The tagline for Tiller Russell’s riveting new documentary, The Seven Five is “Meet the dirtiest cop in NYC history,” which I suspect does a profound disservice to a lot of other NYC policemen, past and present — although none of them are likely to write letters of complaint. Some cops (not the majority, who risk more every day than most of us will in a lifetime, but some) might watch this film with a peculiar mixture of shame and pride. Michael Dowd — who survived and thrived in the ‘80s in East New York, “the land of fuck” that “would scare Clint Eastwood” — had big balls and didn’t rat out fellow officers. He was dirty, but the 75th Precinct was, after all, a shithole.

This was the height of the crack-cocaine epidemic, when so much money moved through a “ghetto” like East New York that cops would call it “one of the richest neighborhoods in the city.” New recruits would wonder what they’d done to get assigned to the Seven Five. Even now, they show little sympathy for the people who had to live there. They think of it as a war zone and everyone as a potential enemy combatant.

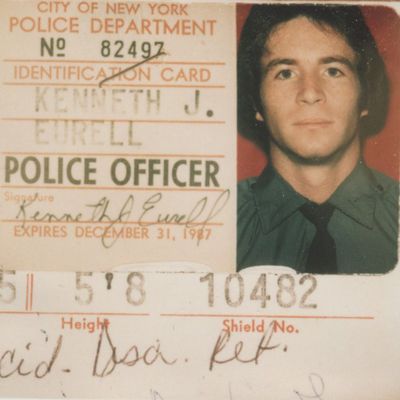

A young officer named Ken Eurell tells Russell he learned of “Mikey D” before he met the legend. He heard that Dowd was a “criminal in a cop uniform” and routinely ripped off drug dealers using police techniques. Then, suddenly, he was Dowd’s partner, his newfound bounty compensating for the high risk and meager pay. Eurell had a family, a mortgage, and kids; for a while, he could tell himself he was in that world but not of it. The Porsches and Jaguars were fringe benefits. His and Dowd’s families socialized. On the street, they had each other’s back.

A man named Diaz — cloaked in darkness — spells out Dowd’s alliance with the most murderous gang, the Dominican “La Compania,” for which the cop did his dirtiest work. I’m amazed Russell had access to Diaz at all. And I’m amazed he got Dowd to talk so freely. (It’s true that Dowd has little left to hide: The film opens with footage of him before a 1993 commission admitting to thieving, extortion, and heavy drug use.) I’m probably not alone in finding Mikey D immensely likable. He has served his time and his conscience seems clear. Compared to Eurell, he is supremely centered. But that’s easy to understand. It was Eurell who broke and gave evidence.

By the definitions I’ve read (most recently in The Psychopath Test by Jon Ronson and Murderous Minds: Exploring the Psychopathic Brain by Dean Haycock), Mikey D is a psychopath: fearless of consequences, devoid of empathy, and capable of great charm. And Ken Eurell deserves some kind of medal for getting a badge out of Dowd’s pocket and a gun out of his hands.

But I suspect that’s not director Russell’s view. On some level, he reveres the bonds among outlaws and has a romantic sense of loyalty, and he can’t resist adding an end title about Eurell that suggests his contempt. It’s an ugly touch, reminiscent of a lot of writers and directors who fall in love with cops and reserve their deepest disdain for “rats” or Internal Affairs officers.

I think people like Russell add to the toxicity, thickening the wall that separates cops from the citizens they’re tasked to protect. But maybe we need someone as plainly amoral to make a documentary as good as The Seven Five — someone more interested in the effect of tribalism than in sermonizing, someone who can get men like Dowd and Diaz to open up. I don’t respect Russell, but in this case, at least, I’m grateful for the inside view.