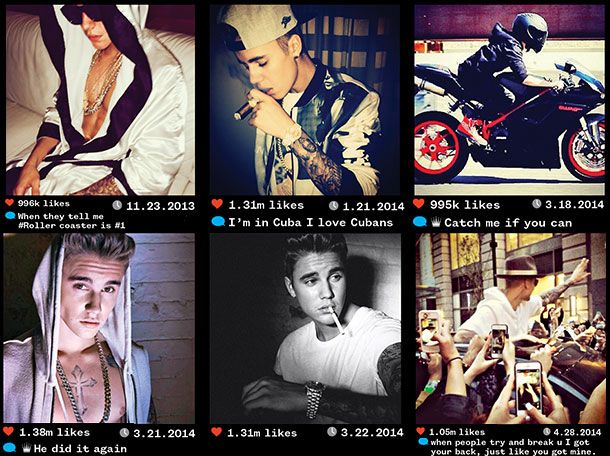

It may surprise you to know that, despite the saturation coverage of Bieber’s antics, he has not granted a real solo interview in almost two years, and won’t put out an album for a year. And yet you’re about to read a 5,200-word article on him, which may or may not be a colossal waste of your time. Through the images of him that have been generated by gossip magazines and those he has put out on social media, Bieber remains a powerful cultural figure and the “most scrutinized person on Earth,” as a business associate of his put it to me. The wider world may deem him a devil, or “Joffrey Bieber,” as he’s called on the internet, and when he last went on Saturday Night Live, several cast members reportedly considered him the world’s brattiest guest—and they know from bratty guests—but the enchantment of the Belieber fan base remains relatively intact. Signed to Island Def Jam, he has 52 million Twitter followers, more than anyone except Katy Perry, perhaps pop’s earliest adopter of social media. When Bieber Instagrams a picture, between 500,000 and a million fans “like” it within seconds (by contrast, President Obama’s photos on Instagram garner about 40,000 likes).

For the rest of us, it’s a show, vaudeville, and we’re still watching, captivated by who may emerge or simply irritated enough that we keep looking in that stuck-in-traffic-after-a-car-crash way. He’s little Mr. Big Man, the innocent boy turned de-virginator, master swordsman at a Brazilian brothel, double-sleeve-tattooed thug, gold-chain-bedecked hood. He sees himself as Brando, McQueen, Dean. We may see something different—a costume of machismo; a slip of a boy buffed up and doffing his shirt like a South Bronx stoopie in August; a white person fetishizing blackness with the laserlike focus of someone for whom “being down” is the most important thing in life—all of it, perhaps, a way of covering up and hiding so that we don’t find out what’s behind the curtain, in case there is nothing at all.

Bieber is an essential player, and beneficiary, of the low-culture fixation of the moment: whether child stars, those entitled, overpaid—yet also tragic and pitiful—figures can make it across the wobbly bridge to adulthood without falling in the choppy waters below. This is a kinky national ritual, our current form of pop-culture sadism. You can call it whatever you want—the collective ethos of a nation of Puritans trying to assuage sexual anxiety; a secular society combating a fear of death by torturing a cast of teenage voodoo dolls; or, at the least, a coded language communicating parental discomfort with our own children’s growing up—but you can’t deny that it’s a totally bizarre obsession, one that could happen only in the youth-obsessed, fame-hungry, prudish and pornish land of America.

Some kids get across—pop stars, for the most part. (Actors, like Amanda Bynes, Lindsay Lohan, Shia LaBeouf, and Zac Efron, who recently got into a fight on L.A.’s Skid Row with several homeless men, fare poorly.) Just a few years ago, Miley Cyrus wore a purity ring. She was worth billions of dollars to Disney, a check in the form of four seasons of Hannah Montana, 10 million albums, $225 million worth of movie tickets, a best-selling memoir, and 10 million Hannah Montana books. Now she’s put on her own costume—the butch femme, the funky porn star, the whitest girl alive to lay claim to southern “bounce” culture—topping twerking by puffing on joints; hot-dog-riding; front-wedgie-creating; faux-Clinton-and–Abe Lincoln–fellating; and grinding Madonna and kissing Katy Perry, though that’s probably best understood as the latter two stars’ sucking her youthful blood.

