In 1994, Brent Staples, an editorial writer at the New York Times, wrote an account of Saul Bellow that was first published in The New York Times Magazine and then later as part of his memoir, Parallel Time. Raised in impoverished circumstances in Chester, Pennsylvania, Staples, who is black, described discovering Bellow upon his arrival in Hyde Park to attend the University of Chicago. Simultaneously in thrall to Bellow’s fiction and stung by Bellow’s fictional characterizations of black people, Staples “wants to lift [Bellow] bodily and pin him against a wall. Perhaps I’d corner him on the stairs and take up questions about ‘pork-chops’ and ‘crazy buffaloes’ and barbarous black pickpockets. I wanted to trophy his fear.” At the same time, “I wanted something from him … I wanted to steal the essence of him, to absorb it right into my bones.”

Staples’s Times Magazine article, as riveting and memorable as something by Bellow himself, caused an uproar, outraging Bellow’s friends and supporters and gratifying his detractors. The latter group increased exponentially one month later, when another disappointed Bellow-lover, Alfred Kazin, published his own autobiographical essay in The New Yorker. Kazin quoted a comment Bellow made to an interviewer in 1988. Addressing attempts to make undergraduate reading lists of literature more inclusive, Bellow had quipped sarcastically, “Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans? I’d be happy to read them.” When he heard that Bellow had said that, Kazin wrote, “my heart sank.” Though barely a peep of protest occurred when Bellow’s remark first appeared in print, Kazin’s reiteration of it, so soon after Staples’s magazine essay, provoked a frenzy of denunciation.

Bellow’s remark was insensitive. The attempt in the 1990s by academics and critics to open up undergraduate reading lists to new voices was a robust and healthy, if sometimes irrational, democratic development. Such a development was the result of, as Bellow liked to say, implacable trends in history, society, and culture, and Bellow the Big Thinker proved himself surprisingly unable to grasp them. The response to his bon mot was so virulent that Bellow had to take to the op-ed page of the Times to defend himself. “Righteousness and rage threaten the independence of our souls,” he declared with his usual vatic panache. His reputation never recovered.

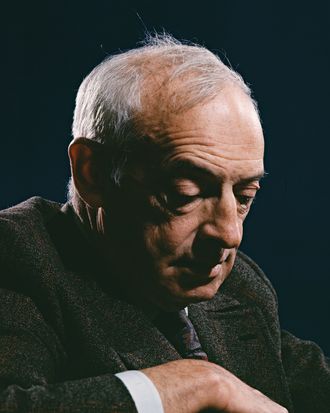

Bellow, who won more literary prizes than any other American writer — three National Book Awards, a Pulitzer Prize, and the Nobel Prize in 1976 — has always aroused strong emotions. John Berryman, an intimate of Bellow, dedicated a poem in his Dream Song cycle to him. Anne Sexton, also a Bellow friend and swept up — unromantically — into Bellow’s magnetism, used a passage from Herzog as the epigraph to her Pulitzer Prize–winning Live or Die. Herbert Gold, once a friend of Bellow, lashed out at him in his memoir, describing him as a solipsist “who banged on his high chair with his spoon.” Philip Roth presented a thinly disguised Bellow as a suave meganarcissist in the character of Felix Abravanel in The Ghost Writer. Salman Rushdie and Ian McEwan both wrote novels based on earlier novels by Bellow. Before becoming Bellow’s authorized biographer, James Atlas published a novel, The Great Pretender, that was virtually an effort to stylistically cannibalize Bellow’s identity. Reviewing the book in The New Republic, Sven Birkerts wrote that Atlas regarded Bellow as “The Father. Atlas would like to swallow him whole and be him — parricide by anthropophagy.”

Harriet Wasserman, Bellow’s former agent, wrote a passive-aggressive memoir about her famous client, who eventually jilted her for another agent. Mark Harris wrote a book about trying to become Bellow’s biographer, a book that was also, in the words of one reviewer, “an idiosyncratic account of [Harris’s] obsessive and ultimately frustrated efforts to get Saul Bellow to take him seriously.” In his memoir, Experience, Martin Amis recounts saying to Bellow, after Amis’s father has died, “You’ll have to be my father now.”

