In a theater seating a few dozen on a stage crowded with spare canvases and Campbell’s Soup cans stuffed with paintbrushes, Andy Warhol, played by actor Ira Denmark in all black and a white wig, argued with Jean-Michel Basquiat, played by Calvin Levels in a slouching suit. “You kept avoiding me like I was some kind of street urchin,” Basquiat tells his idol turned mentor of his early days selling postcards in the East Village and haunting the Factory lobby.

Thus begins a depiction of their famous art-world bromance, brought to life in a recent in-progress rehearsal of Levels’s play Collaboration: Warhol & Basquiat, a dramatic reimagining of the working process between the two artists as they created a series of collaborative canvases that mashed up Warhol’s slick Pop imagery with Basquiat’s neo-expressionist brushstrokes in the mid-1980s, just as the younger artist’s notoriety was peaking and the older one’s influence was waning.

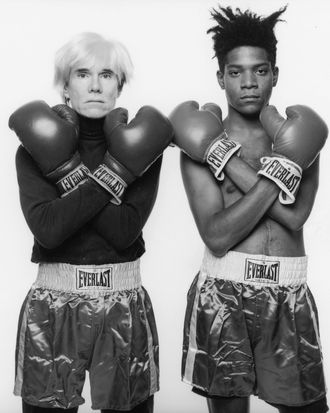

Levels’s play was inspired in part by photographs taken by Michael Halsband (who is also a producer on Collaboration) in 1985, recently on display at the National Arts Club, of Warhol and Basquiat decked out in boxing gear, throwing wan punches at each other, suggesting a certain artistic combat that was at least in part staged for the benefit of the cameras and mutual mythmaking. It’s this competitive conflict that provides the driving force of the play, which I attended a reading of recently. It explores the full arc of that decade, from unbridled creativity to crippling drug addiction, the difficulties of fame, and both artists’ eventual deaths: Warhol, in 1987, at age 58, of complications from gallbladder surgery, followed by Basquiat, in 1988, of a heroin overdose, at only 27.

“Andy fulfilled a father figure role for Jean. Jean was very bright and very childlike at the same time. He was a big kid in a way. Though he had another side, too, that people talk about, that I encountered once,” Levels tells me. (As an actor, he’s known for his role as a car jacker in Adventures in Babysitting, which came out the same year Warhol died.) It was Levels’s only face-to-face interaction with Basquiat, and he never forgot it: “When he did a show down at the Boone gallery, I went to see it. I took in the entire show, turned into a back room to see the last paintings, and Jean was standing there,” Levels says. “I said, ‘Oh, Jean, Jean, I love your work, thank you very much. I’d love to talk about doing a movie about you.’ He just coiled like a cobra, and he struck. ‘No, no, nah, I’m not interested.’ It was this side of him, that he could just eviscerate you. He did it to almost everyone at some point, even Andy.”

The actor came to Basquiat as a subject after a previous solo theater piece about the writer James Baldwin. He had written a screenplay of the painter’s life, but the project didn’t get off the ground. “I gave it to Miramax, and the next thing I knew they were doing the film without me. I kind of wish I had gone after them,” Levels said, referring to the 1996 Julian Schnabel film Basquiat. “I just didn’t think it was gritty enough. It didn’t seem to be handled in a loving way.”

In the play, Basquiat complains of “being called primitive, a monkey boy,” and argues with Warhol about the shadow cast by his own notoriety. “The state of art, Jean, is business,” Denmark’s ebullient Warhol tells Basquiat, while he frets over the younger artist’s drug use and wasted potential. After hints at Basquiat’s early homosexual experiences, the relationship verges on openly erotic, particularly during a hilarious extended monologue of a threesome Levels delivers with relish.

Physical romance between Basquiat and Warhol has long been rumored. (“It was like some crazy art-world marriage and they were the odd couple,” longtime Warhol assistant Victor Bockris wrote in Warhol: A Biography.) Levels’s play seems to assume that something happened — though no action happens onstage.

The end of Collaboration is unremittingly dark. The exhibition of collaborative canvases at Shafrazi Gallery is panned and Basquiat decamps for Europe, frustrated with his career and increasingly tangled up in his drug addiction. But the play’s depiction of its two characters is nothing if not loving. Basquiat’s relentless energy inspires the older artist, who despaired of his work, though his place in history seemed cemented. Warhol delivers heartfelt monologues reflecting on art, life, and fame while ensconced in an armchair stage left for the benefit of his tape recorder as well as the audience. “This story is more Andy than it is Jean,” Levels said. “Andy came in and kind of took over.”

One difficulty with drawing so heavily on recent history for a theatrical production is that the history’s aging scenesters are still present to offer suggestions or clarification. During a feedback session after the rehearsal, viewers didn’t so much point out corrections as offer their own versions of events. “The whole time I took Basquiat to Europe, he complained. We shared a room together at the Ritz that trip,” explained one audience member of the artist’s untimely vacation depicted in the play after the rehearsal had ended. Then again, he offered, “It’s easy to be a critic.”

Michael Halsband, who shared a similar intimacy with both artists, argued that the play shouldn’t be seen as documentary. “I had to let go of what I know as the true relationship between these two artists. The story is just a catalyst,” Halsband said from his seat in a corner of the theater. Besides, few viewers would be able to make the comparison with reality. “It’s a small audience who will appreciate that detail,” he added. Which is precisely what makes it art.