During the 1920s, as a large part of America danced to the sounds of the Jazz Age, the poet Carl Sandburg took it upon himself to cross the country and collect indigenous folk songs, encompassing everything from backwoods reels to black spirituals to Mexican ballads. He understood that there was something uniquely American imbedded — and, portentously, brewing — in the music. A friend gave me the book, The American Songbag, 20 or 25 years ago. The dedication Sandburg writes at the front of his book has stayed with me in the years since. It appears as prose, but I’m going to spread it out so it reads like the poetry it is:

To those unknown singers

who made songs

out of love, fun, grief

and those many other singers

who kept those things of the heart and mind

out of love, fun, grief.

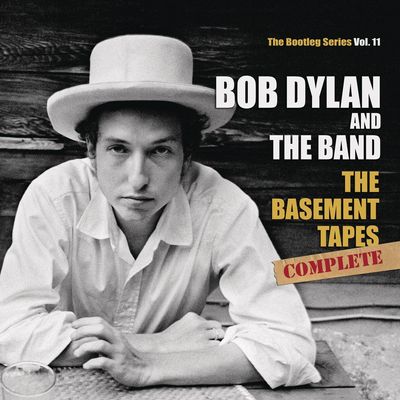

The words came to mind again as I listened to the new and allegedly complete release, out this week, of Bob Dylan’s fabled Basement Tapes. With this six-CD collection, their lingering mystery — the fabled sessions the singer did with the Band in various home studios in Upstate New York, way back in 1967 — is finally revealed for any and all. Some of the songs from these sessions came out in unauthorized fashion, in the 1970s; dubbed, at first, Great White Wonder but released under many different names, it was said to be the first bootleg, and ultimately, the best-selling one of all time. (There’s no way to know for sure, of course.) Half a decade went by — an eternity in pop years — before the singer and his record company agreed on an authorized release. This set, dubbed The Basement Tapes and encompassing two LPs, came out the same year as Blood on the Tracks, to universal raves. (Robert Christgau, in The Village Voice, said it was the best record of 1967 and 1975.) And yet neither were really “The Basement Tapes”; both collections included songs with a different provenance, and the latter even featured overdubs. And it was always known that that more tracks remained. Todd Haynes’s cinematic meditation on Dylan, I’m Not There, was named after an unreleased Basement Tapes track, and Sonic Youth’s moody cover of it marked the soundtrack. Out this week is The Bootleg Series Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete, credited to Bob Dylan and the Band, and supposedly encompassing all of the sessions’ extant songs, with a few additional takes of key numbers thrown in.

You’ll note that this is called Vol. 11. Dylan’s official “Bootleg” series began in 1991 with a three-CD set called Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased); to this day, it remains a mind-blowing assemblage. Here was a guy with 30 albums to his credit being able to proffer nearly 60 tracks of largely unheard archival material, virtually all of which were highly engrossing, and some large part were as good as anything the singer had ever released. They weren’t footnotes to a career; instead, they expanded our understanding of the scope and depth of his work. Since then, the series has continued, mostly with live albums (filling in key uncollected bits of the mythos, notably, a strikingly vibrant and cacophonous two-CD account of the manic Rolling Thunder Revue). There was also another three-CD set of outtakes and unreleased tracks from the latter half of his career, Tell Tale Signs, interesting but not essential. The Basement Tapes Complete takes us up to Volume 11. (And brings, by my count, the total Bootleg Series disc total to 24.)

The Basement Tapes’ air of mystery and importance comes from two separate things. The first is that they were recorded at the very start of Dylan’s withdrawal from his stardom, and so chronologically, the next step in a career that had just seen the release of Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited, and Blonde on Blonde, which is to say a period of some of the darkest artistry of the 20th century. Dylan had a motorcycle accident in the summer of 1966; how severe it was has never been definitively established, but if nothing else, it served as an excuse for the star to get out of the celebrity fever-dream he’d been experiencing (see: “Desolation Row”), raise a family in peace, and explore some other musical directions. What the public saw over the next few years was limited: Almost no concert appearances, and a musical left turn: three or four albums of pared-down, largely acoustic, country-ish stuff, John Wesley Harding, Nashville Skyline, and New Morning. This work gradually gave way to a few years of utter chaos. (Dylan released a catastrophically informal two-record set, Self Portrait; soon after, his label Columbia vengefully put out Dylan, an even worse assemblage, after Dylan left the label.)