In the pop business today, these transfusions are more valuable than ever, as the music pitched to young and old fuses. Big pop stars like Perry are as popular with 8-year-olds and 18-year-olds as they are with 38-year-olds, everyone singing along to the double entendres (“melt your Popsicle,” “want to see your peacock-cock-cock”). The soundtrack to the kids’ movie Frozen is so far the No. 1 album of 2014. Pharrell Williams’s “Happy,” popularized by the movie Despicable Me 2, will likely be the top single of 2014. “Problem,” a peppy single from Ariana Grande, a 21-year-old star coming off a Nickelodeon show, is looking like the song of the summer.

In fact, if you run your finger down a list of today’s biggest pop stars, you’ll notice something curious: No matter what age they are now, most of them were teen stars, or at least made money off music, by 16 (other than country and hip-hop stars—though rappers enter the game early, it takes some time to monetize the flow). I present not only Britney Spears, Justin Timberlake, and Christina Aguilera, but also Beyoncé, on Star Search at 12; Katy Perry, recording on a Christian label under “Katy Hudson,” her real name at 16, the same age Pink was when she inked her deal; Drake, starring in Degrassi: The Next Generation; and Chris Brown, discovered at his dad’s gas station at 13. Shakira, Usher, and Taylor Swift had record deals by ninth grade. Rihanna left her crack-addicted father on Barbados around 15 for a deal at Def Jam. And the opposite end of the pop spectrum is held down right now by Lorde, an actual teenager.

When Bieber appeared on the scene in 2010, there was a different pop landscape, one in which teenagers still listened to teenage music. Over the prior decade and a half, teen-pop music had become ever more of a marketplace, as corporations began to wake up to the desire of dual-income families, parents racked with guilt over working long hours outside the home, for products pitched to 9-to-12-year-olds, or tweens (by the way, that appellation is rarely used in marketing, as the youth demo expands to include kids from 4 to 15). “Back then, it was unusual for a kid to have a huge impact on the music business, and within a few years it became a very usual thing,” says Steve Greenberg, the former head of Columbia Records who discovered Hanson and the Jonas Brothers.

Though Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, and Timberlake, who followed Hanson in the teen-pop explosion of the late 1990s, are often thought of as Disney stars, they were only booked on the new Mickey Mouse show as adolescents, and Disney had no claims on their later careers. Disney’s “Camelot era,” as the company calls it, was Hilary Duff as Lizzie McGuire (2001); Raven-Symoné (2003); High School Musical (2006); Miley Cyrus as Hannah Montana (2006); Selena Gomez (2007); the Jonas Brothers (2008); and Demi Lovato (2008)—all of whom benefited from Disney’s trademark corporate synergies, with TV shows, recording contracts, concert tours, Radio Disney spins, and Disney soundtracks.

But after years of Disney’s stars flashing purity rings and then silently checking into rehab, the stench of inauthenticity became too strong for many audiences—the company hadn’t produced a major teen star since Lovato. In their place came Bieber, emerging a little later than Taylor Swift. Though Swift is a genius songwriter, and Bieber mostly does not write his own hits, they were similarly positioned as naturals. Their backgrounds were divergent, though. In one study of adult adjustment in famous young performers, a majority suffered emotionally and from drug or alcohol dependency if two conditions existed: the child was poorly attached to his parents and the mom acted as manager.

Bieber did not come from the same type of home as Swift, whose parents have worked in finance and whose image, of a sensitive, sheltered girl consumed with issues of love and perfection, was close to reality. His childhood, in a small town in Canada, was gory. Both of his parents drank heavily, were about 18 and unmarried when they had him, and split up shortly thereafter. In fact, Bieber was a kind of Immaculate Conception, conceived while Pattie was on birth-control pills. His father, Jeremy, a muay-Thai fighter, was minimally involved in his life, and bills were hard to pay for Pattie, a part-time big-box-store clerk who cleaned herself up only after a suicide attempt, a stay in a sanitarium, and finding God. Bieber, like a boy version of Little Orphan Annie, performed on street corners collecting change.

But after Pattie (not a “momager” per se, but interested in a professional life for her son) uploaded some of Bieber’s performances to YouTube, an invisible hand came down. Braun, hypercompetitive, from Greenwich, Connecticut, and a nascent record man, then in his mid-20s, was looking for raw child stars. Leaving Dad behind in Canada, Justin and his mom moved to Atlanta to be near Braun, who paid not only for their relocation, but for every stick of furniture in the townhouse he rented for them, and the sustenance they put into their mouths.

