With the release of Go Set a Watchman, by Harper Lee, fans of To Kill a Mockingbird are being forced to reconcile a new, crankier, more racist iteration of Atticus Finch with the earlier character they love so much — if, indeed, these two versions can be reconciled at all. So which Atticus is the real Atticus? For guidance, Lee readers should look to fans of comic books and science fiction and fantasy literature, for whom debating the legitimacy of various versions of the same character — not to mention scrutinizing the tiniest details in a larger fictive universe — is all part of the hallowed task of determining what counts as “canon.” And in these realms of pop culture, canon is everything.

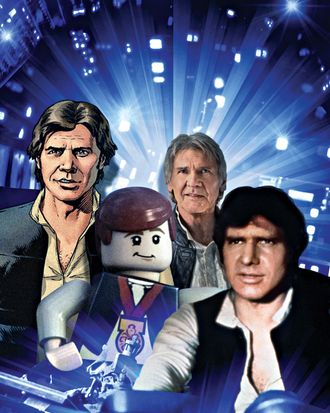

The notion of canon as an officially sanctioned body of work originated with perhaps the most high-stakes example of canon-building in human history: decisions by Roman Catholic church leaders, pre–500 A.D., as to which books of the Bible would be considered divinely inspired, or canonical, and which would be dismissed as apocrypha. Canon has, more recently, come to refer to materials that are, or aren’t, considered to be “officially” part of an expansive narrative that’s told across many media — the world of Star Wars, or The Avengers, or Game of Thrones. Canon can pertain to everything from tiny factual details (where a character was born; the design of a coat of arms) to more intangible components, such as the nature of a character’s character. “Fandom is about joy, and canon is one of the elements of the pleasure fans derive from our favorite stories,” Heather Urbanski, an academic and self-described “overall SF geek,” told me. But, she says, there are those who believe that their fandom “endows them with authority to pass judgment over what is ‘allowed’ in canon and what is not.” In a recent, fairly typical blowup, Han Solo was revealed, in a comic-book story, to be married. (Or, at least, a woman showed up who claimed to be his wife.) Fans of Star Wars might here note that Han Solo has never mentioned, nor even alluded to, nor even seemed particularly inclined toward, being married — certainly not in any of the movies that you most closely associate with Han Solo. Yet the comic book in question is considered canon. So say hello to Mrs. Solo.

The curious case of Sana Solo (that’s his ostensible wife) demonstrates why we may be facing a looming canon crisis. The J.R.R. Tolkien canon, for example, was once fairly simple to determine: It could be straightforwardly described as “books written by J.R.R. Tolkien.” For his modern equivalents, it’s much more complicated. Star Wars has birthed such a tangled lineage — movies, comic books, novels, video games, even an infamous Star Wars Holiday Special — that Lucasfilm employs a man named Leland Chee to be the official keeper of the canon. This job includes maintaining a database with more than 60,000 entries on every character, planet, weapon, vehicle, etc., ever mentioned, pictured, or described in any of the various Star Wars spinoff products. (As Chee told Wired: “Someone has to be able to say, Luke Skywalker would not have that color of lightsaber.”) The Game of Thrones canon, unbelievably, is even more convoluted. The Thrones world is now officially split into two parallel and, in a sense, competing narratives. There is the canon of the still ongoing series of novels by George R.R. Martin — which has been expanded to semi-officially encompass Martin-sanctioned information provided to leading fan sites as well as a Game of Thrones role-playing game. But that canon doesn’t include the Game of Thrones TV show, which is its own separate, parallel canon, inspired by, but not beholden to, the universe of the books.

This might all seem like needless ecclesiastical nitpicking until you consider that, in the most recent season of Game of Thrones, the two canons diverged dramatically: Characters were killed off on the show who live on in the novels and, perhaps more distressingly, other characters acted in ways on the show that seem at odds with their characters as portrayed in the novels. In a Guardian column, Spencer Ackerman pointed out that several recent events on the show are apparently inspired by things that might happen in the books but haven’t yet: For example, in the novels, Tyrion has never met a dragon but likely will; on the show, he already has. So, Ackerman asks, “if Martin doesn’t write his story the show’s way, will the original author be deviating, in a meaningful way, from canon?” Ackerman points out that Game of Thrones is no longer “just magic, war and toplessness. It’s a literary experiment, however accidental or forced by circumstance, that shatters through stale academic debates about authorial intent and semantic autonomy.” There’s now a vocal contingent of Game of Thrones fans online who believe the show has deviated so drastically from the novels that it amounts to heresy. A particular sacrilege is the episode in which Stannis Baratheon burned his daughter at the stake. In the books, his daughter still lives. You might argue that these are two different Stannises, but that raises the thorny question: Which is the true Stannis Baratheon — and who gets to decide?

This is where questions of canon rub up against questions about the nature of storytelling itself. As a fan, it’s tempting for me to reject one storyteller’s version — her Atticus versus yours — but do these characters belong to you or to their creators? Especially given that part of the joy of being told a story is putting yourself in the hands of the person who’s doing the telling. And yet if tomorrow J. K. Rowling released a novella claiming that Harry Potter was a deranged schizophrenic and all the preceding books an asylum-bound fever dream, fans might rightfully decide to ignore its existence, essentially wresting control of the characters from their creator. Perhaps canon is best seen as a kind of symbiotic process between a story’s creators and its fans — one that, ideally, results in the richest possible narrative. Some critics have suggested, for example, that the new version of Atticus Finch creates a more interesting, more expansive, if less palatable version of that character — and that this challenges us, the readers, to not simply refuse the new version but to thoughtfully reconsider the old one. For fans, it’s certainly not the easiest response, but it may be the most rewarding.

*This article appears in the July 27, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.