And yet many people under the age of 50 have barely heard of Bellow, if at all. Laced with magisterial generalizations about history and culture, Bellow’s fiction turned off readers and writers suspicious of intellectual abstractions and doubtful of the authority behind them. Bellow’s constant invocation of the conventional canon of great literature also fell flat. Younger readers were as hostile to the official literary pantheon as the young Bellow — the impecunious son of Jewish immigrants — had been to the Hemingways and Eliots of his day.

This spring, on the centennial of his birth and the tenth anniversary of his death, Bellow will burst from posthumous detention. A volume of his collected nonfiction is being published, as well as the fourth and last installment of the Library of America edition of his work. But the main event will be Zachary Leader’s biography The Life of Saul Bellow: To Fame and Fortune, coming out in May, which portrays Bellow up to 1964. Orchestrated by Bellow’s literary executor, literary superagent Andrew Wylie (who replaced Wasserman), this massive life by Leader, also Wylie’s client, is transparently meant as a corrective to the authorized biography published by Atlas in 2000, which presented Bellow as a racist and a woman-hater, among other things, and accelerated Bellow’s fall from literary grace.

You can feel the lines being drawn and the gloves going up as you read Leader’s book. Leader very deliberately presents Bellow’s life in a way meant to rebut charges of Bellow’s racism and misogyny one by one. And where Atlas meanly dwells on Bellow’s minor failures — a short-lived literary magazine, several unsuccessful plays — Leader rightly celebrates his triumphs. Where Atlas resentfully interprets Bellow’s characters as reflections of their author’s narcissism, Leader gratifyingly shows how Bellow transformed his personal limitations into liberating art.

Atlas, however, will have his defenders. Some courageous (Wylie has long tentacles) people may justifiably object that under Wylie’s guidance, Leader has gone too far in the opposite, sanitizing direction, disingenuously hinting at Bellow’s dark side only to suppress it. Wylie’s author’s shrewdest move is to make the long affair that one of Bellow’s closest friends had with Bellow’s second wife, right under Bellow’s unsuspecting nose, the book’s climax. No doubt the hope is that such an injury to Bellow might help explain his misogyny and at least provide a context for Bellow’s own philandering.

You’d have to return to the 19th century, to the feverish debate over Ibsen and his plays, say, to find another author who incited such powerful, intimate responses in people. But, then, you would have to travel back at least a century to find another author who created such an entrancing promise of self-creation and liberation for his readers, only to withdraw once the wall between author and reader had been breached and you encountered the difficult man, with his sharply contradictory nature. I should know. Without Bellow’s fiction, I would not have survived my younger life.

If you think I’m exaggerating the influence Bellow had on me, consider this. A few years ago, I was on the phone with Adam Bellow, Saul’s second son — he had three sons and one daughter, by four different wives — who was the editor of a book I was writing. I made an observation about something, and Adam fell silent. “That is something my father would have said,” he told me, his voice low with emotion. As we continued to talk, it gradually dawned on me, through some involuntary process of retrieval, that in fact, it was something his father had said, something that had been embedded in my consciousness for decades since I read it, and that I had assimilated as my own.

Bellow first came into my life when I was 17 and my brother’s babysitter, a Ph.D. student in history at Columbia University, gave me a copy of Herzog. Her name was Maxine Bookstaber. Gifted with some type of empathetic clairvoyance, she must have taken pity on me. The sheriff had come to our small suburban house, pushing his way past me into our living room, to serve my deeply indebted father some writ or other. My father soon declared bankruptcy, and my mother promptly began divorce proceedings. I was a mess. Herzog, Maxine seemed to think, might console me, perhaps even supply me with a direction in life.

Not only did Herzog console me and set me on a certain path, but it offered me a way to escape my situation and to justify myself instead of pitying or disliking myself. I disappeared headlong into Bellow’s sixth novel, about a middle-aged academic suffering a nervous breakdown who writes letters to the famous dead and living taking up fundamental questions of existence — the first of Bellow’s novels to become an international success.