The second issue was the nature of the music itself. Here’s where Sandburg’s “things of the heart and mind” come in. Those next few Dylan albums were acoustic-based — a bit out of step with the state of pop at the time, but defensible — but were also a little tepid. His fans sing the glories of all three, and few will sneer at “All Along the Watchtower,” “Lay Lady Lay,” or “The Man in Me.” But the records are lyrically thin, and while not entirely humorless, they’re something less than jaunty and, in the end, bear little sign of the psychic power of Dylan’s earlier acoustic work. This music with the Band, though — this was a left turn as well, but into unknown and much more alluring and exciting territory. The incidental figures of Dylan’s colorful and logorrheic works — the debutante, the Mystery Tramp, etc. etc. — now take center stage, with Tiny Montgomery, Mrs. Henry, and other shady figures becoming the subjects of songs. The messages they deliver, or the stories told around them, in almost every case do not reveal themselves to logical analysis. Phrases like “Yea! Heavy and a Bottle of Bread” are sung out lustily and sail up to the ether, defying interpretation. Most distinctive, there is an aura of good humor, relaxation, and goofiness; in a word, fun. As for the music, it was a striking amalgam — even by the standards of the godforsaken amalgam that had created rock and roll. There were 19th-century songs, folk ballads, pop covers, and, most important, a huge new batch of Dylan songs in which all of those previous musics were gently, sometimes goofily, leveraged against his roiling talents. And since the place where this creativity was unfolding was a relaxed and unpressured one — and the works not intended for commercial release — the singer and his bandmates were free to see where the music took them. In other words, the songs weren’t an end in themselves. They were a process.

This collection supposedly has all of them. Those new to the songs should remember that we take for granted the artistry that goes into great pop and rock records; the romanticized notion of home recording aside, the sound of five or six guys playing in a sitting room, or an actual basement, creates an entirely different feel. It’s the sound of a group en masse, unbalanced, and sometimes muffled. The singer is finding his way through songs, testing timbre, phrasing, and tone; the guitarist and keyboardist are conjuring fills and chords; and the rhythm section is trying to find a compatible groove. Dylan’s lyrics, too, are ragged even by his standards. In sum, the result is occasionally off-putting and — though it is probably heretical to say it — not even consistently listenable. These aren’t songs of the sort on Vols. 1–3 or Tell Tale Signs — i.e., tracks recorded by a great artist that might have appeared on a record but for whatever reason didn’t. They are a step up from a jam session but several steps below recordable material, so they aren’t in the strictest sense enjoyable to listen to the way most rock music is.

The big find here is “Wild Wolf,” which, to my knowledge, has never been heard before; brooding and impeccably arranged, it is utterly sensational and unlike anything Dylan had recorded up to that point; it contains all the nuance and power he would (unsuccessfully) go for on the moodier tracks on Street Legal ten years later. (As for the title, you’ll remember the line from “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”: “I saw a newborn baby / With wild wolves all around it.”) There are a few other close-to-first-rate unreleased songs here, though fans are familiar with them: “Sign on the Cross,” which I guess would be classified as a gospel song, is sung feelingly, and line after line — notably the portentous “Now, when I was just a bawlin’ child / I saw what I wanted to be” — stays with you. “Silent Weekend,” a quirky 12-bar blues, has a fairly coherent arrangement and builds up to a fine, slow boogie. “I’m a Fool for You,” with its heart-bursting beginning, is an intriguing mix of romantic lyrics and Dylan’s grandest melodies; but the two takes here last just a minute or so each. (Forgive the deflating ‘90s reference, but it’s kind of like a Guided by Voices song, if Guided by Voices had had something to say.)

