Cliff Martinez is a synthesizer. For the composer of the minimalist score on The Knick, which ends its first season Friday night, instruments requiring wires and keystrokes are both a tool and a philosophy. Just as a synth can translate and distort a musical concept into an unrecognizable sound, so does Martinez to 100 years of film music. Directors come to him with “temp scores,” sourced cues from other movies that reflect the musical ideas they’re chasing, and he synthesizes them through his own set of plug-ins. “A lot of my interesting scores,” says Martinez of his process, “are the result of me trying to imitate someone else and failing to do so in an interesting way.”

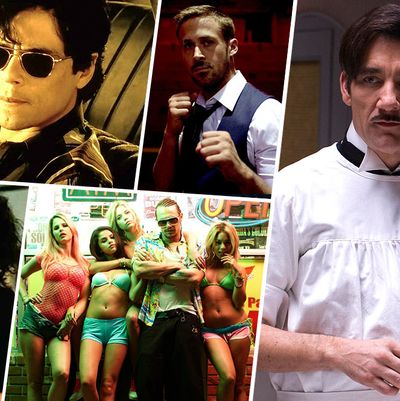

The Knick marks Martinez’s 35th score and 11th collaboration with director Steven Soderbergh. When they teamed up for 1989’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Soderbergh was a first-time director and Martinez the former drummer for the Red Hot Chili Peppers with a single composing credit to his name (an episode of Pee-Wee’s Playhouse). Since then, he’s worked across genres with directors including Nicolas Winding Refn and Harmony Korine. Martinez walked us through some of his more memorable scores.

The Knick (2014)

Laying electronic music over Soderbergh’s period medical drama never raised an eyebrow. There was no threshold to going too modern. In 1900, John Thackery (Clive Owen) and his staff were on the cusp of innovation, living the future. Soderbergh knew immediately what he wanted from Martinez, handing him a temp track comprised of cues from his own work on Spring Breakers, Contagion, and Only God Forgives. Martinez’s challenge was unearthing enough ideas to fill the ten hours of screentime. The composer says an average film takes him about five to 12 weeks to score. “The Knick was six months,” he estimates. “I got a running start and at a certain point, you begin putting out a one-hour episode a week. At that point, it became very daunting. Artistically, you have themes and variations in a feature film, maybe an average of 15 minutes of music. There was around three hours of music from The Knick.”

Martinez had only seen the show’s first three episodes when he began to write. He started where the audience did: the operating theater. “Steven indicated that he did not want music in the surgeries. I thought, I want to get in on that.” He wrote a piece of music for the show’s first surgery scene that was ultimately used for the opening scene, in which Thackery is seen injecting cocaine between his toes as he rides in a carriage from his opium den to the hospital. Another early piece stemmed from an episode-two scene where Edwards quarrels with Algernon (André Holland) over the aortic aneurysm.

What we hear is a vibrant mix of computer-created sounds and organic recordings, including electric guitar, Indian flutes, and the cristal baschet, Martinez’s instrumental soul-mate. “It’s played with wet fingers on glass rods. I’ve tried to wedge it into every film score I’ve done since the year 2002, but it seemed oddly appropriate and period-sounding. It sounds a little like a calliope if you play it [in a] staccato kind of way. There are a few. But other than that, there isn’t much that isn’t synthetic instruments. It gives it an otherworldly texture.”

Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989)

“Steven is characteristically hands-off. He gives you a specific overall design [and] points you in a narrow direction, but then he leaves you alone unless you get off track.” Except, Martinez says, on their first film. During post-production on Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Soderbergh would come over to his composer’s house, and together, they’d sit at the piano working out material. Martinez was okay with that.

“Up until then, my professional career involved hitting things with a stick to produce sound,” he says. “To be deprived of doing anything rhythmic at all, [to be] doing things that were all textural and ambient, was quite a shift.” Martinez recalls being very nervous about composing for the screen and felt consumed by technical issues, like syncing sound with videotape. Studying Brian Eno, Soderbergh’s inspiration for the soundtrack, helped him develop a texture we still hear in scores like The Knick. “I thought that Eno’s music defied analysis, and the fact that I couldn’t figure out how to closely imitate it was probably a good thing. I stumbled onto what has now become a lifelong formula for writing music: ‘Borrow’ what you can from other artists you admire, and fill in the rest with your own personality.”

King of the Hill (1993)

More sentimental and nostalgic than anything else in his filmography, Soderbergh’s Depression-era drama demanded Martinez’s jauntier side. Soderbergh was looking for something John Williams–like, which confused the composer. “I thought, Oh, gosh, why would he choose me to do that?”

The composer says Soderbergh never looks for anything “broadly emotional,” but King of the Hill needed cues that could delve underneath the point of view of a child. “I think because Jesse Bradford was such a Mona Lisa character, the music needed to fill in what you didn’t know about his emotions,” Martinez says. He knew emulating Williams was an impossible task. That’s the relief of building off inspiration. “I can’t think of how many scores where I’ve tried to sound like Brian Eno or John Williams or Thomas Newman and completely blown it, but came up with something interesting on its own.”

Schizopolis (1996)

For Soderbergh’s second film, Kafka, Martinez attempted to write an entire score of accordion music. “That was a disaster,” he admits. But cues from the rejected soundtrack made their way into the director’s experimental comedy, Schizopolis. “I gave Steven an hour of outtakes and things I had written that didn’t have to do with any film. He used them eclectically. Steven also wrote and performed some of the music in Schizopolis. So there’s absolutely zero continuity. It has an ‘anything goes’ feeling.”

