For almost eight years now, I have been a proud citizen of a world where Mad Men is the absolute most important show on television. That world uneasily coexists with the real one, where Mad Men is an elegant little bonbon that everyone talked about in 2008. The twist is, we were the “everyone” talking about it then, and we are the ones still talking about it now. We are, God forgive me, the media elite.

Sure, The Wire and The Sopranos became our new Tolstoy and Game of Thrones our new foul-tempered Tolkien, Breaking Bad had almost obviated the need for Tarantino, and we all remember that year when we thought Homeland was a masterpiece — but it was in Mad Men that the chattering classes found the only show that seemed to speak to them directly (that includes us). That’s why so many of its reviewers begged for less family drama (i.e., things any viewer could relate to) and more boardroom pitches, crazy clients, expensed dinners, and jokes about McCann (things we could relate to). Let’s admit it: Mad Men was our house soap-opera.

How does one measure the impact of a show whose most fervent fans are the people paid to talk about it? Along its way, Mad Men has hit all markers of full Zeitgeist penetration. It earned a (typically unfunny) SNL parody; The Simpsons did an episode-length riff on it (in 2011, when such things were already a bit passé); President Obama name-checked it in a State of the Union speech (“It is time to do away with workplace policies that belong in a Mad Men episode,” he said addressing the equal-pay issue). Banana Republic and Brooks Brothers rolled out clothes inspired by the series; CB2 marketed the “Draper Sofa” (best not imagine the tincture of booze and bodily fluids that would be soaking one). But the ratings show that most of these jokes, allusions, and products were aimed at a population that has never seen the show itself.

The first half of Mad Men’s seventh season averaged 3.7 million viewers, once seven-day DVR ratings were factored in, while the penultimate episode earned 3.1 million (with three days of DVR accounted for so far), making it the second-most-watched scripted show on cable that night, behind Game of Thrones. Of course, an untold number of us also watch it in an untold number of ways (TiVoed, on DVD, downloaded from iTunes, streamed on Netflix, and outright stolen). Still, Mad Men’s audience has declined in the last few years, and its numbers relative to most broadcast shows has always been small. They pale next to cable’s biggest hits — Game of Thrones, American Horror Story, the recently expired Sons of Anarchy, and The Walking Dead. Yet I’m not seeing a line of Brooks Brothers zombie suits. The media has always ignored ratings for the things it loves (otherwise there’d be nothing but NCIS and Criminal Minds stories), but this inclination reaches a new level of snobbiness with Mad Men.

When Mad Men premiered, in July 2007, I was a Mad man myself: the offices of New York Magazine, where I had just become a contributing editor, were still at 444 Madison Avenue — kitty-corner from the original Sterling Cooper, judging from that famously fake view from Don’s office. And when the gang moved, so did I: They to the Time-Life building, I to Soho and then, abruptly, to Moscow, to edit the Russian edition of GQ.

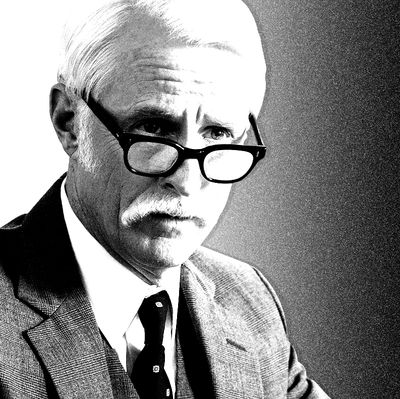

I had come to Russia with my Mad Men fandom bona fides well established. In fact, I was the show’s No. 1 proselytizer there, having once published what turned out to be Russia’s first big feature about it. Handed my own media platform, I went nuts. GQ Russia embarked on blanket coverage of Mad Men, then weirdly airing on Russia’s Kremlin-controlled Channel One. My second-ever cover subject, in May 2012, was Jon Hamm. I instituted episode recaps, a genre that barely exists in Russia. I even tried inviting Matt Weiner to Moscow to give him one of our Man of the Year awards, an offer he graciously demurred (he was busy filming You Are Here).

None of this worked. Mad Men fared much worse in Russia than it did Stateside. The Hamm issue sold like shit. The recaps, written by the magazine’s top authors, languished unread and uncommented on.

That summer, I went to a global meet-up of GQ editors in London. As I sweated into a suit among 15 or so men dressed rather like Don Draper (plus the Peggy of the group — France’s Anne Bouley), I suddenly heard our British host Duncan Jones echo my laments: “Mad Men is such an absolute brand fit for GQ. We have to write about it. We can’t not write about it. If it didn’t exist, we would have to create it. Too bad we can’t make people watch it!”

Indeed, Mad Men was tanking even more epically in the U.K. Having debuted on BBC Four, where it attracted 370,000 viewers to its season-four opener, it soon moved to Sky Atlantic, where things got truly ridiculous. The season-five premiere (the “Zou Bisou Bisou” episode!) drew 72,000 viewers. By season six, the number was 58,000. For comparison, a BBC1 documentary about the history of tea, called Victoria Wood’s Nice Cup of Tea, was watched by 3.3 million people that night.

The numbers were so defiantly awful that Slate ran a think piece titled “Why Aren’t Brits Watching Mad Men?” In Paris — where the first thing you saw upon entering the GQ France offices was a giant Mad Men poster — things were hardly better. We were fighting a losing battle.

That is, of course, if popularizing Mad Men were our true goal. In fact, I believe that by embracing it so tight we were half-consciously playing a double game: yelling “you must watch this” while claiming it as ours and ours only. Game of Thrones is a party; Mad Men was a club. Sometimes, it was even the PEN Club. When I interviewed Paul Auster, in 2010, he seemed equally disgusted by all modern pop culture until I mentioned Mad Men: “It’s not bad, huh?” he smiled. That “huh” was key. Mad Men was the show that guys like Paul Auster deigned to watch, and others watched to meet them halfway. It wasn’t about writers; it was about what writers wanted. No matter how many lightning bolts of tragedy and betrayal Weiner leveled at his characters, the series’ aspirational underpinnings never came loose. Don’t believe me? Go ahead and check who among us still uses cartoon avatars from the “Mad Men Yourself” app.

And that’s fine. We’ve had our own little thing, our precious premium product, and now we must say our premium good-byes to it, all over the media. As for the rest of the world, it will shock you how much Mad Men never happened.