The 28-year-old Colombian-born artist Oscar Murillo has had a very good couple of years and has paid for it with a very bad couple of months. Until April, when he installed an elaborate chocolate factory inside one of blue-chip David Zwirner’s big-box spaces in Chelsea, he’d never had a solo show in New York. And yet astronomical sales of his scribbly, urgent, and defiantly un-precious paintings—which he makes using a broomstick and sometimes stitches together from multiple canvases, often feature “dirt” among their listed materials, and are tagged with large enigmatic words (YOGA, CHORIZO, MILK)—had made him perhaps the most talked-about young artist in the world.

Back in September, a Murillo that had been bought for $7,000 in 2011 was auctioned for $401,000 at Phillips; in February, a three-year-old painting, with BURRITO written on it, sold for $322,000 at Christie’s, and the prices of stacks of his other works had soared, too, appreciating by as much as 3,000 percent in just two years. It may seem crass to describe the arrival of a new painter by tracing the trajectory of his sales (not to mention none of that resale loot went to the artist but to those who had bought his work when it was cheap). And yet his story is impossible to tell otherwise; even the critical backlash is driven less by skepticism about his paintings (which many haven’t had the opportunity to see in person) than by a general anxiety about what fast money is doing to the art world and to those non-financiers who used to curate and adjudicate it. As the art adviser Allan Schwartzman predicted about Murillo earlier this year, “Almost any artist who gets that much attention so early on in his career is destined for failure.”

When I meet him just before the Zwirner opening, Murillo has a polite, boyish evasiveness, as if the rest of us, amusingly to him, aren’t quite as real as what is going on in the cartoon world inside his head. “I’d always thought that art was a no-go zone,” he says to me over lunch, across Tenth Avenue from the sprawling Zwirner complex, talking about his immigrant adolescence in London, where he considered becoming an animator before finding fine art. “And not because anybody prohibited me—my parents said, ‘Do whatever you want’—but because I thought, What do artists do? How do they make their money?”

Murillo works carefully over his words as he speaks them and often dresses like he’s hanging out in a skate shop, in T-shirts and saggy pants, maybe a backpack. Watching him set up the show at Zwirner, clambering on a cherry picker to adjust a projector like a kid climbing a tree, or adjusting the volume on the salsa he likes to keep going, you get the sense of how much of his life is a checklist of things to attend to, including talking to you. He’s energetic and bright-faced (the freckles help), sullen in flashes (his eyes slide off, disengaging), and, appealingly, just on the threshold of naïve. He has served so neatly as a screen for the projections of others’ ambitions and crusades that it’s not yet very clear how calculating he is and how much a genuine cipher.

Art collectors, who can get swept up in whatever is the thrillingly agreed-upon latest thing, have come to understand Murillo as a new Basquiat, however reductive that might seem. Until recently, he even shared a hairstyle with the late artist. (“Or at least the movie version of Basquiat,” notes Mera Rubell, one-half of the collector couple who are Murillo’s most energetic proselytizers.) Like Basquiat, Murillo is black, ambitious, and engaged with both art history and graffiti, and among the other things Murillo seems possibly to have cribbed from him is just how dangerous to be as an artist. It’s an especially complicated question now, given that the art market can function as the plutocracy’s method of prophylactic self-criticism. Murillo’s work is taken to attack privilege, and capitalism, and globalism, but is happily hung in the homes of those who make up the international art-shopping class and who seem to see in Murillo the flash of something new and great, yes, but, just as important, something intoxicatingly authentic, even a little bit hostile to them. And they are right: The amiable, ingratiating Murillo’s great artistic hope is to make the facts of his own biography an affront to the sensibilities of his collectors. His work is both aggressive and decorative, and his entire persona seems to hang in the balance.

And people like him, as I do. Two years ago this past spring, when Cecilia Alemani, who curates the High Line and the original art projects at New York’s Frieze art fair, met him, Murillo was a foreign-exchange student at Hunter College and was “working superfast” on an installation of paintings for a booth at the Independent Art Fair, she told me, sounding like a number of other acquaintances whom I spoke to about him: “His energy was great. He appeared rebellious but was incredibly kind and soft-spoken.”