Traffic (2000)

For Traffic, Martinez recruited guitarist David Torn because of his long career manipulating acoustic sounds. And Martinez was a fan, so why the hell not? Working from his home in Woodstock, New York, Torn would send “textures” that Martinez, in Los Angeles, would then manipulate into compositions. “David is not the kind of guy you would give a piece of sheet music and say, ‘Play this part.’ You call him up and say, ‘Give me the sound of giant blue babies levitating over the mountaintops.’ Or you speak in general terms about a mood … Our process was looser and more abstract.”

Narc (2002)

Don’t assume Martinez’s job involves hours and hours sitting at a computer. He’s also a handyman. Unable to find the right sound to underscore Joe Carnahan’s crime film, Martinez decided to build what he was looking for. “I rented a truck and went to a part of Los Angeles dedicated to scrap metal. I found some juicy pieces — the bigger, the better. And I made a big aluminum frame in my living room, where I removed all the furniture and hung all the scrap metal. It was there for about three months. It looked like an art installation. I played the thing with mallets.”

Solaris (2002)

Martinez first encountered the cristal baschet while scoring Soderbergh’s remake of Andrei Tarkovsky’s Russian science-fiction film. The composer thought the ethereal instrument would dominate the film’s palette. The less-glamorous steel drum filled that role. “Steel drums come in different flavors. In the country of origin, Trinidad, they call them orchestras. They have basses, baritones, altos, and sopranos. To us North Americans, the Jimmy Buffet sound is the soprano. I had the baritones for Solaris. To our ears, it doesn’t immediately evoke the calypso/Trinidad flavor. I didn’t know it would work, really.”

Solaris remains one of Martinez’s favorites of his own work because, in a rare instance, the music transformed the picture. “Sometimes the music gets a small role, sometimes a big role,” he says. “A lot of people wouldn’t notice the different between the two having not seen a movie without music. I just thought Solaris was transformed to a greater degree.”

Contagion (2011)

“Contagion went through a lot of changes and phases,” Martinez says. “Of all the movies I’ve worked on with Steven, it was the most revisited and re-edited.” Initially, Soderbergh wanted a sound akin to Ennio Morricone’s Battle of Algiers and defining films of the ‘70s like All the President’s Men and The French Connection. Then it needed to be more energetic, a Tangerine Dream, “retro synth” riff. Then he referred to contemporary composers. More active, more rhythmic. He’s a fan of the golden period of film in the ‘70s.

What they wound up with is one of Martinez’s biggest scores (and one of his rare studio pictures). “The orchestra seemed like a good idea for Contagion, to generate a sense of scale, [which] wasn’t in a lot of the scenes. It’s about a world epidemic, and it’s mostly people in a small room talking to each other. The orchestra was appropriate to generate a sense of size.”

Only God Forgives (2013)

According to Martinez, Soderbergh and Nicolas Winding Refn have similar musical tastes. They both prefer dark, ambient sounds — music that stays out of the way. The difference being that Winding Refn wants the music to play for extended periods of time. “Most people wouldn’t notice that, but it’s a big deal for me,” Martinez says. “There’s a piece in Drive that I think is nine minutes? It really gives a chance for the music to develop and tell a longer story.”

In Only God Forgives, Martinez goes to town, with musical influences ranging from classic Hollywood to religious dirges to Polynesian music. The film’s opening track incorporates Samoan drums (“they aren’t drums, really, they’re hollowed logs they hit with a stick.”). Later, the thai phkn, a three-string electrified lute, can be heard. It all blossoms into a Bernard Herrmann homage that Martinez recognizes as a transposition of its own. “In his case, it was Wagner for the romantic things he does in Vertigo. Nicolas had used The Day the Earth Stood Still, the original, in his temp score. There were a couple places in Only God Forgives where a romantic touch was required. I was trying to channel Herrmann channeling Wagner.”

Spring Breakers (2013)

Thanks to Harmony Korine’s Florida-set bacchanal, Martinez now shares album space alongside Skrillex with tracks like “Rise and Shine Little Bitch.” While his working relationship with the dubstep maestro was minimal, he did latch on to his music as a starting point. “’Bikinis and Big Booties, Y’all’ is actually a slowed-down version of ‘Scary Monsters and Nice Sprites,’ the Skrillex piece that opens the picture. I think I revisit that theme, the chord changes and the melody, about a half-dozen times in the film.”

His revised “Scary Monsters” tune turns full haze in the film’s final sequence, a slow-motion shootout at Gucci Mane’s mansion. Originally, Korine had settled on“Adagio for Strings” by Samuel Barber to provide an elegiac counterpoint to the action. Martinez protested. “Because it was the end of the film, that’s where the composer gets to do his final summation,” Martinez says. “I’ve run across this a couple of times: A director wants to throw a completely different piece of music that doesn’t fit in stylistically, but it happens to work for the ending. I always resist that. This is the place where all the themes you’ve developed over the course of the film come together. I wanted something we’ve heard in the film to be used in the end. So I combined Skrillex’s piece with this elegiac symphonic piece as temp music. That’s how the ‘Scary Monsters’ strings piece was born.”