Last week, the Whitney museum opened its new building to the public with the exhibition “America Is Hard to See,” spanning several floors and drawn entirely from the museum’s permanent collection. Because that collection is what it is, the emphasis was on work from the first half of the 20th century — art from the modern period that isn’t exactly “modernist,” American painting before Abstract Expressionism and Pop really put America on the global art map. Here, senior art critic Jerry Saltz talks with editor David Wallace-Wells about what exactly can be seen in the revelatory show.

David Wallace-Wells: Jerry, walking through the Whitney last week with you was a blast. But I also had a weird feeling — a sort of déjà-vu-y feeling. This may sound kind of insane, but for a while, I’ve been secretly wondering whether modernism ever even really took place in America. Mostly I was thinking about books — self-conscious avant-gardists like Joyce, Woolf, or Mann, these people were just up to something different than the American undergraduate mascots (Hemingway, Fitzgerald). There’s something similar in music, I think, even though I know basically nothing about it — we had jazz, a sort of refined parochial, vernacular music, but nothing like what cosmopolitan radicals Stravinsky or Prokofiev were up to. Looking at all the pre–World War II work in the Whitney’s inaugural, from-the-permanent-collection show, a sort of showcase of the best and biggest hits of American art, I had the same feeling. I thought, Wait, this isn’t modernism, it’s folk art! Or folk art on an imperial stage, anyway. Am I crazy?

Jerry Saltz: I’d say you’re crazy like a fox and really onto something. The real revelation in “America Is Hard to See” comes in the works from before World War II — how not-European, not-modernism modern, not-programmatic, not-pure it looks. How weird. And for my money, wonderful. I’d bet that most people have no idea about this history, or if they do know it, that these facts have never quite been laid out to reveal this as blatantly.

DWW: Wait, so what “facts” do you see?

JS: At the same moment in the early 20th century when Europe and Russia, especially, were trying to make art dealing with the modern condition, Americans were actually just being modern, living it. It would have been silly for Americans to make Malevich’s all-black painting. While our European counterparts were going on about artistic ideas like “the zero of form,” calling for the destruction of museums, and Duchamp was pronouncing that “painting is over,” Americans were like, Huh?! They were craving kids late to the party, eager to rush in where only fools would go. American artists knew about and were using, duplicating, and learning from European modernists, but American artists were trying to do something impossible — which is how they ended up succeeding: They were trying to be modern without Cubism, Fauvism, and Futurism. Without the creeds of those things. That’s also what explains the look of “folk art” that you mention, all the off-the-wall eccentricity in the early sections, artists toying around with abstraction and grids and all that serious stuff but then always being unable to refrain from sticking in a bridge, a building, a billboard, or subway trestles. I mean, when Mondrian got here, he painted his most eccentric masterpiece — Broadway Boogie Woogie. This has never been as clear as it is right now at the Whitney. And it’s thrilling.

DWW: But let’s back up for a second. What do you think explains that, um, provinciality? If they knew about it, why weren’t American artists of that time excited by Cubism or Fauvism, say, in the same way the Europeans were? Your sense that Americans were too busy being actually modern to deal artistically with modernism is fascinating to me, but some of this has to do with simple distance, right? And the difficulty of transporting artistic movements across oceans (easier, actually, when you’re shipping reproducible books rather than singular and very expensive paintings …).

JS: We may once have been thought of as and believed we were “provincial.” The shock of this show — and I think it’s only the first of many shocks in store on these floors of the museum — is how we can finally see that American art was “modern” all along, not in the ways the Europeans had conceived it, but in new ways — not in schools, -isms, and ideologies, but with its own clunkiness, obsessions, eccentricities, subject matters, and ideas of color, surface, composition, and skill. Virtually every American artist was aware of what was going on in Europe; each knew that to be a contemporary artist meant to incorporate European art. Many American artists went there and were transformed.

DWW: So why does all the work from that period look so different?

JS: It’s just that once this transformation took form back home and instantly spread in every direction, that Cubism, Dada, Futurism, Fauvism, Expressionism, and all the rest came out differently, more mystical, pragmatic, haunted, and formed by a lack of living models to build on, no history, museums, schools, or scads of artists. American modernism had to be made up, based on instinct, will, desperation not to be left behind again, ambition to equal and add to what modern was. This didn’t stop the press and public outrage. The New York Times wrote, “Cubism and Futurism are making insanity pay.” Modernist art was seen as “epileptic,” its artists “paranoiacs,” “degenerates,” and “dangerous.”

