I met Jennifer Rubell 20 years ago at a birthday party, and a week later, she’d invited me over to dinner at her Upper East Side apartment. At the time, we were both 24, and though I knew she was Steve Rubell’s niece, I didn’t know that she was the daughter of celebrated art collectors. Or that, together with her family, she was a burgeoning hotelier (about six weeks later, she’d relocate to Miami, where she’s lived for the next ten years, to help her brother Jason run the Albion Hotel in South Beach). Or that she threw her first dinner party at 9 — and would eventually attend the Culinary Institute of America; intern for Mario Batali at the Food Network; become renowned for her extravagant dinner parties, which led to a writing career as a food and home-entertaining columnist for the Miami Herald and Domino; and author Real Life Entertaining: Easy Recipes and Unconventional Wisdom. She was the first gourmand I’d ever encountered. All of our peers at that time used their ovens for storage and ate out at places like San Loco Taco and Dojo’s café — which was totally acceptable — and here she was, with a tricked-out kitchen, making dinner for us like it was nothing. We reconnected the year after she returned to New York, in 2009. She’d become a mother and, as I featured in the magazine in 2011, an artist, using food as her medium. More recently, Rubell and I got together a week before Art Basel to talk about the violent spectacle of the Perfoma fund-raiser, the decidedly feminine aspects of her work, and her brief departure from working with food.

Let’s talk about the fund-raising dinner you curated at Performa on Election Night 2014. At the end of the dinner, guests shattered everything — the plates, the tables — with hammers on the night the GOP was seizing control of the House and Senate. Was this some kind of political statement?

Politics is not of much interest to me — it’s so black and white. A lot of what I deal with has to do with the parts of ourselves that we wish weren’t there, that, when you declare yourself to be black or white, the parts that you leave out. I think art in general deals with those bits and refuses to leave out the parts that would be more convenient to ignore. I think that’s an important function of art versus politics. The dinner was only 370 people — that’s very small for me — and it was a very, for lack of a better term, A-list crowd.

Whom do you consider to be A-list in this context?

To me, there’s no worse term than A-list. But it was Klaus Biesenbach, Marina Abramovic, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Mario Batali. Art people, music people, film people. So you have all these people and they’ve been everywhere, they’ve seen everything. Any gala, fund-raiser, dinner is an inherently decadent action, and I feel like making that explicit: The destruction and exuberance of waste is a part of being honest with what’s going on. We as humans, certainly we as Americans, love violence and death and destruction. If we don’t love it, why are we constantly making it? Whether it’s consuming virtual violence or creating conditions of violence around the world or celebrating violence, violence brings with it a lot of pleasure for us, and it’s true in a very personal sense for us, too. So the guests were sitting at this pedestal all night, where this intense feast unfolds. And then they realize that it’s been there to destroy the whole time.

So how did the dinner spectacle play out up until that moment?

There were these rubber chickens hanging in the middle and everybody was sitting on one side of the pedestal tables facing them. I was very interested in the idea that the center of attention is whatever you want it to be. Underneath the rubber chickens was a pedestal of deviled eggs. You beat the rubber chickens with these sticks, and smoked paprika came out on them. People found their seats at the pedestal tables. And then this intense feast came out: pheasants with feathers, suckling pigs, and whole giant parsnips — that kind of thing. These guys in these assless chaps, jock-strap, flag-bearing contraptions — they were designed by this incredible artist-tailor, who sewed each one onto their bodies and cut them to glorify their asses — the “brigade,” came out in their flag carriers with a whole stalk of roasted Brussels sprouts, and people had to slice off the Brussels sprouts. It was a scene of hilarity and decadence. Meanwhile, people have been sitting at these white pedestals on sawhorses the whole night, and these hammers materialized around the room, and people started breaking the tables, and inside the tables popped streamers and chocolates and candy and cookies. So this joyful destruction was sitting there the whole time. Oh, when people came in, the brigade had flags that had the number of each table, and then once everyone was seated, they took the flag off and wrapped it around this woman to form a kind of vaginal cloak, and they put a pot of soup in front of her and she very humbly served soup to everybody at the table. The artists who were being honored were being asked to serve. Because the only honor you can really give somebody is the opportunity for humility. And a lot of the artists who were being honored actually refused to serve. They thought it was demeaning and humiliating.

For 13 years, you’ve done a breakfast for Art Basel. What did you do this year?