One passage in particular seemed to well up out of me, not Bellow. Herzog’s father, a bootlegger, arrives back home after being beaten by men who have hijacked his truck: “He began to cry, and the children standing about him all cried. It was more than I could bear that anyone should lay violent hands on him — a father, a sacred being, a king. Yes, he was a king to us. My heart was suffocated by this horror. I thought I would die of it. Whom did I ever love as I loved them?”

After losing his job in real estate, my father, owing a small fortune to his former employer, came home, sat at our kitchen table where we ate dinner, bent his head into his hands, and cried. My mother, my younger brother, and I cried, too. Like Bellow, I was Russian Jewish on both sides; open and strenuous emoting was our native language. In one stroke, Bellow validated my experience, made me feel less alone, and gave me a new family and a new idiom that I could use like a lever to rise above my life.

In Herzog, especially, Bellow seemed to create the world as he described it. That is how, in the eyes of a young child, a father speaks. Every one of Bellow’s sentences rang out with command, authority, finality. Feeling, thought, culture, history — all of it was compressed into every sentence: “The Dictator must have living crowds and also a crowd of corpses. The vision of mankind as a lot of cannibals, running in packs, gibbering, bewailing its own murders, pressing out the living world as dead excrement.”

Evoking history’s atrocities, Bellow could make you feel that you had mastered their disorder by the sheer power of thought, as he obviously had. I poured Bellow’s extraterrestrial confidence and self-assurance into my insecurities like water onto a parched lawn.

I came to love Bellow’s short story “Mosby’s Memoirs,” first published in The New Yorker in 1968, at the height of the counterculture, because it seemed to pit the Wasp mandarin intellectual Willis Mosby against a strenuously emoting, life-loving Jewish schlemiel named Hymen Lustgarten. Mosby, counselor to presidents, friend of prime ministers, deals unforgiving judgments out of a mocking, power-loving vanity. Lustgarten stands for spontaneity and heart — and Lustgarten seems to win. But I also was made rapt by Bellow’s tone in his creation of Mosby. It was godlike in its mastery of the intellectual sources of power and of the worldly origins of ideas:

The French cannot identify originality in foreigners. That is the curse of an old civilization. It is a heavier planet. Its best minds must double their horsepower to overcome the gravitational field of tradition. Only a few will ever fly. To fly away from Descartes. To fly away from the political anachronisms of left, center, and right persisting since 1789. Mosby found these French exceedingly banal. These French found him lean and tight.

Bellow, born in hard circumstances to Russian-Jewish immigrants, once wrote that “the commonest teaching of the civilized world in our time can be stated simply: ‘Tell me where you come from and I will tell you what you are’ … I couldn’t say why I would not allow myself to become the product of an environment.” I cried Russian Jewish tears of gratitude when I read that. I “came from nowhere,” as a Columbia professor of American literature once informed me. So did Saul, who was educated in public schools and at private and public midwestern universities, and who struggled to make a living until well into middle age.

Bellow’s hard-won defiance must be why even a young black man like Brent Staples, or Stanley Crouch, an older, distinguished black intellectual who became Bellow’s friend, felt such an intense attachment to him. It’s why they could feel that attachment despite Bellow’s reference to “sexual niggerhood” in Mr. Sammler’s Planet, his enraged screed against the ’60s counterculture. The phrase is repulsive, unforgivable, and inexcusable. Crouch forgave him.

You plagues on my youthful self-confidence, with your composure learned in some baronial Upper East Side or Park Slope townhouse of a home, all that reticence and discretion polished at Collegiate or Andover and then weaponized, as it were, at Harvard or Yale — you couldn’t hold a candle to me and Saul. Are you familiar with Simmel on money, Sombart on the three stages of capitalism, Weber on bureaucracy and the managerial class? I didn’t think so. Do you know what it’s like to inhabit a free, unconstrained, uninhibited space where you can yell, scream, groan, and cry whenever you feel like it? Bellow gave me a soft, lush, antique, expensive velvet pillow — think Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus; you don’t know that? You live in a $2 million Park Slope brownstone, and you don’t know that painting? — that I could place under the brick-size chip on my shoulder.