When I say we were “too busy being modern,” I mean that there wasn’t any society, structure, or aesthetics for American artists to build on, undermine, destroy, or distance themselves from. Tradition-wise, except for past masters, Hudson River painting, society artists, visionaries like Homer, Ryder, and Louis Eilshemius (who’s sadly absent at the Whitney), and expats like Cassatt and Whistler, art itself was pretty much terra incognito. Americans just hadn’t ever really done it before.

DWW: So American artists had a sort of blank slate. Or a blank check.

JS: American artists really had to go it alone, and this may have driven them deeper into these eccentricities. Anyway, when Europeans pictured the modern world, it looked like America. What Europe looked like to us was a blast of an act we didn’t just want to follow but get in on. We were baby chicks imprinting on everything, piling in the water every which way at once. As usual, Picasso was first to see that Americans were new types of beings. Of those he saw at Gertrude Stein’s Rue de Fleurus salon, he said, “They are not men. They are not women. They are Americans.”

DWW: I wanted to ask you about some particular works, too. I loved seeing Marsden Hartley’s Madawaska, Acadian Light-Heavy, Third Arrangement. I’m art ignorant, I know, but it reminded me a lot of one of Picasso’s self-portraits, from 1906. (For some reason, the JPEG version that’s lodged in my memory has a more similar color palette; amazing how that can happen.) But the Hartley was painted in 1940! Light-years later. Elsewhere in the Whitney, there were also glimmers of Americans trying on Cubism (Patrick Henry Bruce, Stuart Davis), Surrealism (Louis Guglielmi’s Terror in Brooklyn, from 1941), other -isms. But in so many cases, those glimmers came years or even decades later than the European ones, and somehow seem not just late but … lacking, imitations more than anything else. Why were Americans having so much trouble with this stuff?

JS: That Picasso self-portrait is a killer — holding a painter’s palette and looking into the distance of history like some new, super-masculine magician of the earth. So is Hartley’s equally reduced, amazingly archaic, flattened picture, although his figure is more physically assertive and very much of-the-flesh, looking at us with something like the pathos of older Roman sculptures of wrestlers; the moist, matted hair on the Hartley chest, the six-pack abs, and maybe the most erotic male nipples ever painted, not to mention the sense that Hartley was in love with this body, not his own, not Picasso’s, but the subject’s. This lets us see Hartley, a first adapter to European modernism, combining Cubism, Expressionism, and Picasso’s early reduced Iberian style, and adding ideas of spectacle, prizefighting, posters, and the mysteries of desire into the mix. It’s hard to compare anything to that tree-shaking Picasso, but if anything can stand up to it in terms of will and visual assertiveness, it’s this incredible picture. I think I might even take it over the Picasso. And the crimson reds are as raw as any in the museum.

Elsewhere, you can see what happens when Americans do get too close to just formal styles — say, Cubism. Max Weber’s picture is large, lovely, and ambitious, but it doesn’t deviate from or add to European DNA; it fizzles on the wall as just another early adapter who flew too close to the Cubist sun. E.E. Cummings’s abstract painting is a spectacular train-wreck of a thing with attractive parts that never congeal into any kind of a whole. The fabulous thing about his painting is that he made it at all — which gets back to my self-made point: Cummings might not have known about two-dimensional abstraction and color, but he went ahead and made one of the bigger paintings on that floor, anyway. That’s the “we already lost the art war, so we’ll play anyway and try to change the game” American-ness of so much of this work.