But there is now shuffling concern that collectors are declaring him significant, possibly even writing him into art history, before the curators and critics who have always made it their job to decide get a chance. “It’s quite a new phenomenon for the market to have this kind of influence,” says Cesar Garcia, a Los Angeles curator who showed Murillo earlier this year at his space, the Mistake Room. Another was more pointed: “He went from an art fair to an auction house without basically having shows anywhere.” Murillo might have been the most pointed; he called his show at Garcia’s gallery “Oscar Murillo: Distribution Center.” In the last year, he’s had solo shows at a string of unimpeachable spaces—the South London Gallery, Isabella Bortolozzi in Berlin, Zwirner, Marian Goodman in Paris—and been promised a place in a painting survey at MoMA.

There used to be a certain backroom mystery as to what artworks exactly were for sale and to whom, but Murillo is young enough to have known only the new, more transparent click-to-buy era, when collectors sometimes shop by JPEG and art advisers plug things via Instagram, and both engage in the practice known as “flipping” (early buyers buy cheap, sometimes in bulk, reselling for a profit). The art-world hustle doesn’t seem to bother Murillo; being comfortable around money and money-talk is one sign of his “outsider”-ness. Some artists don’t like the shopping-cart vibe of art fairs, but Murillo is known for going. (There he was on my Instagram feed last month, caught by @theartreporter in front of a Gerhard Richter at Art Basel.) “Three years ago, he was at every fair, wandering around with his little backpack,” says a member of the traveling art tribe who admires Murillo’s pluck. “Telling collectors, ‘Hey, how are you, man? Come over, I’ll cook for you!’ All these rich white collectors were following him around: ‘Oscar! Oscar! Oscar!’ ”

One of those collectors who fell hard for him is the art adviser Stefan Simchowitz, who has bought 34 Murillo works for himself since 2011 (for as little as $1,500) and a similar number for clients (who include the actor Orlando Bloom and New York Giants owner Steve Tisch). He has become known as a sort of art-flipper bogeyman—despite never, he insists to me and on Facebook, having flipped a Murillo in his own collection (work he’s gotten for others, however …). He believes Murillo’s selling a painting to a wealthy collector is like a graffiti artist “tagging a home.” Rich people “are clueless and should be educated and not just be parasitic socialites. And I think that is what Oscar’s art does,” Simchowitz says. “In this expensive, fancy home arrives this ‘trophy’ that is actually more a Trojan horse.” Or, as Murillo put it in a recent edition of the very glossy L’Officiel Art (which features a photo of his uncle Carlos sunk in bubbles in the bathtub of a 1930s Beverly Hills villa, owned by a collector, that they were staying in during the Mistake Room show): “Any opportunity of artistic achievement comes with an opportunity to infiltrate a social class.”

Murillo was born, and spent the first ten years of his life, in La Paila, a small town in the Cauca Valley of Colombia, where sugarcane has been harvested since it was brought by the Spanish in the 16th century. Enslaved Africans were imported to work the plantations, and to this day their descendants, now a mix of hues, still live there, many employed in the confectionery industry. For almost a century, the local company Colombina has been owned by the Caicedo family, sugar barons whose complexion trends lighter than those of their workers and who control everything from the farms to the sprawling candy factory to the local fútbol leagues.

As a child, Murillo says, “I obviously knew who the owners were. But on my radar, they were so distant. They run the region.” That Murillo enlisted the company to help him stage his New York debut—Colombina’s dashing silver-haired executive César Caicedo did it for “the cachet,” Murillo thinks—is a delicious class-crashing achievement. “My grandfather passed away—if he was alive now, he’d be astonished,” Murillo says. “The closest he got to that family was in the ’60s; they did a lot of lobbying, so they would take the train from the village to Cali,” the regional capital, “and my grandfather would hand out Colombina chewing gum. To see this almost-equal-terms relationship, my grandfather wouldn’t believe.”

