“We turned down a million dollars to make a song for one of the Twilight movies,” says John McCauley, the front man for indie rockers Deer Tick. “Those movies are terrible,” mutters keyboardist Rob Crowell, lolling on a couch in a plush townhouse in Clinton Hill, a giant Sour Patch Kid–shaped neon light hanging on the wall behind him. On this late afternoon in December, McCauley and his bandmates are in New York to play a string of six consecutive sold-out shows at Brooklyn Bowl—a celebration of Deer Tick’s decade together. A documentary is being filmed to memorialize the milestone, and the following night, New Year’s Eve, they’ll be joined onstage by Stevie Nicks for a rendition of Fleetwood Mac’s “Rhiannon.” It’s all evidence that even though Deer Tick has never quite made it big, they’ve done all right.

Of course, this is the rock business in 2015 (indie rock, no less), which means all right could be a whole lot better. Normally when they visit New York, Deer Tick dips into their touring budget for lodging—Williamsburg’s casually posh Wythe Hotel has sufficed in the past. But this week, they’re stationed at the Brooklyn Patch, a tricked-out artist crash pad paid for by Sour Patch Kids—a brand with far more experience selling candy to adolescents than putting up rock bands.

“It’d be fun to write a jingle for, like, Swiffer WetJet,” McCauley says aloud, tossing off idle thoughts about business opportunities to no one in particular. In 2015, this kind of thinking is extremely common. In New York, Red Bull and Converse have decked-out recording studios that young artists can use at no cost, while Mountain Dew boasts its own label for smaller acts. But despite the proliferation of brand-band unions, these deals remain, in almost vestigial fashion, an easy target for derision: “ ‘Indie’ Bands Sell Out Just to Sleep in Corporate-Run Crash Pad,” Gawker sneered in a November post about the Patch.

Rather than take offense, Deer Tick shrugs. “It’s the world we live in,” says guitarist Ian O’Neil, sunk into the cushy couch. “I get giddy about such funny opportunities.” The band’s drummer Dennis Ryan chimes in: “I buy immense amounts of Sour Patch Kids on the road.”

“When all is said and done,” adds McCauley, who will sleep back at his Manhattan apartment tonight with his wife, singer-songwriter Vanessa Carlton, “Deer Tick supports Sour Patch Kids, with or without this wonderful house.” His bandmates howl with laughter.

As spiritually dissonant as it may still seem for a band beloved for its rowdy, drunken clamor to be, almost literally, in bed with one of America’s leading gummy-candy brands, agreeing to stay here isn’t exactly making a deal with the devil. With the Patch, which was launched in late September, Sour Patch Kids offers touring artists the chance to use these capacious digs for free, under one simple condition: that when they upload digital content from the house—tweets, YouTube videos, Instagram photos, Tumblr posts—they use the hashtag #BrooklynPatch. The longer the stay, the more content is expected. There are no formalized conditions outlined for this exchange, so an especially irreverent artist could technically get away with uploading nothing. “But it wouldn’t be cool,” says Jesse Kirshbaum, head of Nue, a creative music agency tasked with coordinating Patch guests. The line between cool and lame is, as always, a fine one, and Sour Patch, to its credit, is trying to be subtle. So subtle that the artists might feel okay taking shots. The day before my visit, Deer Tick uploaded a blurry Instagram of Ryan inside the house, captioned as follows: “Better call an #uber to leave the #brooklynpatch to go to #brooklynbowl to play #devo!” the post read. “Come on out and help us #sellout!”

The idea for the Patch was hatched last year as part of a new marketing initiative from Mondelez International, the parent company of Sour Patch Kids (along with brands like Cadbury, Trident, Halls, and Oreo). Like a growing number of brand campaigns, the project eschews traditional marketing and advertising strategies in service of a grand, elusive goal—to develop authentic-seeming connections to pop culture and, by some Rube Goldberg mechanism of influence, spur independent-music fans to buy more sour-dust-coated gummies. “When artists come here, they’re eating Sour Patch Kids, they’re talking about Sour Patch Kids,” says Farrah Bezner, a marketing director at Mondelez. Her goal, she says, is for Sour Patch Kids to become “a part of conversations in culture.”

“Given the condition of the music industry, I think most bands would jump at an opportunity like this,” McCauley says. Well, not all bands—initially, members of the Patch’s team claimed it would host Tame Impala, one of today’s vanguard indie acts. That turned out to be false, a fact that made news on its own. “Nothing against the Sour Patch Kids, we hear they’re delicious. We’re just not staying at their home,” the band’s manager wrote in a firm statement. But by and large, artists are jumping at the opportunity. The Patch has been solidly booked since it opened, and Mondelez has readied an outpost in Austin in time for South by Southwest. “What we heard is that life on the road is tough,” Bezner says. “So we essentially wanted to create a pit stop.” The aim is to focus on “emerging” artists, most of whom are chosen and solicited to stay in the house by Nue and Sour Patch Kids.