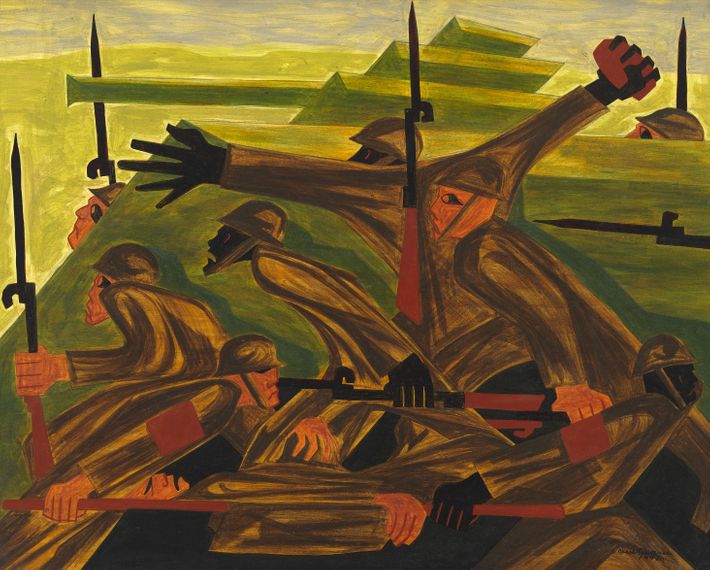

Nearby, Alice Neel and Jacob Lawrence take on Picasso, not to mention Goya, trying to paint social strife and World War II, and their paintings have their own pictorial densities, styles, ideas about suffering, and — in the case of Lawrence — being a black American solider. It doesn’t matter that both of them couldn’t have happened without modernism; they both make modernism sing new songs. Great ones. De Kooning does the same thing, only more, and with some of the sexiest paint seen since Titian. (His Door to the River is the most loamy, ferocious thing in the museum.) Of course, de Kooning was Dutch. But as an illegal immigrant who got here as a stowaway, that counts as American. I mean, I’m the son of an illegal alien! Which I guess makes me an anchor art critic?

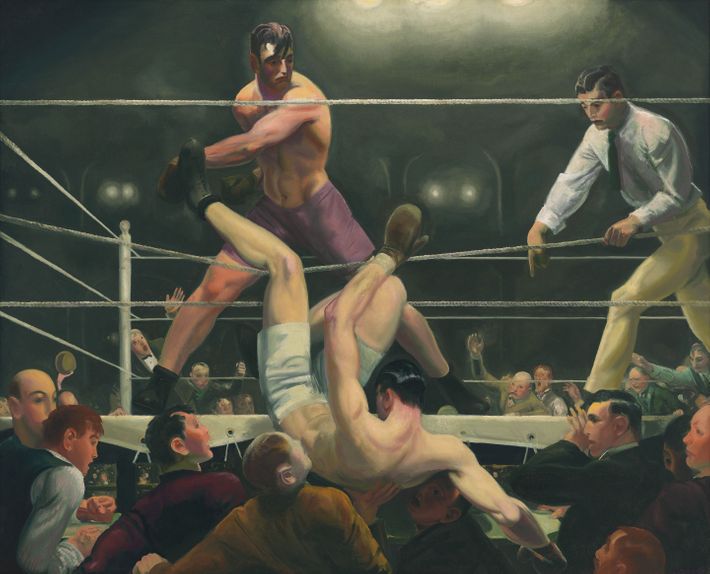

DWW: Can we talk about some works that feel even less connected to the European tradition? On the fifth floor of the Whitney are Ralston Crawford, Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, Elsie Driggs — these are works about industrialization that look to me like children’s-book illustrations. Okay, yes, incredible children’s-book illustrations, but still so dreamily naïve and Romantic. Then there are George Bellows’s boxing scenes (for starters …). That Joseph Stella bridge! The Europeans of this era were Romantic in their way, too — but it seems to me mostly about art and artists. The real king painters of the interwar era in America — guys like Thomas Hart Benton, Bellows, Grant Wood, and John Steuart Curry — seem hopelessly romantic about the stuff they were painting — namely, America! Even when they’re gloomy, those massive, mural-like canvases seem full of folk romance, and that work struck me as almost the heart of this Whitney show, by artists who were — I think! — self-consciously resistant to Europeanism. Or am I misremembering my Art History 101?

JS: When we get to artists like Benton, Bellows, Grant Wood, Curry, and many others, we’re getting to what it meant to be modern without modernism, and to histories that we’ve viewed as stylistic skeletons in the art-historical closet. Namely, Regionalism. At the Whitney, these artists, even with the cheesy, hackneyed, sometimes-creepy storytelling, mythmaking, and softball celebration of America, shine forth. At the Whitney, we start to see that even the idea of an international style is, in a sense, artistic colonialism and capitalism having its way.

DWW: What do you mean?