Pretty dismal and self-defeating, I admit, but it was the best I could come up with at the time. It worked for a while. Imbibing Bellow’s masterful, all-embracing applications of Western intellectual history to mundane situations mentally vaulted me over the social arrangements that stood in my way. After high school, my father’s bankruptcy, and my parents’ divorce, I wandered from one temporary situation to another: from the small, private midwestern university I had to drop out of when my mother refused to contribute to the tuition, to the state college to which I transferred, to the School of General Studies at Columbia; the whole time going from job to job to support myself.

Lacking stable situations out of which might have grown stable social relationships that I could have called upon to advance myself, I whirled around like a wrestler looking for an opening, searching for a way into the world. Up against, especially at Columbia, rich and privileged people, I tended to falter, to doubt myself. Reading, understanding, and trying to intellectually emulate Bellow gave me a special pedigree.

In this respect, discovering The Adventures of Augie March for me was like Buddha freeing himself from the oppressive cycles of life, death, and rebirth as he sat under the Bodhi tree. Augie going from one job to another, from one situation to another, mirrored my progress — or lack thereof — in the world. I wasn’t a writer; I wasn’t anyone. I told myself I was a sensitive observer of and thinker about the world, whose destiny it was to live more meaningfully than other people who, in my hampered vision, were wasting their lives building careers, making money, and having families. Augie wasn’t a writer, either. He wants to make living his vocation. His famous speech about axial lines made my heart flutter. He tells a friend that he seeks “the axial lines of life … When striving stops, they are there as a gift. I was lying on the couch here before and they suddenly went quivering straight through me. Truth, love, peace, bounty, usefulness, harmony!”

I spent a lot of time lying on the couch, let me tell you, out of despair, nevertheless convinced that I was quivering with truth and all the rest of it on my way to those axial lines. On the other hand, when I was fired from a department store in Peoria, Illinois, where I was working as a clothing salesman, for not chasing a shoplifter as he made his escape after I was commanded to do so (I wished him Godspeed), or nearly pushed down an elevator shaft in the medical-book warehouse in Chicago where I worked one summer, when I refused to be bullied into joining a union (I hated bullies, period) — these were the moments when Augie March became less a novel than a living companion.

James Wood, a passionate and brilliant reader of Bellow, set my teeth on edge. We were both at The New Republic, and when he started to write about Bellow, I felt as though someone was trying to woo the great love of my life away from me. How dare this Eton — Eton! — and Cambridge-educated Brit appropriate my beloved Bellow, the sworn enemy of environmentally conferred privilege.

Wood had an uncanny grasp of the multivalent effects of Bellow’s language. I thought that his deficiency lay in what I considered to be his inability to comprehend Bellow’s social context. He was unsuited, I told myself, to defying the-tell-me-where-you-come-from-and-I’ll-tell-you-who-you-are factor that was so close to my class-sensitive heart. I gleefully reduced him to where he came from.

It just so happened that Wood and I both reviewed Atlas’s biography, which appeared to a polarized reception, some critics praising Atlas’s decade-long immersion in his subject’s life, others crying foul at the rancor that obviously animated so many of his judgments. The division of opinion was like some tortured attempt to arrive at a consensus about Bellow’s literary worth. The biography was no less a reckoning for me. Although Wood shared my contempt for Atlas’s book, Wood’s characterization of Augie March’s William Einhorn, a rich Chicago businessman with an autodidact’s reverence for culture, defined for me the difference between our two Bellows.

