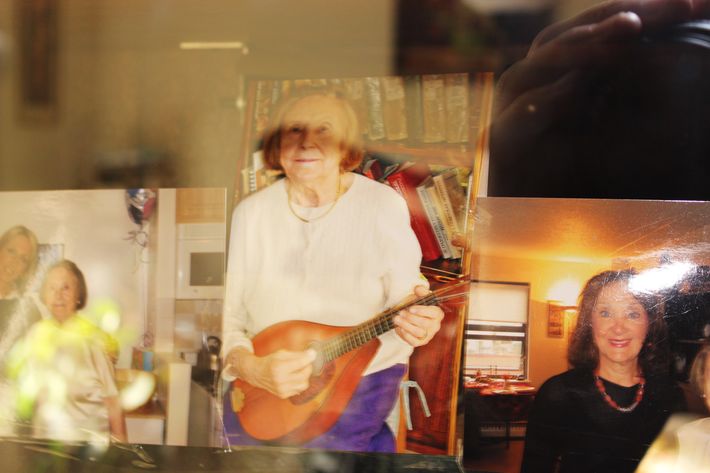

Emily Kessler, a 97-year-old Holocaust survivor from Ukraine, plays music for herself. From inside her apartment on the Upper West Side, she practices her mandolin and sings folk songs as a means to bring herself joy and remember a time before the war, when she was with her family.

“We were singing,” she says of her childhood. “My mother, my father. My mother had a voice that when someone heard [it], they thought the radio was playing.”

Kessler is her own humble talent, a soulful voice packed in her petite frame. When she plays for audiences, they’ve typically been adult groups at community centers. But on Monday night, Kessler is slated to make her debut at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall, giving a solo performance to coincide with a fund-raising dinner held by the Blue Card, a nonprofit that offers aid to Holocaust survivors. The performance is part of her incredible odyssey that started when she was a widowed teenager, running and hiding from the Nazis with a baby son and adopted daughter. Masha Pearl, executive director of Blue Card, says the group chose Kessler because her display of personal strength and commitment to music has been an inspiration for the group. “She’s able to channel something very painful and deep,” Pearl said.

When the Nazis invaded Ukraine in the summer of 1941, Kessler’s husband, a journalist, went to fight them and never came home. Before her family was rounded up and taken to concentration camps, Kessler says she watched the Nazis shoot her brother and later watched S.S. soldiers kill her mother and father. Widowed with a young child, Kessler survived the war through a combination of extraordinary grit, the kindness of strangers, fake documentation papers, and several years roaming between homes and sleeping in attics and parks to avoid the police or S.S. officers. Back then, she had blonde hair, the bluest eyes, a Ukrainian surname, and lied about her Jewish roots to survive.

“They ask me, ‘Are you Jewish? Are you Juden?’ I say I am not,” Kessler recalls of one of many encounters with Nazi soldiers. Many memories are so disturbing, she prefers to keep them to herself.

“I lost my mind,” she says. “I didn’t understand [anything]. My fear took away my mind. I wanted to go only home. Until now, I don’t how I survived with children, without food.”

Through fake papers, Kessler was able to avoid the camps. Eventually, she made her way with scores of other refugees to New York, where she has rediscovered the mandolin. She sings in Yiddish and Russian and plays scores of ballads and folk songs. Her typical audiences are small groups of seniors. Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall, home of the New York Philharmonic, has nearly 3,000 seats.

Kessler is not nervous. She has her outfit, a black blouse and skirt, prepared. She’s also packed wooden blocks she uses as foot rests and to support her mandolin on her lap. She has six songs prepared, and she’s been practicing, but she’s also brought lyrics to a few more of her favorites, just in case the crowd at Lincoln Center asks to hear more of her music.

“It makes you forget the bitterness of the life, the unfairness, and the cruelty of everything,” she says of music. “Music is not cruel. It’s always peace and love.”