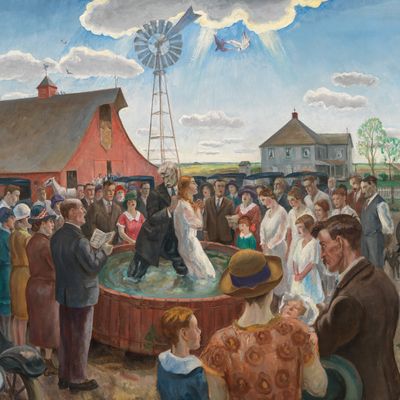

JS: Basically, that the off-center American art reminds us that specificity and individuality, not global style, are what we come to art for. It’s not artistic nationalism. That’s what I was thinking about John Steuart Curry’s Baptism in Kansas. This gripping 1928 depiction of an ashen preacher dipping a white-gowned woman in a cattle trough, surrounded by people singing and praying, dogs, and farm buildings, touches ever so lightly and troublingly on isolation, fear, faith, and the psychological darkness of the American night. William Glackens’s picture of the Hudson River hanging almost at the place he actually painted it lets us see an American artist turning Hudson River painting into almost pre–de Kooning, pre-Pollock physical expressionism. Thomas Hart Benton’s weirdly El Greco–like colored pious husband and wife at a table with an embroidery above them reading “The Lord Is My Shepherd” drives this point home while also pointing the way to some of the strident colors used by Pollock. When was the last time the belly of the regional beast looked so harrowing, driving, and relevant? The curators have dismissed the charge of yokelism. For good, let’s hope.

DWW: Is it me, or is art of this era, and this kind, having a moment? I don’t mean just that the Whitney has reopened with a show celebrating it — I mean that for the first time since I’ve been paying attention, artists and curators and critics seem engaged and excited by it. It’s no longer the case that Duchamp seems to tower above everyone else from his era as an influence on today’s artists, I don’t think. Instead, I see people plumbing everywhere, plumbing this sort of deeper, weirder, more personal tradition, one open (possibly) to more idiosyncratic reimagining and repurposing. Do you see the same thing? If so, what do you think it’s about?

JS: I’m so into this new plumbing! Although I do think it was Duchamp who said, “The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.” This was not long after he purchased a urinal at J. L. Mott Iron Works at 118 Fifth Avenue, took it to his studio at 33 West 67th Street, turned it on its side, signed and dated it “R. Mutt, 1917,” titled it Fountain, submitted it to a non-juried avant-garde, got rejected anyway, and basically set off an artistic atom bomb. (Interestingly, the only photograph of this turning point was taken in Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery, with Fountain proudly displayed with a great early Marsden Hartley.) Your question about why these floors of the show hit home harder or more profoundly than the more recent floors has something to do with all the enervated look-alike formalist abstractions and seeing the same artists in different biennials all over the world. The Whitney knows what artists know: This old artsy international style has been all but clear-cut for new ideas and is growing sterile; at the same time, all this other odd or embarrassing or unknown stuff is coming to light and being embraced; not just from North and South America, but from styles, mediums, and aesthetics that academia never factored in. How shunned was American art? MoMA owns only two Hartleys; they almost never hang. As told by MoMA, modernism didn’t really happen in America until the 1940s, when Abstract Expressionism sorted everything out. “America Is Hard to See” puts the lie to that cliché.

DWW: It’s probably good you mention Abstract Expressionism, since it’s one hard-to-refute objection to my ridiculous grand theory. “What’s more modernist than de Kooning?” somebody just asked me, mockingly — and pretty confidently! And yes, those big, swinging dicks were certainly up to something new. But if you squint hard enough and forget their own rhetoric about the novelty of what they were up to, I think you can also see their project as a kind of quotation, almost postmodern in that way, repurposing and reinvigorating European gestural styles from much earlier in the century — Kandinsky, Malevich, etc. And anyway, they were postwar!

But let’s stick with interwar for another minute. Before I let you go, I wanted to ask about a couple of artists from that era who aren’t being rediscovered now, who’ve been with us in very big ways all along: Edward Hopper and Georgia O’Keeffe. Hopper especially is the sort of spiritual center of the Whitney, and always has been. O’Keeffe is less central to their collection, but is probably the most recognizable (and surely the most poster-ized) painter of those decades. How do they fit into this story?

JS: First I want talk about that “big, swinging dicks” thing. In truth, most of those guys were desperate, poverty-stricken alcoholics. A lot of them killed themselves. By way of never minimizing their accomplishments again, a comparison: When Picasso finished his epoch-changing Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, he invited people to his studio and asked, “Is this a good painting?” He’d altered the idea of quality, skill, color, and structure. When Pollock showed his first drip works to his wife, Lee Krasner (whose huge painting looks the best it ever has at the Whitney), he asked, “Is this a painting?” He’d actually shattered categories. That’s how radical some of these guys were. For those still calling them “big dicks”: After struggling for a lifetime, they only ruled the roost for ten years. By 1958, young artists who didn’t want to be “modern” the way these older artists were being modern cast much of it aside. Instead of big, ardent, splashy abstract paintings, they made cooler, more realistic, smaller, ironic, pop-inflected works. Almost as soon as artists like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol appeared, Ab-Ex was cast aside.