Since he hadn’t been plucked by Disney, Bieber didn’t have to internalize moral rules. He could just be himself, whoever that was. “The label asked to do media training for Justin,” Braun told me, “and Justin said, ‘I don’t want to do that, to give scripted answers. That’s not me.’ ” And yet the Bieber persona was crafted. He hated elevators, liked heated car seats, and for romantic dates preferred hot-air-balloon rides. He was scared of spiders but liked turkey sandwiches. “I like brunette girls,” he once said, “but also like blonde girls. I like all girls!” He also has said, “It’s okay for my Beliebers to have a boyfriend, but please don’t kiss them in front of me, because I get jealous.”

On the topics of sex and religion, important decisions had to be made. Bieber didn’t have to pretend to be an eternal virgin, like Cyrus or Spears, and his early songs had lyrics about first dances that he knew had to be loving and slow. Though Pattie raised him very religious, he didn’t talk about Christ at his concerts, because, as Pattie told me, “the word Jesus is powerful. Demons are raised in the name of Jesus, people are healed in the name of Jesus.” Bieber added, “If you hear me speak of God in my concerts, I will say, ‘Thank you, God.’ You will never hear, ‘I want to thank Jesus.’ ”

Still, Bieber’s head could get heavy from wearing the crown. Once, after an Orlando show, he started crying. “Justin sat down and told me he didn’t like being famous,” Braun said. He told Bieber, “We can do the teenage-pop-star thing with no long-term career plan, and we can ride this thing for a few years, and your career will be done—and I mean over—or we can stick to our current plan, which is following in the creative footsteps of Michael Jackson.” But if you want the Michael Jackson career, Braun continued, “you have to grasp that you’re never going to be normal again.”

Bieber soon nodded in agreement. “I can’t have normalcy in my life, but I don’t have to get crazy about it,” he said.

Then Bieber turned 18.

Pattie told me her deal with Bieber was that, when he turned 18, there’d be no more school, no more rules, no more Mom with him on tour. “I hope I’ve instilled enough values in Justin that he makes the right choices,” she said. “Everyone goes through experimentation, whether in partying or another aspect of their life. They want to experience their own independence. And for Britney and some of the others, having to make those mistakes judged by the entire world [is hard] … I don’t believe Justin will go down that road. And if he does, I think it would be short-lived.”

But independence is hard when the eyes of the world are upon you, and Bieber’s early dislike of the media had grown roots. In 2011, he was deeply upset, says a source, when a woman in San Diego accused him of fathering her child, and he voluntarily took a DNA test to prove he was not the baby’s father. “The public wanted to hear from Justin, that he was okay while this was going on, and that made Justin feel strong,” says the source. “But it also made him feel people will say or do anything to [attack] him. And there was a residual impact.” To get as far away from Hollywood while remaining in Los Angeles, Bieber bought a compound in the remote suburb of Calabasas, where paparazzi are largely absent. Most of these communities, with sprawling Spanish-style homes, are gated with heavy security, which makes them popular with mainstream stars.

Unlike Jackson, who believed a true artist had to maintain a link to childlike innocence, training himself to speak in a high register after puberty (among other immaturities and predations), Bieber liked his maturing, deep voice, and the way rough, crass language sounded coming out of his mouth. Now that he was a man, he was less into Braun’s overprotective band of brothers and more into his homies, like Lil Twist, his best friend from years ago in Atlanta (when I met Bieber, Twist was at the mall buying him his first toiletry kit, something Bieber regarded as a masculine rite of passage). Smoking pot and inking tattoos like most of us order coffee (about 40 at last count), Bieber became a gangster, a godfather, only leaving home with his bodyguards as protection, and that protection could get rowdy. “It became like a scene from Caligula at Bieber’s house in Calabasas,” says someone who had been there.

This new persona, while perfectly in tune with the gritty, “ratchet” strain in hip-hop and R&B, was not a good combination with Bieber’s professional duties—no, no, not at all. The dead, dead doggy of the music business has one last bit of life left in it, and that’s around big blockbuster stars like Bieber. Winners take all in music today. With the top ten of top-40 songs played twice as much on radio channels as they were a decade ago, and the top one percent of artists receiving over 75 percent of CD and music-subscription-service revenue, celebrity artists have never been more valuable, which means Braun has plenty to protect. Braun, who has been raising money for a $120 million firm with other Über-managers, is a controversial figure in the industry, and several sources try convincing me his team isn’t as good as it thinks it is, though his artist list is impressive—Korean sensation Psy, Carly “Call Me Maybe” Jepsen, and, this year, Grande.