Among the lesser delights: a deceptively simple “Wildwood Flower” (listen, and you can hear a pretty effective bass line below the ringing autoharp; no records were kept during the recordings, so the personnel is lost to history); “The French Girl,” winsome and sad; “Santa-Fe,” whose delightful melody would have improved John Wesley Harding mightily. There’s also several CDs worth of much less compelling stuff, rambles through material old and new, like wan versions of the Canadian folk classic “Four Strong Winds,” the American folk classic “Blowing in the Wind,” the ‘50s doo-wop hit “Silhouettes,” and “The Auld Triangle,” by the doomed Brendan Behan; goofs like “Teenage Prayer”; odd jams like “Jelly Bean” and “Any Time”; so-so country stuff like “I Forgot to Remember to Forget Her”; even a growled take on the folkie-spiritual “She’ll Be Coming ‘Round the Mountain When She Comes.” “Come All Ye Fair and Pleasant Ladies,” I’m sure, is a priceless bit of song excavation, but from the falsetto yodeling at the beginning to the noodling guitar, it’s not that interesting to listen to; ditto for “Rock Salt & Nails,” whose traditional meanings and overtones are sunk by the sameness of the performance and the droning nature of Dylan’s singing.

The first authorized Basement Tapes included more than a half-dozen Band songs sans Dylan; two of these were co-written by Dylan and remain the standout tracks on the original release. Here we finally hear Dylan’s vocals on arguably the two major songs he produced that year, “Tears of Rage” (which he wrote with Richard Manuel) and “This Wheel’s on Fire,” written with Rick Danko. They may be throwaways, or they may be evidence of the direction Dylan’s songwriting would have turned had he not so plainly desired to tamp down audience expectations on his next few releases. The former, a wailing monologue of betrayal from a father to a daughter, reverberates here across three different takes. This too is heretical to say, but I think it’s an unfinished song; Dylan in his revved-up period reveled into the absurdist and unexpected U-turn of phase, but a key couplet in the first verse —“To wait upon him hand and feet / And always tell him no” — to me is just contradictory and, as a result, distracting. (To wait on someone “hand and feet” is to do whatever he wants; it doesn’t make sense to then say someone is saying no.) But those are part of the blemishes we accepted on that album; and here we have the opportunity to hear Dylan sing lead on the track, passionately and firmly, with overtones of vulnerability and pain completely foreign to his flinty, poised persona to that point.

In the end, your mileage with The Basement Tapes, as a consumer product, will vary. The whole eight-inch square package — with six CDs, a book with two sets of notes, and another book of photos from the era — is a gem, the most lavish Dylan reissue yet. (It should be for $120!) The only thing missing is a scholarly exegesis of each song. (A fairly definitive one was provided by Greil Marcus in Invisible Republic, now republished as The Old, Weird America.) There’s a two-disc assemblage of alleged highlights being released as well, but it lacks “Wild Wolf” and so can’t be taken seriously.

It’s possible that the Basement Tapes have been a little too revered. Now, it’s true: Dylan was wrenching his career off the track it was on. (Or, as the musician and author Sid Griffin rather ornately puts it in his liner notes, “The singer saw a light as bright as Saul witnessed on the Road to Damascus when he fell to the ground blinded.”) But I don’t think music — performing it or listening to it — is a particularly eleemosynary act. I don’t quite buy the ascetic purity argument advanced by Griffin here because I don’t have a problem with modernity. If they all wanted to get away from “Mammon’s temptation and distractions,” they had the money to do so; but I don’t see anything morally or aesthetically superior in the act of social and musical retreat Dylan and the Band embarked on. Dylan himself might have said he was sick of the raucousness in the streets; that’s a fair position, particularly given the blistering blender o’ fame he’d just been put through. But let’s not forget what a lot of the raucousness in the streets was about, not to mention the beatings a lot of the people creating that ruckus were given in return.

What remains is the songs. These are mostly, as Carl Sandburg wrote about the ones he collected, “singable songs”; at their best, they are works that take singer and listener into a different world, an American place both spooky and joyful. Marcus, in Invisible Republic, has a lot of fun with “Lo and Behold,” which is apparently a ribald and dense amalgamation of dark themes in American music. “Tears of Rage” will always rip at the heart of anyone who delves into it, and “This Wheel’s on Fire” remains an intensely moving valedictory. Sandburg caught some of the “old weird” feel of this music in the marvelous introduction to his book. Of the songs he collected, he wrote, there is a “human stir throughout.”

In prose that is positively Dylanesque, he describes his collection in words that capture both the Basement Tapes and Dylan’s own body of work: “Blasphemies from low life and blessings from high life for baritone and soprano are brought together. Puppets wriggle from their yesterdays and testify. Curses, prayers, jogs and jokes, mix here out of the blue mist of the past. It is a volume full of gargoyles and gnomes, a terribly tragic book, and one grimly comic. Each page lifts its own mask.”