Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations, and you should read as many of them as possible.

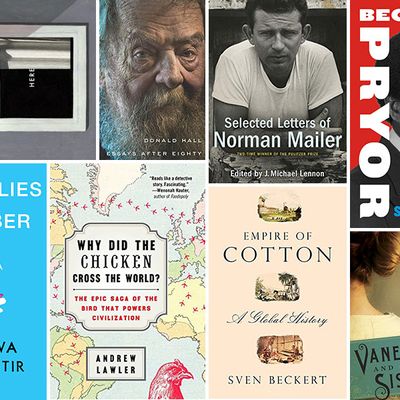

The Reckoning: Death and Intrigue in the Promised Land—A True Detective Story, by Patrick Bishop (Harper, Dec. 2)

No group has a monopoly on terror. Bishop, a military historian, makes that painfully clear in recounting the fall of the Stern gang — Zionist terrorists marginalized during the British mandate but now valorized by a hard-line Israeli leadership. The author isn’t a partisan, nor does he absolutely confirm that Avraham Stern, the insurgent group’s charismatic leader, was killed in cold blood by a colonial policeman in 1942. What he does, thanks to tireless research and powerful storytelling, is show how a ruthless murderer of civilians became an unnecessary martyr.

The Selected Letters of Norman Mailer, edited by J. Michael Lennon (Random House, Dec. 2)

For fans of the novelist-pugilist, this posthumous fruit of his correspondence — 716 letters out of almost 50,000 — is indispensable. For anyone interested in the intellectual battles of the past 60 years, it provides a detailed road map of the controversies and egos involved. (Correspondents included Jackie Kennedy, Marlon Brando, Henry Kissinger, both Clintons, and pretty much every white writer of his generation.) And for the rest, it’s a subtle document of an unsubtle man’s wit and erudition, even (or especially) when it’s wielded as a weapon.

Butterflies in November, by Audur Ava Ólafsdóttir (Black Cat, Dec. 9)

Anyone who’s fallen inexplicably in love with a European road-trip story will be vulnerable to this fictional journey around Iceland’s Ring Road, as taken by a very recently divorced childless translator and her friend’s deaf 4-year-old son. (In France it was a best-seller.) Between the high jinks and before the book’s coda of 47 recipes (sheep’s head jelly?), the dark weight of the novel creeps in as our narrator confronts her own youthful traumas and learns to reattach herself to the world.

Essays After Eighty, by Donald Hall (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Dec. 2)

“Poetry abandoned me,” writes the former U.S. poet laureate in the second of these astringent and vivid essays; the “blast of hormones” required for the “imagination and tongue-sweetness” of verse vanished at 85. But Hall’s prose stayed strong, deep into a stage of life so rarely documented in a graying nation fixated on youth. Having become only more himself — impressively bearded, sedentary, sparing of actions and words — Hall ponders the seasons, smoking, divorce, mourning, and death in language as laconic as his poems.

Becoming Richard Pryor, by Scott Saul (Harper, Dec. 9)

Saul arrives fashionably late to the story of Pryor’s wild life: A biography and a documentary came out last year. But he’s the right writer for the job, an eloquent synthesizer and a first-rate analyst (he’s especially good at breaking down everything about a classic bit: how it was built, why it landed, and where it came from in Pryor’s tormented history). In the wake of the downfall of moralist-in-chief Bill Cosby, it pays to follow Saul into the brain of the painfully honest hot mess who truly expanded comedy’s borders.

Here, by Richard McGuire (Pantheon, Dec. 9)

With one deceptively simple conceit, McGuire renders the possibilities of the so-called graphic novel literally infinite. Here depicts one room in a century-old house across various years, collaging images over two-page spreads (so, for instance, windows from 1932, 2008, and 1923 overlay a scene from 500,000 BCE). The pleasure is in the execution — in what McGuire pulls out of the limitless chaos of time. Building on themes and micro-narratives, he creates comedy and tragedy out of cosmic slices. It reads like a map of the mind of an exceptionally artistic physicist.

Vanessa and Her Sister, Priya Parmar (Ballantine, Dec. 30)

The literary-historical novel is a tricky thing: too freewheeling and it’s fanfic for English majors; too dutifully true and it’s pointless. Parmar uses the familiarity of her subject, the Bloomsbury Group, as a head start, burrowing deeper into the minds and mores of England’s liberal vanguard (especially narrator Vanessa Bell, the sensible painter chronically overshadowed by her sister Virginia Woolf). The plot — as pretzeled as Bloomsbury’s round-robin of love affair s— unfolds at the steady pace of time, in crisp period prose, and rarely feels inevitable.

Empire of Cotton: A Global History, by Sven Beckert (Knopf, Dec. 2)

Why Did the Chicken Cross the World? The Epic Saga of the Bird That Powers Civilization, by Andrew Lawler (Atria, Dec. 2)

Nearly 15 years into the genre of Books About Things That Changed the World, it’s difficult to even title such a study without skirting self-parody — as both these titles do. But the books redeem themselves in distinctive ways. Beckert, author of The Monied Metropolis, focuses on “the unity of the diverse,” and the fabric fits. Cotton was built on the rough trade of mercantilism, boosted by slavery, powered by industrial England, and finally dispersed among the cheap labor pools of the developing world. If his chronology feels a bit heavy, let Lawler’s silly-titled book be your palate-cleanser. Not that it’s pure fluff (forgive both our puns). The poultry economy is far too brutal for that: a factory system that repays our most plentiful domesticated animal, 20 billion strong, with remorseless cruelty. But the prolific science journalist also follows his fowl to stranger places — eugenics experiments, evolutionary detours, economic digressions, village anthropologies, and even space exploration. Lawler is an entertaining guide with an easy touch, whimsical but never random. Also, chickens are inherently funny.