I had always considered Einhorn, along with Augie himself, Bellow’s symbol of the self-made democratic man, who created himself from scratch, in defiance of his environment. (Defying environment; that was key.) The fact that Einhorn was paralyzed — like FDR, whom the young Bellow admired — was significant, I thought. But the most important thing was the way that Einhorn used culture to elevate himself above his given circumstances. That’s exactly what Saul and I had done. Wood, on the other hand, viewed Einhorn as “foolishly, ambitiously ‘intellectual.’ ” I couldn’t have disagreed more. “A sack of craving guts … what a piece of work is man,” says Einhorn, “and the firmament frotted with gold — but the whole gescheft [business] bores him.” Far from being pretentious, Einhorn spoke with the accidental eloquence that Bellow created for Augie, who calls Einhorn, without irony, “the first superior man I knew.”

After my review appeared in Harper’s Magazine, Wood and I spent, as I recall, at least one afternoon exchanging heated e-mails about what Bellow really meant to say through Einhorn. I don’t know if, at the time, what I was really arguing about was clear to me; I don’t know if Wood saw through the rhetoric to the personal issues at stake. What I remember is that we were like the only two inhabitants of postapocalypse Planet Bellow, representing two different civilizations, each striving to make his interpretation of Bellow prevail.

Despite my ardor, however, even I had begun to cool toward Bellow’s work, though I did not express that in my Atlas review. Bellow’s animus against contemporary people began to grate on me. In the 1989 novella “A Theft,” the strangely Bellow-like protagonist, Clara Velde, thinks to herself that what distinguishes America now is “essential parts of people getting mislaid or crowded out.” Bellow’s late work was full of spiteful rabbit-punches at the life around him.

But it was especially Bellow’s punitive depictions of women that turned me off. His heroes are always self-pitying in their romantic relationships, while the women are either heartless harridans or sweet, inadequate props. In fact, as Leader almost reluctantly records, Bellow could not stop fucking every woman he encountered who was a sexual possibility. More power to him, and mazel tov (Bellow’s sexual appetite seemed to infuriate Atlas), but he fucked his way through four marriages, all the while railing, with high intellectual style and moral passion, against sexual decadence.

What I had not understood about Bellow was beginning to dawn on me, just as, six years earlier, at the time of Staples’s and Kazin’s essays, it had struck everyone else. The serious Willis Mosby was more than a surprising foil for the comical Lustgarten. Bellow had spent his entire life slowly turning himself into Mosby and divesting himself of his Lustgarten side. As his Lustgarten self clowned around in bed, suffered through divorces, anguished over the painful paternal situations he had created with three sons by three different wives, Bellow became more and more the voice of offended principle and lacerating moral outrage.

By the time I finally met Bellow, in 1999, he had acquired Wylie and accrued an impressive train of admirers. Some of the most influential were British. It was only natural that, having been loudly denounced for his racist language and political insensitivity in this country, Bellow would turn to the Brits, who loved him madly. The atmosphere around Bellow, the creator of Augie March, that quintessential democratic personality, had grown incongruously plummy, clubby, and genteel.

Still, and for all that, when Stanley Crouch told me he was friends with Bellow, I asked him to ask Bellow if Stanley could bring me along sometime on one of his trips to Boston, where Bellow was living. Stanley generously did. We took the shuttle up from La Guardia one cold gray late-autumn morning. Bellow was there with his fifth wife, Janis, in front of his house to welcome us as we emerged from the taxi.

The minute I saw him, I was 17 years old once more. Bellow’s clairvoyant, transfiguring language flowed back into my veins. For all his spleen, I began to recall the clemency in his preternatural lucidity. He saw the world the way the ancient Greeks must have seen the world: glistening with the postnatal dew of burgeoning consciousness, shimmering with fresh knowledge of first and last things. I was in love again.

Bellow welcomed me graciously and received Stanley with great warmth. He led us inside the small but charming house and into the kitchen. He and Janis had laid out a large piece of lox on a platter. Bellow sliced through a lemon. Holding half of it in one hand, he drove a wooden lemon-squeezer into it with the other. He drove it in again and again; he had rolled up his sleeve and lemon juice was trickling down his arm. He continued to thrust the lemon-squeezer into the lemon, all the while looking at me and smiling. “This is how we do it here,” he said. Janis had backed up against the wall. She was blushing. Though 84, Bellow was still the alpha male. He wanted to get that straight.