DWW: Okay, fair enough.

JS: Sorry about that; I think seeing things in -isms does a terrible disservice to art and artists, erases originality, and closes down seeing. I hate it. It’s time we wean ourselves from this thinking in -isms and decades. Back to Hopper and O’Keeffe: Many outside America still pooh-pooh them as either fine and not modern or just fine illustrators. In fact, both were more modern than people know, and as original in their ways as any supremacist, Surrealist, or mad Dada anarchist. I’ve written that “Hopper is the Whitney’s Picasso,” meaning he’s the artist people most associate with the museum, the one they come to see and whose art better always be on view, the artist the museum is deepest in. Hopper is the Leonard Cohen, Roy Orbison, and Bruce Springsteen of painting, an only-the-lonely artist of ordinary life, trying to survive, America as universally accessible. His invisible modernity is in the radical ways he redefined the conventions of good painting, modernist and traditional alike; he brought ideas of illustration to art, roughed up traditional painting while smoothing out modernism’s stuttering touch, turning his blocky composition into his own narrative versions of Mondrian and Malevich. At the Whitney, his image of an empty storefront at 7 a.m. at the end of a town street on the edge of the woods rides that thin American line between lives perused, lives lived, and lives lost along the way.

DWW: He’s also been sort of casually derided, for decades, at least, as a sentimentalist. Which does make me think that’s another way that these American painters were different, in addition to their relative disinterest in avant-garde-ishly trying out new forms and new styles. I’m simplifying in the extreme, obviously, but this work is also so much more powered by sentiment than the European stuff of the era. Why is that? I mean, simplifying again to the extreme, theirs was the civilization that was completely falling apart!

JS: Yes. Now we know what those Europeans knew, that end of empire. Hopper knew something different: the solitude of American freedom, living in this country that was on the verge of an “American century,” but with the original sin of slavery ever-present, feeling that cathedral of longing inside of us, proud to be Americans but knowing that glory and specificity is fleeting, filled with fear, something sealed off, a well of alienation. Hopper painted that. It may come off as “sentimentality” to some. At the Whitney, look closer: You see something darker, some searching, colder nights.

DWW: And then there’s O’Keeffe.

JS: I wouldn’t wish what happened to her on any artist. Even today she’s dismissed as a prissy painter of pretty pictures of vulvas, feminine folds, flowers that look like vaginas, a woman artist included when a “woman artist” is needed. Her work has been reduced to calendar art and dorm-room posters. In her own time, it wasn’t much better; male critics wrote that she painted in “great painful and ecstatic climaxes,” referred to her as “this girl,” was said to think “through the womb,” giving viewers “an outpouring of sexual juices” and “sex bulging, sex tumescent, sex deflated.” No wonder she left New York behind and lived in relative isolation in New Mexico for the last 37 years of her life. The fact is that O’Keeffe was making abstract art as early as 1915. This means that she was one of less than a dozen people on Earth at that time who were thinking of art in terms of total abstraction. It doesn’t get more radical than that. Her ideas of pale color, thin surface, larger scale, and amorphous pictorial structure presage artists as varied as Milton Avery, Mark Rothko, Morris Louis, Hedda Sterne, Mary Heilmann, and most contemporary abstraction. O’Keeffe allows us to experience the nonobjective as mystical, familiar, objective, and subjective all at once.

For me, this show not only reminds us of their radicality but has the added bonus of suggesting that much of the weight placed on these two artists can now be shifted, spread out to a lot of other artists. We’ve seen this of late with revelatory exhibitions of Charles Burchfield, Forrest Bess, and a show of early Hartley. We haven’t even mentioned what’s in store when we allow in some of the greatest visionaries of all time, Florine Stettheimer, Martín Ramírez, Henry Darger, Bill Traylor, and James Castle. I mean, Traylor was a former slave; that vision needs to be seen in museums.

DWW: That would be something.

JS: Those still clinging to claims of the inadequacies of North American art might want to throttle it back a bit and realize that they have nothing to fear.

DWW: Wait, did I say “inadequate”?

JS: Not you! And I think that the vast majority of new audiences will see all this art without the filters of dogma, too. That alone makes the new Whitney a godsend to art. As it is, the Whitney is and will probably always be the only museum in the world that gives this much real estate to American artists of the first half of the 20th century. “America Is Hard to See” made the insatiable ingrate American in me wish for more space for the art of this period.