Braun has FAMILY tattooed on his wrist, and that’s what he was to Bieber: a father, a big brother, at least a “good uncle,” as a friend puts it. And he had given Bieber everything—the kid was selling hundreds of millions of bucks worth of his perfumes, plus he had a line of homewares and acne medication, and sold-out tours, CD sales, whatever he wanted. But Bieber didn’t seem to care. Like any adolescent, he was shedding his parental figures. Didn’t Braun say that the dream was Michael Jackson? He wanted that. He wanted respect. You didn’t have to listen hard to hear it. At the Billboard Music Awards last year, he strutted onstage in an outfit worthy of the hardest Detroit pimp (the color was black for the leather T-shirt, MC Hammer–type leather pants, and sunglasses, which he did not remove).

“I’m 19 years old—I think I’m doing a pretty good job,” he said as the audience erupted in some hoots and boos. “This is not a gimmick,” he spat out. “I’m not—I’m not—this is not a gimmick. I’m an artist, and I should be taken seriously. And all this other bull should not be spoken of.” He thanked Braun and his parents, then said, “I want to thank Jesus Christ,” whipping off the sunglasses and pointing heavenward.

Bieber’s career had started with his charisma, his magnetism, his talent, but now when he was onstage, he perhaps found himself lip-syncing, essentially miming, something like a hologram, with the goal of a Pepsi contract, living a life that had less to do with his real self than the ad department of a multinational corporation or the directives of a Live Nation executive. He was supposed to be an idol, a mini-Krishna sitting in a Ferrari instead of holding a flute, living a life envied by everyone in the world. And yet now he felt he had less free will than all those people who were supposed to be his followers. It was unfair, and now a second sensation, of adolescent self-doubt, was creeping in—that his real self might be disappointing for people if they saw it, and unloved, and might need the elaborate architecture that Braun had created to be interesting. “The kid developed real intense anxiety problems,” says a source close to Bieber.

About a year ago, a fissure opened between Braun and Bieber. “It was a roller coaster between ‘Justin is okay, everything’s going to be fine’ ” and ‘He’s not okay, and he’s not picking up the phone,’ ” said a source. He turned from his adopted father and Pattie and toward his biological father, who was much more visible in his kid’s life now that it included multicolored Ferraris. Record men based in the South with something to gain from an association with a pop prince also took a role in his life: Birdman, a head of Cash Money Records, who presented his new young friend with a loaner red Bugatti as a present, and Birdman’s protégé Lil Wayne, the founder of Young Money Entertainment. Ensconced in his new inner circle, Bieber wasn’t looking for complicated conversations—otherwise he might have to have thoughts about himself, and No, thank you, why do you think I get high and party with my dad?

When he wasn’t feeling numb, Bieber began to feel that the world was one of yin and yang, sin and deliverance, the good and “the enemy,” as his dad perhaps called the media—and maybe even Braun, whose relationship with Lil Twist became strained after Twist and Bieber made news for crazy driving in a white Ferrari and chrome Fisker Karma. (Twist, at one point, later blasted Braun for “put[ting] out false information to help their side stay squeaky clean … Fuck u Scooter and everything u stand for.”) Lil Wayne later threatened Braun directly, telling him Twist and Bieber were both under his care as little brothers and that “anything you got to say, when you see me, say it to my motherfucking face. And if you do happen to say it to my motherfucking face, I ain’t gonna make you eat them words, nigga—I’mma put them bitches on your tombstone.” So, for Braun, that was a little scary.

Bieber had invested his money mostly with Braun, but late last year, he struck out on his own for the first time with John Shahidi, a Californian who made his fortune with mobile games. “Justin was at a Kings game with a friend of mine, and he said he wanted to invest in a gaming company,” Shahidi said to me over coffee in Soho recently. “I said, ‘We can take your millions of followers, make a game, and make a lot of money. Or we can make the world a better place. We can help kids committing suicide because of negative comments online.’ And Justin said, ‘Let’s do it.’ ” The duo started Shots, a “positive” selfies app that doesn’t allow a follower count or extensive captions alongside its photos, thereby sidestepping the issue of hurtful comments.