Fifty cakes. It’s in celebration of my parents’ 50th anniversary. [Rubell had her parents, and 48 servers, all dressed in black, spoon-feed the 50 wedding cakes — in chocolate, strawberry, and vanilla — baked fresh that morning to the guests at the breakfast.]

Every year you come up with a new concept.

Yes, and every year, I think I’m going to—

Give up and order pizzas?

Yeah. And even if I ordered pizzas, it’d be a whole thing. But you know, you’ve seen this in your own life, you put one foot in front of the other, and then suddenly you’ve been doing it for 13 years. Literally, today I got seven emails of the absolute craziest opportunities to do totally different projects everywhere. And it only comes because, after a certain amount of time, you’re the only one who does what she does — I wouldn’t know whom to call other than myself if I were doing that kind of thing.

You’ve always had a relationship to food, to art, to hosting, to curating — your parents being collectors, and you famously throwing your first dinner party at 9. Plus, of course, your uncle Steven, who was the consummate host and scene-maker at Studio 54. And now you’ve figured out a way to fuse all of it into an art form.

I think all artists make work from a place of instinct. And then you figure out what it is that you’re doing and why, and you frame it, and you understand it. Art that doesn’t is usually very, very bad. Because it needs the openness that instinct has. My work can seem really broad, and I’ve been thinking about what connects it to each other: It’s in the realm of the feminine arts. So whether that’s food, entertaining, wanting to get married, having a child, being someone’s muse or model — any of those things, they’re all completely gendered feminine.

It’s also all about engaging.

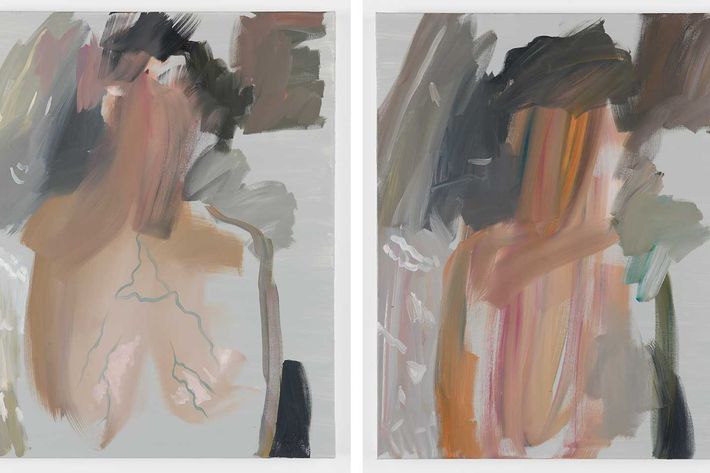

Yes, but even engaging is a fundamentally feminine role. And in every case, it’s been about how to deal with all of those acts and emotions and inclinations in a way that has the permanence and long-term presence of the more traditionally male media of sculpture, painting. Performance has been male and female. It’s where all the work turns around. So whether it’s giving somebody the opportunity to slip their finger through an engagement ring (Engagement), or like Portrait of the Artist, where people are crawling into my belly, or dealing with the fact that the model is the artist and shares authorship of the work and isn’t just somebody who inspires and supports and fucks the painter. I started doing the painting project, where I was posing every day in the studio with Brandi Twilley, who paints me. Together, we are Brad Jones — that’s the name of our collective. In each instance, it’s insisting that this profoundly feminine experience, which is the supporter, the defender, the mother, the hostess, the helper — be a role that is as dead serious as the role of a painter. For me that’s the crossroads of all my work.

With these last few projects, you took a break from working with food.

I didn’t do food stuff for awhile. And Brandi and I were creating all of this intensely traditional durable work. I think at some point I couldn’t take how ephemeral food was. Somehow doing the paintings made me crave the ephemeral work. It was a totally involuntary inclination. So now I have a bunch of food projects coming up.

Can you talk about any of them?

I don’t know if I can. I’m working on a project in Canada in June. And another that I can’t talk about. And then I’m working on a sculpture show. I have a piece that Eric Fischl curated at the FLAG Art Foundation, it’s one of my Nutcracker pieces. It’s so awesome to see it there, in the company it’s in: the Chapman brothers, Laurie Simmons. And I’m still posing for Brandi. I feel so lucky that we came together. I don’t think I’ve ever had as deep a collaboration in any aspect of my life. It’s such good fortune that it’s with her. I never lost interest in food. I think the food projects take so much out of me, they’re emotionally and physically so intense, and I just needed a break. I think I felt resistant to do anything that was going to be gone the next day. But that disinclination is totally gone.