Murillo’s show at Zwirner, “A Mercantile Novel,” opened April 24 and came down in mid-June, eight weeks that enclosed a neat allegory about the art world’s limited patience for the undeferential. “Here’s a gallery which is, according to experts or whatever, one of the most successful in the world,” says Murillo, and it let him do something few others would have: not show any paintings. Instead, he set up a satellite single-machine Colombina chocolate factory. An assembly line of 13 workers produced about 5,000 Chocmelo candies a day—chocolate on the outside, white marshmallow within.

The factory conceit is not new in art; neither is even the idea of making chocolates in galleries (both Dieter Roth and Paul McCarthy had done so, and the art world ate it up.) But Murillo’s version was more evasive and personal, almost to the point of not being discernible. He had the workers video-record their time here, as if to say they were the ones watching New York, not the other way around. They were put up in Crown Heights, given English lessons two days a week, and ate every Friday with the largely female coterie of flawlessly cosmopolitan gallery employees. One of those staffers who spoke Spanish translated for me with a few of the chocolatiers while they hand-sealed custom-designed foil bags full of Chocmelos. None had ever been to the U.S. before; most had never left Colombia. They had first heard that Murillo had made it big as an artist when a Colombian newspaper reported Leonardo DiCaprio had bought one of his paintings. They were surprised that New Yorkers ate so much salad, and all planned to come back.

The Studio Museum in Harlem had originally invited Murillo to exhibit this spring. For a while, there was a plan to co-produce that show with Zwirner. But it turned out the gallery could accommodate the project better than the museum. Besides, Murillo says, “after kind of cementing the relationship, well, obviously Zwirner and I have to have sex in public together.” He then emphasizes that “A Mercantile Novel” was not just a gallery loss leader. “I mean, this is definitely not just being paid for by David Zwirner,” he says. “This is also me paying for it.”

But there was merchandise to move. Collectors could buy one of the gleaming crates stocked with one shift’s worth of the candies for $50,000. On one wall was a huge blown-up photo of his mother in her Colombina work uniform, head down, clearly exhausted from her labor. She lost that job in the mid-1990s, prompting the family move to London. On a stainless-steel Ikea shelf below the photo, Murillo had placed boxes of Jeff Koons–branded Dom Pérignon, each with a drawing of the Venus of Willendorf ancient fertility totem on copies of his mother’s employment file (“RETIRADA”). Interspersed were vases filled with melted chocolate and tennis balls on the shelf, which looked a bit like votive candles. The accumulated installation with its accumulated metaphors is called To the History of My Venus and was for sale. One afternoon when I stopped by the gallery, I saw the billionaire hedge-funder and collector Steve Cohen there, asking Murillo questions about it.

Murillo’s parents moved to London when he was 10 and knew no English. They are ambitious but not cultured people and worked as janitors; his father chose London, Murillo says over lunch, out of “naïveté”: “He was a huge fan of The Saint, this show with Roger Moore. It’s like the Bond movies: There is this assumption that London is the center of things, the birth of culture.” At first, he says, Murillo felt “an astonishing cultural displacement,” which turned him into what he calls an “amalgamation.” Which is to say, a highly adaptable and restless person, but one who defines himself as an outsider—someone who has a “hesitation to fit in.”

“At the time, London wasn’t what it is now,” he says, and even now, “it’s not the most interesting place to live—it’s kind of always, like, gray. But they managed to create this structure that is attractive to the world, and so they have wealthy people coming in and they inject money, and so the whole thing can function.” Murillo was a jock—he played on the junior Arsenal soccer team—and good at drawing. But when I asked him how his artistic talent was first recognized and encouraged, he said, “There wasn’t a recognition at first.” When he went to art school at University of Westminster to study animation, “I thought, If all else fails there is a kind of structure. But I only lasted two weeks. It was stop-motion, so to get a minute of animation, you have to draw for two months. And that was not much like me. So I went to speak to the fine-art people, and they liked my portfolio and took me in.”

After graduating in 2007, he worked as a teacher in a secondary school. “But I found it incredibly depressing,” he says. “It was bureaucratic, and I was kind of just telling kids to behave. I wasn’t actually teaching them anything. And I would work on my stuff in the evenings. And I thought: I have to stop this.” He quit his job and traveled to South America with his wife, Angelica Fernandes, whose family is from Venezuela and whom Murillo had been dating since he was 16 and she 15. “She doesn’t have nothing to do with the art world, but the sheer kind of loyalty—it’s amazing,” he says.