Stanley and I spent six hours with Bellow and Janis. It was a lovely, golden day. But there were two moments when I saw that other side of Bellow, the Mosby side, for the first alarming time in the flesh. Bellow had become famously, or notoriously, right-wing in his politics. Yet I had always considered his politics a metaphysical protest against democracy’s secret disdain for figures of artistic or intellectual genius, like Bellow, and not a political position per se. Misinterpreting his playfulness with me as a type of intimacy, I said to him “You’re really an old-fashioned liberal. Like Mill.” His face turned black; I had never seen anything like it. He stared off into space and ignored me.

Too immersed in Bellow’s presence to register his mood, I pushed on and ventured another insight into his work. Linking Mill to what I regarded as Bellow’s scorn for money culture, I told him that I always loved that moment in Seize the Day when Tommy Wilhelm, having invested the last of his meager savings in rye, stands on the floor of Chicago’s futures market and watches his money disappear as rye falls and falls. “You were obviously,” I said, “mocking Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. You displaced his innocent Holden with your innocent Tommy and discredited the whole idea of innocence.” I was very pleased with that. Bellow’s face, incredibly, darkened another two shades, and he turned on me. “I never had anything like that remotely in mind,” he snapped with a withering glare. I uncomfortably recalled that line from “A Theft.” He shut me out for a while.

Still, though the scales might have finished dropping from my eyes, the rest of the afternoon was like some happy myth. As I walked beside Bellow to the front door, on our way out, I put my arm around his shoulders and said, “You are my real father.” It was, to borrow a phrase from Bellow, the consummation of my heart’s desire, which was decades in the making. Bellow laughed softly and flushed red. We spoke once more, on the phone a year and a half later, shortly after my Atlas review — a radiant homage to him — appeared. Bellow was warm and kind, and he urged me to visit him again. I never did. I told myself I could never be as close to him in a personal way as I had become in my imagination.

Several months after his death in April 2005, at the age of 89, I attended his memorial service, which was held at the 92nd Street Y. Wylie had organized it himself. He clearly wanted to use the occasion to rehabilitate Bellow and bring him back to the center of the American literary pantheon — not to mention selling off that backlist. But there was a coldness and emptiness to the occasion. None of Bellow’s sons spoke. Bellow’s oldest friends, some of whom were still alive, did not appear onstage. No Stanley Crouch, whose friendship Bellow had cherished. Some of the prominent authors Wylie had invited to speak had either never met Bellow or barely knew him.

That afternoon, I found myself sitting next to a predictably drunk Christopher Hitchens, who whispered to me, “I should be up there,” despite the fact that when Martin Amis had introduced him to Bellow, Hitchens immediately drew Bellow into a nasty debate about Israel. Bellow loathed him. By the logic of the memorial’s sad axial lines, though, I guess Hitchens was right. He should have been up there.

Bellow was now firmly in Mosbyland. Perhaps that’s the way he would have wanted it. I was prepared to shake myself free of the thrall of the man once more, when, upon exiting the Y onto the street, I suddenly remembered these lines from Seize the Day. It is the description of a New York street, as told through Tommy Wilhelm’s eyes by that all-knowing narrator Bellow liked to employ, whose voice resembles that of God:

And the great crowd, the inexhaustible current of millions of every race and kind pouring out, pressing round, of every age, of every genius, possessors of every human secret, antique and future, in every face the refinement of one particular motive or essence — I labor, I spend, I strive, I design, I love, I cling, I uphold, I give way, I envy, I long, I scorn, I die, I hide, I want.

My father had died a few years before, without my being aware of it until over a year after he died. That is a long, sad, different story. Something caught in my throat as I stood there thinking of Bellow and my father. I had loved many people, but whom did I ever love in the same way that I loved them? Yet I fled from both of them. I wished — almost — that Bellow was there to tell me why.

*This article appears in the March 23, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.