News flash: Kim Kardashian didn’t invent the butt. Follow behind as we take a quick spin through the (admittedly quite Eurocentric) tale of Butts in Art History. Anne Hollander, author of Seeing Through Clothes, which rocked both academia and the art-aficionado world when it was published in 1975, thinks a lot about nudity. She observed: “Buttocks, like other projects, were assimilated into total harmony. But they were obviously also admired separately.”

Everyone knows that the first object generally taught in Art History 101 as a sign of humans being self-aware enough to model their own image is Venus of Willendorf. (Jeff Koons is obsessed.) No one could handle all that jelly — and she’s only a four-inch-high figurine! Leave it to the Greeks, however, to take the ass homage to the next level — and the set the standard for butts to come. And much of that is owed not to a painter or sculptor, but to Aristotle. While he may not have been a certified Ph.D. in rumpology, he instead wrote the book on perfection. Guess what? Not only did he write that perfection was idealized in the human body, but the shape that that constituted, as he wrote in Physica, “the perfect, first, most beautiful form”? Oh, the sphere.

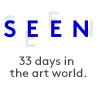

Take a look at classical art — one could bounce a quarter off those naked buns of the Kouros, seen below. As Hollander writes, “The masculine backside has even more readily lent itself to specialized erotic preoccupations because it thrusts itself on the attention separately.” In the Renaissance, it was thought that the many tight ends in Luca Signorelli’s work were what caused the dudes to be Damned to Hell, or even why Michelangelo’s David had the Italian court blushing (it’s certainly not his too too-big head and hands, or his too-small man-bits). One would think the that all those man-butts would get boring after a while. But nope. Jean-Louis David romanticized his male figures by putting the ass on blast, front and center, in his The Intervention of the Sabine Women. And the tradition only continues through Thomas Eakins, whose (slightly) pedophilic pictures of young boys in swimming holes came to define pastoral Americana in the late 1800s, which in turn influenced major butt enthusiasts such as David Hockney and Robert Mapplethorpe.

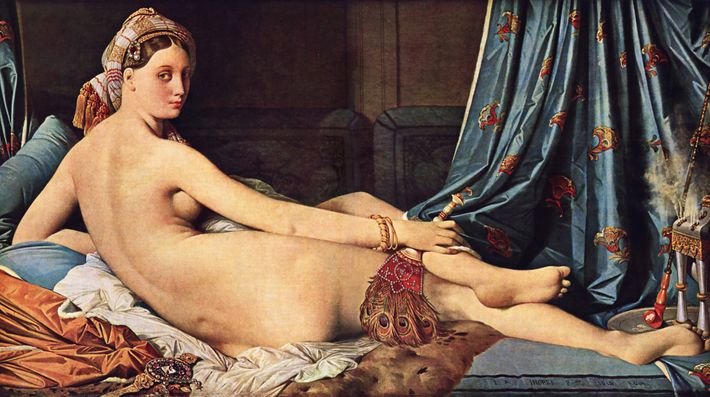

We women, on the other hand, have always had a more complicated time when it comes to our bodies. As seminal art historian Kenneth Clark wrote in The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, the nude form is “a means of affirming the belief in ultimate perfection,” and women’s bodies are an inherently erotic vision of ideal beauty (that obviously shifts between cultures). Much of feminine butt-play is owed to two major artists. The sumptuous sculptor Bernini was fond of featuring handsy men, as in the Rape of Persephone, which shows Hades fondling the ripples of the goddess’s flesh. On the flip side, Peter Paul Rubens (who is responsible for that adjective Rubensesque) allowed white people to become comfortable with the idea that a big booty is everything. Rubens messed with the Greeks’ whole delicate-harmony thing, and from that point forward, junk in the trunk was seen not as disruptive, but as distracting — in the right kind of way. In 1649, Velázquez rounded out his belle’s curves in Rokeby Venus; as did Ingres, in Odalisque, in 1814. There’s Antonio Canova’s Reclining Naiad from 1819–24, and William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s The Nymphaeum, from 1878, which is just one big panoply of humps.

But then the 20th century happened, and everything changed — butts included. Pablo Picasso was the first to deconstruct the butt with Desmoiselles d’Avignon. Marcel Duchamp played a joke with his doodled Mona Lisa L.H.O.O.Q, which quite literally translates from the French to, “She’s got a great ass.” Yves Klein made his bootylicious Venus blue. And the Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning gave weight to the thunder thigh with his “Women” series (probably prompting the Queen song “Fat Bottomed Girls”). Fernando Botero has a similar eye — his women languorously lie about in their voluptuous glory. Of course, Carrie Mae Weems, Kara Walker, and Kehinde Wiley have long championed the black booty in their work — and it must be cited that the black body’s representation throughout art history can be summed up in the Hottentot Venus caricatures, which depict South African showgirl Saartjie Baartman in a most uncomfortably objectified manner. Many black artists have responded to these colonial images and combatted the cartoonish Western fetish that the Hottentot images proliferated.

But now, in the contemporary realm — where anything goes — we must conceptualize the butt. Take Jeff Koons’s Ilona’s Asshole. Or Cindy Sherman’s Disgusting Butt. Then there’s Ryan McGinley, who, in a post-Mapplethorpe, idealized, erotic world, has made the female and male butts both innocuous and innocent, blanched of any overtly erotic tones — even at a time when butts are thought to still break the internet.