In 2009, “I find out she’s pregnant, and I think, Oh, fuck, if I’m going to take serious this art thing, I have to rethink my whole structure of survival.” For the next few years, during which he got his master’s at the Royal College of Art, he worked cleaning toilets at London’s so-called Gherkin building. He had the 28th floor, with its incredible views across the city, all to himself. “I worked from four o’clock in the morning till eight, and by nine o’clock I would be in the studio—until nine o’clock in the evening.” His wife got a degree in teaching but “kind of took the back seat and took care of the baby,” he says.

Over the next couple of years, he staged a series of memorably class-conscious shows in London: “The Cleaners’ Late Summer Party With Comme des Garçons,” at the Serpentine, in which fellow janitors danced with the art world; a show turning a gallery into a yoga studio; an installation at the South London Gallery “with canvasses on the floor, very much works in progress, sculptures for corn and grinders for corn,” as the curator Margot Heller puts it, raising the question “What is waste and what is commodity?” The show also included a lottery with £2,500 tickets whose second prize was a trip to Mexico not for the ticket holder but for a friend of Murillo’s from La Paila. First prize was a collection of mementos from a trip Murillo had taken back to Colombia. David Zwirner found himself with the winning ticket.

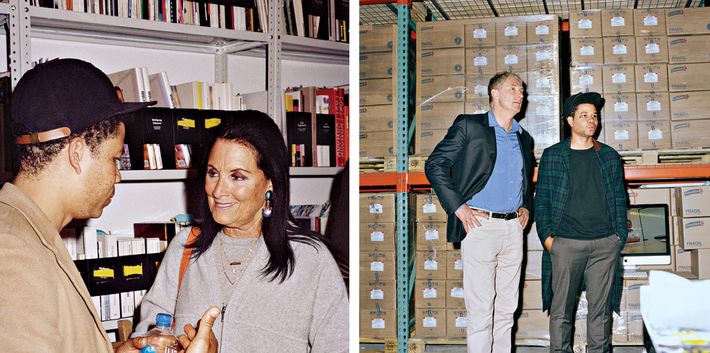

Murillo’s true ascent began only when he met the Rubells. They had begun collecting as newlyweds in New York in the mid-1960s, setting aside $25 a week to collect art—they were early believers in Basquiat, Richard Prince, Mike Kelley, and Keith Haring—and discovered Murillo two years ago at the Independent Art Fair, where he was showing with a London gallery, Stuart Shave.

“I think in general a lot of good artists have a rush at one time or another,” says Donald Rubell, fresh from his morning tennis game, when we meet up at the gallery a couple of weeks after the raucous opening of “A Mercantile Novel.” It had spilled out onto the street, with blaring salsa and food trucks, but the Rubells, who are now based in Miami, couldn’t make it up.

“You know, Schnabel had a rush in the ’80s,” says Mera Rubell, in a billowing pin-striped coat, a fedora over her spiky hair. “Haring had a rush. Basquiat had a rush.”

“Jasper Johns’s first show—they were $900, but they all sold out in minutes,” says Donald. “It doesn’t define a good or a bad artist. A lot of bad artists also have a rush.”

“But we become suspicious at that,” says Mera. “Because we think there’s some evil or manipulative force. You think that it’s premeditated. You think it’s like a kind of intentional commercial drive. But, just in our experience, it’s hard to create it.”

We are sitting next to the chocolate machine, while the workers are on break, and the Rubells are performing for my benefit a remarkably unguarded account of their relationship to Murillo and their feelings about his work. “We have not had a sit-down like this with David Zwirner about Oscar,” complains Mera. “And it bugs the shit out of me. You’d think he would call us up and say, ‘Who is Oscar?’ We know him so well.”

