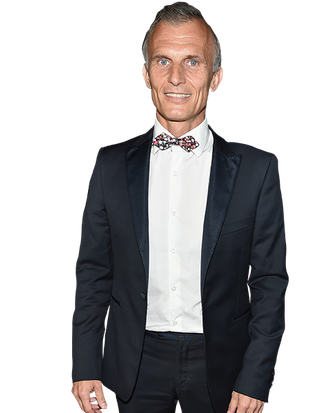

Once Richard Sammel completes his role as Nazi turned vampire Thomas Eichhorst on The Strain, he’d like to display his lighter side on a series like Suits. Seriously. Talking on the phone from his home in Paris, the 53-year-old German-born silver fox makes a point to highlight more comedic work he’s done on stage and screen. And in conversation, he’s markedly looser and more cerebral than his tightly wound, ultimately corrupted Strain alter ego. [Note: Spoilers up through last night’s episode of The Strain from here on out.]

But after last night’s episode, in which we witness the turning point of Eichhorst’s origin story (and finally see the Master’s ugly punim) via his willing transformation into strigoi, we were primarily compelled to inquire about TV’s most reviled undead SS serviceman. Sammel, a prodigious talker, also expressed his awe at massive co-star Robert Maillet (who, while unsung, gives the Master his physical form), while discussing his due diligence as a German actor crossing the border and how The Strain is basically “Star Wars on the ground.”

It’s nice to speak with you outside of your menacing Strain persona.

Yeah, once in a while, I have to get out of there, get my life together again, you know?

Had you seen what the Master’s face looked like before last night’s episode aired?

I think it was actually the first or second day of my pilot shooting.

And what did you think?

I was quite irritated. It’s basically the fear of the unknown that triggers my whole curiosity about the thing, and then I had read the books. And being confronted so early with a fixed and definitive image of the Master was kind of disturbing, because I was not yet prepared to see the full, propped-up Master in front of me. I would have liked to go on for some weeks or months for the Master to build up in my mind, but here it was, and it was Guillermo del Toro’s interpretation, and that was what calmed me down and convinced me. The creation of this vampire world is so dedicated, so committing and so passionately in love with these creatures that you get the idea that they actually exist. So it was thrilling, but you know, Robert Maillet is already very impressing when he has no makeup. [Laughs.]

We also see the culmination of Eichhorst and Abraham’s encounters in the concentration camp. Is it a thin line between making Eichhorst a human being and sentimentalizing him and that relationship?

You know, we had the vampire [Eichhorst], which is very clear, because he’s aesthetic and very enigmatic and a very powerful person. And then I had the chance to play the human being he was before. And as he is a Nazi, the result is very clear: He’s a very, very, very bad guy. So in order to distinguish him from this arc he would go to, this enabled me to do the human bad guy as human as possible. My duty as an actor is to bring as much life and surprise to a character as possible. So we try things out, and of course, when you risk something like the humanizing process of Eichhorst as a Nazi, it’s a thin line. But I’m not alone to decide it. It’s Carlton Cuse, it’s the other writers; there was a wonderful director. We spoke a lot about this, and we thought we could do this, because it’s more disturbing than if he’s in the line of what we wait for him to do.

And it seems like Eichhorst is motivated by an envious curiosity toward Abraham’s humanity.

Oh yeah. I mean, he’s jealous of this humanity he sees in young Abraham, and at the same time, I think he tries to transform this jealousy into friendship. So he rises to the humanity of Abraham, but he sells it as if he goes down to him to treat him equal. It’s a weird thing, you know?

Would you say that cowardice is Eichhorst’s fatal flaw?

I don’t know if cowardice is the right term. I think more complete corruption by power, and narcissism, and hubris. From his point of view, what he does in the flashbacks is not cowardice at all. He gives himself completely up to a Master who might not fulfill his promise either. It’s a poker game. He believes in this vampire monster, and this vampire monster, when he finally meets him, he actually could just kill him. He’s not empowered by anything, but he gives himself completely in. He’s corrupt, humanly speaking, in the presence of other humans, particularly the Jews. But that’s the story of the Nazis anyhow.

Nazi and other villainous performances range from stark evil to complexly human to cartoonish evil. Is there one you look at and admire?

Oh, yes, of course, I’m thinking immediately of Laurence Olivier in Marathon Man. I’m thinking of Anthony Hopkins in Silence of the Lambs. I’m thinking of Christoph Waltz [in Inglorious Bastards]. All those characters, with the exception of Laurence Olivier, felt good doing what they did. They had an ironic smile, which then was seen like sarcasm. But Dr. Lecter enjoyed very much what he was doing, and so did [Waltz’s] Hans Landa. He loved the milk in the very first scene, and he loved to be considered not only the Jew Hunter, but thinks of himself in great ways. He’s able to find people others can’t, and then he exterminated them, and it’s joyful for him, because then he succeeded again. It’s like a broker who’s made a risky deal and brought $200 million home to his bank. He gets a bonus. Look at [Adolf] Eichmann. He was deciding about thousands of people by putting the number of a train which would go to Auschwitz or not, with no compassion whatsoever. They were just numbers, and it’s hard for us to understand this kind of functioning, yet we have to do it. This is why we do movies about it.

Now that you’ve made a splash with this role, what kind of non-Nazi-themed shows have you been enjoying that you’d like to be cast in?

I like very much The Newsroom. I like very much Suits. And then, of course, you have those who are already finished like Breaking Bad. I was a huge fan of Sopranos. But talking about the first two I mentioned, it’s not playing supernatural guys or extremely bad or crime stories, but kind of a normal, contemporary situation where you have to deal with concerns people normally have: money, news politics, how to balance it with your private life, a love story in between. And I’m very interested by comedy, I just say. [Laughs.] You won’t believe it, but that’s where I come from. And look what I’m doing now. It’s incredible.