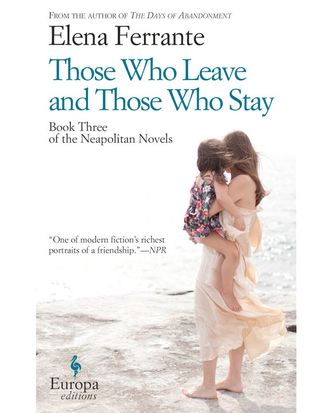

No author, certainly living and possibly dead, is both better and less known than Elena Ferrante, the pseudonym of a now-world-famous and also completely obscure Italian novelist. In seven brilliant, barbed novels narrated by women trying to carve out a place for themselves in a stubborn and eroding patriarchy, Ferrante has plumbed friendship and motherhood, art and work, money and class. But even as her fame has grown much beyond Italy, she has remained totally invisible to the press — and therefore to her readers. In the very few email interviews she’s given in the past, she’s hinted at the real origins of the deeply personal events and emotions in he work — without revealing much at all. “Page Six”–size speculation about her identity has swirled in Italy for decades and spread internationally in recent years, in tandem with her globalizing audience. (There’s even been a spirited metadebate recently about whether raising the possibility that she might actually be a man is itself a sexist question.) The latest of her four Neapolitan novels — which she considers one book — will be published in English this fall, under the title The Story of the Lost Child.

This month, Ferrante gave her first in-person interview, conducted by her Italian publishers, for an “Art of Fiction” treatment in the spring issue of The Paris Review. There was actually a touch more personal revelation in a December email Q&A with the New York Times, but there’s far more in the Review about her process and her evolving career. Here’s what we can add to the small body of knowledge about the real “Elena Ferrante.”

She was born and grew up “on the periphery of Naples.” As a child, she witnessed “crude family acts of violence.” She also experienced “the humiliation of abandonment.”

She may not still live in the area, but she has family there. “There was no particular need to meet in Naples,” the publishers write, “but Ferrante, who was in the city for family reasons, invited us” to interview her in that city.

Ferrante has written down her dreams since she was a child. “It’s an exercise that I would recommend to everyone.”

She doesn’t believe in memoir for its own sake: “It’s not enough to say, as we increasingly do, These events truly happened, it’s my real life, the names are the real ones, I’m describing the real places where the events occurred. If the writing is inadequate, it can falsify the most honest biographical truths.”

She spent years writing “more or less conventionally made stories about Naples, poverty, jealous males, and so on. Then all of a sudden the writing assumed the right tone,” which is when she decided to publish her first novel, Troubling Love.

People who have attributed her books to more than one author “are no longer attentive to style.” They’ve done so because “the decision not to be present as an author generates ill will and this type of fantasy.”

Ferrante told the Times that the ten-year gap between her first and second novels had to do with her worries about publicity. But here she gives a different explanation. She “worked a lot,” but it took a decade “to separate my writing from that specific book.” She adds, “Only with The Days of Abandonment did I feel I’d written another publishable text.”

Even then, she ran into trouble. Ferrante wrote the first two parts of that novel quickly, then agonized over the last part for months. “Even today,” she says, “I don’t dare reread the book.”

She internalized literature’s gender bias early on. “As a girl — twelve, thirteen years old — I was absolutely certain that a good book had to have a man as its hero, and that depressed me.” Even as she grew out of it, she still admired mostly male writers — Defoe, Fielding, Flaubert, Hugo, and the great Russians. But women’s literature “made me an adult” in her 20s.

The Lost Daughter is her favorite among her books, “the one I’m most painfully attached to.”

Ferrante cares a lot about the reader — to a point. “I publish to be read,” she says. And yet, “I don’t think the reader should be indulged as a consumer, because he isn’t one. Literature that indulges the tastes of the reader is a degraded literature.”

Her reasons for anonymity have evolved. At first, “timidity prevailed. Later, I came to feel hostility toward the media.” Finally, she savored the freedom it afforded her, and the idea that literature comes not from “some writer-hero” but from “a sort of collective intelligence.”

She expands a little on a personal influence: “The theme of female friendship certainly has something to do with a childhood friend of mine, who I wrote about some time ago” in an Italian newspaper.

She tries not to talk in detail to anyone about work in progress: “A plot twist can lose substance simply because I can’t keep it to myself and describe it to a friend. The oral story immediately destroys everything.”

The Neapolitan novels came easily. Ferrante wrote 50–100 pages a time without stopping to revise. Which is as it should be. “The greater the attention to the sentence,” she says, “the more laboriously the story flows.”

Still, she writes obsessively at the end, right up until the hour the book goes to proof. “There is nothing that can’t, at the last moment, end up in the story.”

She believes that “writing requires maximum ambition, maximum audacity, and programmatic disobedience.”