They hadn’t yet heard of him when they saw his work at the Independent in 2012, they tell me. “But all the paintings were already sold,” says Mera. They knew the gallerist. “Stuart said, ‘I wish I knew you were interested.’ We said, ‘How could we know we were interested?’ We’d never heard of this artist. We thought, We need to meet this young artist because—”

“It’s not just who he is; it’s who he can become,” says Donald.

Murillo had no work left at his Hunter studio. When Shave told him that the Rubells were visiting, he decided to spend the next two days on a painting bender.

“We arrive at Hunter at 9 a.m., and he has now painted for 48 straight hours. He hijacked this big space because everyone else had left for Easter holiday,” Mera says. He looked exhausted after the binge. “When we met him, we thought he was a homeless person,” says Mera.

“I immediately held on to my pockets and headed to the door,” says Donald.

But then they took a look at his work. “We couldn’t believe the energy,” says Donald.

“There’s one painting there, Milk, and I say to Oscar: ‘Have you ever made a painting this good?’ ” says Mera. “ ‘Because I can’t imagine anybody making a better painting than this one.’ ” The Rubells agreed to buy the whole batch. Then they did something they hadn’t before: offer to let him use one of the galleries in their foundation, a former DEA facility in Miami adjacent to their home, while they’d be away that summer.

“People are always trying to figure out what the power of the immigrant is,” says Mera.

“No, they’re not,” says Donald.

“Let me just finish my point. The power of the immigrant is that they always show up. You don’t always know if you can deliver, but you always show up. Oscar always shows up. We give him 24-hour access to the space, and every day we get these updates: Look at what he did last night, look at what he did this morning, look look look. He makes over 40 works in six weeks … and he was cooking sausages for the staff”—Mr. Paisa brand.

When they returned, they said they wanted to buy it all and put on a show at their foundation. But there was some disagreement: Murillo sought to exhibit everything that went into the process of making the work (including the sewing machine). But they knew better. “We said, ‘The world does not know you, Oscar,’ ” Donald remembers. “ ‘The first go-around, the world should know the best that you can do. As elegant a setting as you can.’ ”

“If he had his choice, he would have left the paintings on the ground,” says Mera. “He’s not comfortable being so historical. He’s a little embarrassed to be monumental. He’s a little bit intimidated by what he’s created. But when the frames arrived and he put the paintings up on them, it was like a moment of silence.”

“Oh my God,” recalls Donald.

“We end up showing just five paintings,” Mera says. The show opened during Art Basel Miami in December 2012. And that was the beginning of Oscar Murillo, art star.

But the Rubells weren’t finished with him. “It happens we’re friends with some Colombians in Miami,” says Mera. “We tell them we met this Colombian artist who now lives in London, who’s from this small town where his family cuts sugarcane with machetes. And not only do they know the town, but this person that we know—his uncle owns the factory.”

“They’re our best friends in Miami,” says Donald. They set up a meeting in their living room between César Caicedo and Murillo. “And it was fascinating … And the first thing they said was, ‘Oscar doesn’t have an upper-class accent.’ ” Upon meeting, Caicedo and Murillo “both assumed the traditional roles that they had in this town. There was a lot of tension.”

“Not tension,” says Mera. “He was returning to the core of his identity. Of this town, this family, working in this place. It comes back to, you don’t bring your history of poverty and lower-class family when you’re being wined and dined by money and power,” she says. “You just don’t! Look, I’m an immigrant. My earliest memory is of a displacement camp in Germany. For me, this fantasy of going back to a place where you can show how far and how lucky and how fortunate … In that living room, talking to César, you could feel Oscar saying to himself, ‘But for the grace of God, I am here.’ ”

“That sounds like a B-movie.”

“Some artists have compelling stories,” counters Mera. “And Oscar, from when we first met him, there was this feeling that, They want to know me for my story, and then they want to crucify me for my story. It’s too good a story.”

“He didn’t have any paranoia about people crucifying him for his story.”

“No, I think he was conscious of it.”

“We in the art world were conscious of it.”

“I mean, he cut his hair. He’s trying to be himself. I mean, people are comparing him to Dieter Roth. He’s Paul McCarthy,” Mera says. “They think that this is some kind of gimmick. And I understand why they would think it is some kind of gimmick.”