Though Shots has gathered more than a million members, 80 percent of whom are women under the age of 24, the press has published some negative articles. “I was in Australia with Justin when the stories came out, and I got pretty upset,” said Shahidi. “I’m a 34-year-old, 250-pound man, and I teared up in Justin’s hotel room. And Justin said, ‘I started doing this when I was 13. I’ve been reading that kind of stuff since then.’ ” He continued, “Justin stands above the talk about him in public, which makes kids love him even more. He’s the child from a broken home who broke free. A symbol of hope.”

More than drugs, it’s love, the halo of awe, to which Bieber may truly be addicted, the very thing that made him uncomfortable as a kid (the wailing, the garment rending, the marriage proposals), but which was also, paradoxically, a kind of nurture. Though he can be bratty and mean to others, in the selfies that Bieber posts at night, he tempts fans, positioning himself in front of the camera, a baseball cap perched idiotically high on his head, eyelids drooping slightly in suffering, or at least existential confusion. On Twitter, he writes, “They can’t break us. They can’t get us down. We are too strong. We love too much. #mybeliebers.”

And his nadir in January of this year: Bieber was arrested in Miami for a DUI while allegedly drag racing in a yellow Lamborghini. When he was sprung, he hopped on top of the car that came to pick him up and, in case anyone missed the symbolism, posted a split-screen photo of him on one side and the famous courthouse pic of Michael Jackson on a car on the other. This composition had nothing to do with pedophilia or dying of a drug overdose, but was meant to emphasize their mutual victimhood. (Bieber had been driving under the speed limit.) He had sacrificed his childhood to be a vehicle for our nostalgia, and was no longer sure the Lamborghinis were a fair price.

The gangster clothes and tattoos don’t make Bieber look more like a man—it feels more like dress-up, a pirate costume. If he could remain a child forever, like Jackson, then that would be fine, or if he could stop pretending to be mature, then that would work, too. But staying somewhere in the middle is inherently problematic, and he’s going to need to transcend it very, very soon, unless he wants to nod out into the great beyond like Jackson, who, let’s remember, somehow went broke even though he had more of a fortune to spend as Bieber, or embalm himself in a multiyear residency for gawkers in Vegas, like Britney Spears. Postadolescence is fun while it lasts, but soon it’s going to come to an end. Does Bieber know this? Those around him say that he’s starting to get the message. This month, in fact, there was a moment of calm in Biebertown. After Miami, Bieber became religious, running around New York with the pastor of the Hillsong Church, looking for baptism, and, earlier, getting a tattoo of a cross on his chest and then the word forgive on his torso. “Forgiveness is powerful, forgive as Jesus died on the cross to forgive our sins,” he texted the tattoo artist later.

Bieber thought if he could be forgiven by Jesus Christ, then maybe the world could forgive him too. He forgave everyone, and that started to quiet his mind. He forgave Braun, who had put him on this unnatural path to stardom. He forgave his father for his inattention to him as a baby, and his mother for caring too much. He forgave CNN and TMZ, which had trespassed against him again and again. This month, when he was blackmailed over videotapes of him telling racist jokes at about 15, he went on bended knee to America at large, asking it to please understand that, back then, he was just a boy.

And what do you know? The forgiveness thing worked. Braun leapt to protect Bieber when the racist-joke scandal broke, and he was thankful. Boldface names in the black community, like Whoopi Goldberg and 50 Cent also forgave Bieber for the jokes, as did the Young Money executive, who added that Bieber “does not have a slave mentality.” The forgiveness was apparently contagious—Lil Wayne, perhaps with some prodding, announced that he had forgiven Braun, too.

Cool guys like Seth Rogen and Patrick Carney of the Black Keys, who have called Bieber a “moron” and a “piece of shit,” may never think Bieber’s a good dude after this year’s antics. But the music business will forgive Bieber if he has just one big song on his next album, and if he doesn’t do something insane like start rapping like Vanilla Ice. And with one confessional ABC interview, and one funny late-night interview, the media will forgive him. The past couple of years could be wiped away, with only the tattoos and the internet to remind him of the stupid stuff he used to do at an age when many young men tend to do stupid stuff. With Justin Bieber, we don’t know what’s going to happen. That’s why, despite our best convictions, we watch.

*This article appears in the June 30, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.