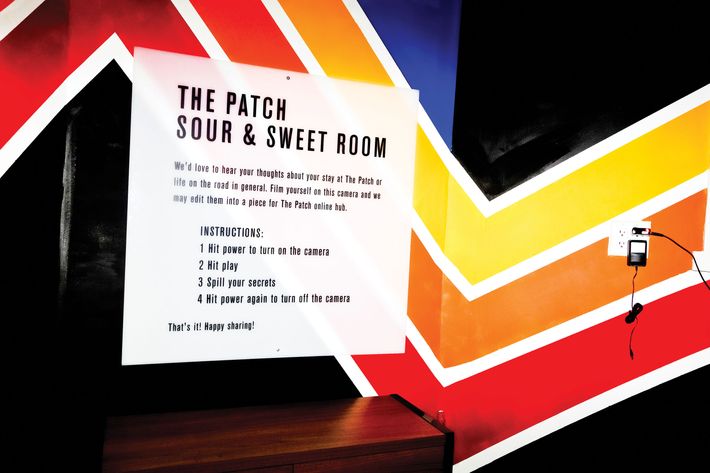

To get to independent-music fans, Sour Patch Kids is first trying to woo independent artists by making them comfortable during their stay at the Patch, while retaining some of the unflashy sensibilities that ostensibly make the musicians cool to begin with. The rented four-bedroom, three-story house is almost opulent, but dappled with overt nods to upscale bohemia. Designed in part by an “experiential marketing” firm called the Participation Agency, the house boasts flat-screen TVs and locally roasted coffee; a washer-dryer and a graffiti-covered makeshift basement recording studio (“The Patch Lab”); a giant, luxurious all-glass shower and a bin of organic lip balms; an endless supply of Sour Patch Kids candy and a pile of custom Sour Patch Kids temporary tattoos created with vegetable-based dyes. Each bedroom has a vaguely candy-flavored name (the Green Room, the Red Room). And there’s a guy named Geoffrey living nearby, a sort of Sour Patch superintendent, who’s on call 24 hours a day in case anything goes awry. The exact address is kept secret, and artists are asked not to geo-tag any of their content. It appears no expense has been spared, but for Mondelez—valued last year at over $59 billion—the costs associated with the Patch are likely equivalent to a rounding error.

That’s not to say that Patch is a free-for-all. In the homey living room is an ornamental fireplace, above which looms a giant black-and-white drawing of a rose and thorn by tattoo artist Mina Aoki. On the mantel sits an inconspicuous sign reminding guests of exactly what they’re not allowed to do in the Patch: no noise after 11 p.m., no illicit drugs, no guests who haven’t been approved by the Patch overlords. All of which is kind of a shame, because the Patch seems like a pretty killer spot for a party.

A few weeks before Deer Tick’s arrival, though, an underground rapper from Seattle named Nacho Picasso is determined to prove that the Patch has room for some anti-Establishment rock-and-roll rebelliousness. “They’re lying. They’re trolling us,” says Nacho as he reads the sign. He turns his back on the house rules and bounds into the kitchen. In his loud Givenchy sweater, he strikes hammy poses in front of a wall of glass jars filled with Sour Patch Kids. “Can you get a picture of me, man? My sweater looks good,” he says to his manager, Jonathan Moore. “Gotta wake up and do my Brooklyn Patch shit because I know I’m gonna get high and forget to do it later,” he adds and proceeds to upload a photo to Instagram, which will eventually rack up more than 400 likes, captioned, “Sour patch for breakfast … Yikes! #brooklynpatch #Givenchy.”

The last time he was in New York, Nacho stayed in the high-end Thompson LES on Vans’ dime. This time, he is pleased to crash at the Patch, especially given his genuine long-standing enthusiasm for Sour Patch Kids. He knew he wanted to visit New York to finish a project he’d been working on with Brooklyn producer Harry Fraud, and when Moore learned about the Patch through the brother of Nue’s Kirshbaum, he jumped at the opportunity. Sour Patch Kids were already on Nacho’s tour rider, after all. And he wouldn’t stay at just any candy-branded house. “If it was Snickers,” he assures me, “I’d be like, no.”