“Oscar is a very, very intuitive person,” says Donald. “He understands it’s important for him to somehow maintain …”

“The core of his identity,” says Mera. “It’s almost like he needs to remember. As an immigrant kid, my parents embarrassed the hell out of me for so many years. You don’t know how embarrassing it is when your parents don’t speak the language. They don’t dress right. But Oscar from the very beginning wasn’t embarrassed to bring his parents into his universe.”

“This is something we disagree about,” says Donald, by which he means the biographical aspect of the painting-free Zwirner show. “To me, Oscar is blessed. He’s an artist. And yes, this is very important to him,” he says, waving his hand at the factory. “But he’s really a great painter. Well, no young artist can be a great painter. He’s a very good painter. He has enormous promise. This,” he continues, waving his hand again, “is something else. But Mera thinks this is the essence—”

“Donald, you’re stuck on him as a painter.”

“I don’t reject this per se,” says Donald. “But there is no way the story of the artist is the essence of an artist. The essence of the artist is what he can do with the story.” He adds: “It’s a rare thing when you see someone with so much raw talent. All the cynics on Oscar are not relating to work they’ve seen. It’s work they haven’t seen. With Oscar, once you see the work—no one stands in front of his work and says, ‘Not interesting work.’ You could argue things like the market is too high, it’s too fast, but the money is irrelevant. Whether it costs a lot or costs a little, either the art is good or it isn’t.”

“The artist becomes victimized because the auction market goes where it goes,” says Mera. “What is dangerous for Oscar is that with all these accusations—he’s copying this one, he’s copying that one—is that he has to be careful that he doesn’t give up territories which are uniquely his. No one paints with a broomstick. His technique is so unique to him. His signature is literally a handprint. When I see those strokes, I think it’s a subliminal memory of his grandfather machete-ing his sugarcane.”

Or perhaps, Donald suggests, it’s just that he worked with a broom as a cleaner.

“I think we have memories we don’t even know,” says Mera.

It was early in the afternoon on June 14, the last day of Murillo’s show, and he was back in town after the “more civilized” Marian Goodman opening in Paris, making more of those vases filled with melted chocolate and tennis balls. Salsa music was blaring.

The coverage of “A Mercantile Novel” had been brutal, even mocking. At the press preview, Murillo had seemed defensive. “It isn’t about bringing people from a foreign country and getting them to do work,” he tried to tell reporters, stumbling to explain his use of the word novel. But the preview was thronged by both enthusiasts and doubters. Bloomberg’s reporter opened her dispatch: “ ‘I am not a star,’ artist Oscar Murillo said as he signed autographs.”

“For his first solo show in New York, the hot young painter Oscar Murillo has blinked,” wrote the Times in a not atypical assessment, going on to call the show “obvious,” “laborious,” “macho,” and “self-flattering.” The Art Newspaper ran a story about the reaction, succinctly headlined: “Haters gonna hate.” The show didn’t give many people what they wanted, a look at the paintings, and instead gave them something that was difficult to engage with. Later, at Frieze, when I was introduced to Laura Hoptman, who is curating the upcoming MoMA show, and the museum trustee A. C. Hudgins, who is a big supporter of Murillo’s, neither was in a mood to talk.

Zwirner blamed it on “a pattern in the local press where they’re very hard on young artists who don’t live here, who come from other places.” One Zwirner-ite thought there had been a whisper campaign by Gavin Brown, who represents an artist, Joe Bradley, whose paintings look a bit like Murillo’s.

When we had lunch, Murillo referred to himself as “a young emerging artist,” as if that in itself might tamp down expectations. “I guess in my head I know what I’m doing,” he told me later at the gallery, clutching two iPhones as we discussed his critics and their misunderstandings. “You know, I think the problem is the need for information, immediacy, means that people don’t look. People don’t look or people don’t see.”

At the gallery for that last day, I poked my head through the plastic flaps that obscured the assembly line from the public area. The workers and Murillo were celebrating: They’d been watching the World Cup, and Colombia had soundly beaten Greece 3-0. Murillo was polite, as always, but he told me that he was done talking. All of this had been enough.

*This article appears in the June 30, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.