Nacho makes himself a cup of green tea while Moore takes an occasional pull from a vape pen. Then he orders delivery fajitas. At one point, a beautiful girl with blue hair and a septum piercing wordlessly moseys into the kitchen, then just as wordlessly moseys out. As he waits for Fraud to arrive, Nacho puts the Seattle Seahawks game on the giant TV in the basement and periodically mentions that he needs to buy some weed he can smoke. (Right now, they’re relying on G Pens and THC-infused gummy candies.) They joke about what might happen if they planted a funny gummy in a bowl of real Sour Patch Kids. “Somebody would come into the Brooklyn Patch and get fucked up!” Nacho says, delighted. “Some cool guy who doesn’t even smoke.”

Despite the potential for mischief, the activities at the Patch remain, from what I can tell, pretty PG. Deer Tick’s most adult behavior involved cracking open some Modelos and smoking cigarettes in the backyard. Nacho got stoned and had a couple of friends stay in the house. Atlanta rapper Rome Fortune, who shot a music video at the Patch during his stay in November, explains that “if you’re cool, stuff flies. As long as you don’t go in there trying to destroy stuff and going nuts, they’re pretty chill.” One of his tweets from the house read, “Who wants to come thru n hang w/us tonight?” but did not include the #brooklynpatch tag.

“It’s not, like, an oppressive or authoritarian vibe,” says Moore. It’s also not exactly the Chelsea Hotel in 1974. Despite the posted house rules, reps for the Patch keep emphasizing to me that the house is for accommodations, not parties. And they’re reluctant to let me into the Patch unchaperoned, especially after my solo visit with Nacho. (They’d found out about the THC-infused candy.) Sour Patch Kids is part of a giant corporation, and while these young, charismatic musicians make for ideal brand reps, they can also go south. In 2013, an advertisement that rapper Tyler, the Creator made for Mountain Dew drew widespread criticism for an off-color joke and was quickly yanked.

Brands seem to be figuring out that a good way to avoid the potential pitfalls of artist partnerships is to not really form partnerships at all. A video Nacho shot for Vans doesn’t even mention shoes. Red Bull doesn’t ask for any ownership or control over the music artists record in its luxurious Chelsea studios. The Patch is another example of this coy courtship—there’s no obtrusive signage outside the house, which is in a quiet Brooklyn neighborhood rather than the globally commodified hipster meccas of Williamsburg or Bushwick. No money changes hands, and the hashtag #brooklynpatch is, notably, brand-name-free. The Patch is amusing enough—like O’Neil says, it’s funny—that being involved doesn’t feel evil. In fact, the touch is so light that one must wonder: What does Sour Patch Kids actually get out of it? That artists are willing to link up with the brand probably says more about the changing sensibilities of “indie” than about the candy’s ability to penetrate the culture.

Sour Patch’s reasoning for why artists might be inclined to align themselves with its brand is equally fuzzy. “The sour-then-sweet personality,” says Bezner by way of explanation, “is very consistent with up-and-coming musicians.” Still, you’d have to hold some pretty outdated beliefs about the sanctity of independent art to believe the Patch is a soul-sucking force rather than just a goofy experiment. As Josh Rabinowitz, a director of music at Grey ad shop, puts it: “It’s a bitch to monetize your creativity. So why not associate yourself with a brand that’s not shoving itself down your throat?”

“But back to this selling-out thing,” Deer Tick’s O’Neil interjects after our conversation in the Patch living room has meandered elsewhere. “The only people I care about what they think are my peers,” he says. “And even then, fuck it. When I was like 15, I didn’t eat meat for a while. But then I realized that was more white privilege than anything else.

“The older you get,” O’Neil says, then pauses. “Everyone in this room is supporting some kind of horrible cause.” He points out that one alternative to corporate entanglement in the music industry is the record labels, which, in the old days, “would be like, ‘We don’t like how that song sounds, so you have to change it or we’re not putting out your record.’ ” O’Neil sees that as a far more insidious force than Sour Patch Kids candy, which, he admits, he can’t really enjoy, because he “doesn’t have the teeth for it.”

A few moments later, someone uploads an unremarkable photo to Instagram, captioned “Breakfast at #brooklynpatch,” of people gathered in the Patch kitchen eating bagels. Over the next couple of days, the band uploads two more photos that are a bit more direct—one features Ryan pensively holding drumsticks near a big bowl of candy, and the other shows two band members embracing as they close out their visit, one sporting a lime-green THE PATCH sticker. The hashtags on both—#thepatch instead of #brooklynpatch—are wrong, probably by accident. “What a time!!!!!” the good-bye post reads. “#thepatch #end.”

*This article appears in the February 23, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.