In the lyrical 1954 melodrama Struggle in the Valley (also called The Blazing Sky), his first starring role, Omar Sharif plays a young, college-educated peasant who finds himself warring with a local Pasha, the father of the woman he loves (played by Faten Hamama, whom the actor married). The director, Youssef Chahine, was one of Egypt’s most important filmmakers; much of his later work was acclaimed internationally, but here, it’s all florid emotions and stacked-deck injustices. Sharif ends the film wounded and shirtless, staggering out of the Temple of Karnak with his lady love (also wounded, not quite shirtless), several bodies in their wake. It’s ludicrous stuff, but also somehow deeply compelling, thanks to the chemistry of its two incalculably beautiful leads. As the romantic, earnest Ahmed, Sharif is smoldering yet reserved: He may be playing a peasant, but he has an almost aristocratic composure.

After that auspicious debut, Sharif (who was born Michel Demitri Shalhoub) became well known in the prolific Egyptian film industry, often appearing alongside Hamama, to whom he was married until 1974. (The actress, also a huge figure in Egypt, died earlier this year.) And over and over we see him taking advantage of that quiet, regal bearing: It makes it that much more effective when he finally explodes (as he usually does, these being melodramas). It also served him well in his infamous English-language debut in Lawrence of Arabia, playing Sharif Ali. The part was originally supposed to go to the great French actor Maurice Ronet. For some smaller parts, Lean had asked producer Sam Spiegel to find him “at least six real Arabs who can speak English [and] can do the odd line here and there.” As Lean told it, “He produced about twenty photographs which I went through and I was suddenly stopped short by Omar’s face. Sam said he was once quite a big Egyptian film star, but something happened and he had faded from view. ‘I like that. He looks good,’ I said.”

Lean met with Sharif and, impressed with his acting (and also having decided to put a mustache on him), had the actor try out for a couple of the smaller parts in his film before realizing that he should play Ali. Sharif’s first day on set was also his first, immortal scene with Peter O’Toole’s T.E. Lawrence — after Lean’s unforgettable introduction of Ali through a shimmering mirage. It’s an exchange worth looking at, for its economy and for the way the two actors play it: “This is my well,” Ali says, as a way of explaining why he’s shot Lawrence’s guide. “I have drunk from it,” Lawrence says, irate at the injustice of a man being shot for taking a drink of water in the middle of the desert. “You are welcome,” is Ali’s reply, and in that one moment — in Sharif’s matter-of-fact delivery — the supposed laws of the desert (completely made up, by the way, over one Lawrence biographer’s objections), and the hierarchy of who can drink from whose well, suddenly makes a strange, intuitive kind of sense. Watch how Sharif’s cool plays off against O’Toole’s broad theatricality. That’s the ineffable quality of presence, and Sharif had it in spades — more so than just about any other actor of his generation.

In part, of course, this had to do with what viewers back then would have called Sharif’s exoticism. (There’s a loaded word.) Back then, Lean had the artistic confidence to give the two biggest roles in his film to relative unknowns, Sharif and O’Toole. But giving Ali to a Middle Eastern actor — what Ridley Scott might call “a Mohammed so-and-so” — was seismic. It was a heroic part — Han Solo to Lawrence’s Luke Skywalker — and it immediately made Sharif a star. He wasn’t just nominated for the Best Supporting Actor Oscar for that year; he was tipped to win it.

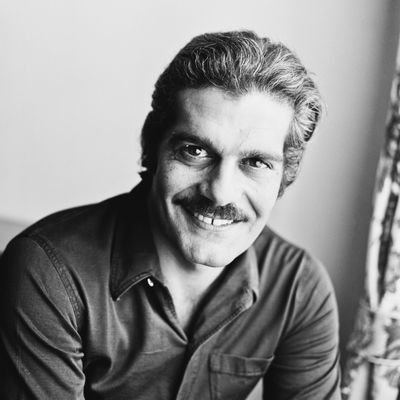

An Egyptian working in the international film industry — during the heyday of big-budget Euro-pudding productions — Sharif could always expect to be cast as an Armenian king, a Mongol conqueror, an Austrian prince, Cuban revolutionary, a Spanish priest, or Yugoslav partisan. But he could rarely just be a heavy, or a functionary. Part of it had to do with that face: perfect cheekbones; heavy, long-lashed eyes; and a kind mouth, usually framed by that thin mustache. It’s hard to imagine that face doing anybody real harm.

Following the success of Lawrence, Lean put that face and that bearing to good use when he cast Sharif as Yuri Zhivago in his adaptation of Doctor Zhivago. Interestingly, the director had initially thought of Sharif for the role of Strelnikov, the idealistic student and revolutionary turned dogged executioner played later by Tom Courtenay. The part of Zhivago — a kindly doctor, poet, and lover — had been hell to cast; the studio had wanted Paul Newman, but Lean objected, saying he could “discover nothing of the dreamer about him.” Later he considered O’Toole, but even there he wasn’t so certain. “One of the hardest things to cast is a good man,” the director said. “The more ‘good’ they are the more dull they appear when they reach the screen … Zhivagos do not become actors.” He finally realized that Sharif would be perfect after several other options fell through. It was an incredible bit of luck for both men.

Doctor Zhivago is one of those stories where good men go silent and bad men seize the day. But as Sharif plays it, that silence comes off as dignity, rather than fecklessness. He understands the injustice around him, but refuses to fight it with further injustice. And his romantic hesitancy is the inner uncertainty of a man in love with a woman who is not his wife. Watching Zhivago, it’s amazing how reactive Sharif’s performance is: So much of the film plays out through shots of his face. In the scene where Zhivago first professes his love for Lara (Julie Christie), Lean bathes Sharif in shadow, making sure that we only really see his eyes. Meanwhile, the scene where the Tsar’s dragoons mow down a peaceful protest in the street is anchored by Zhivago’s quietly anguished reaction. (“David told me to think of being in bed with a woman and making love to her,” was how Sharif later explained Lean’s direction of him in this scene.)

Zhivago sent Sharif’s star into the stratosphere and cemented his position as an international heartthrob. But unlike his fellow international hunks Marcello Mastroianni and Alain Delon, he never quite had a thriving, high-profile home film industry — no Federico Fellini or Jean-Pierre Melville of his own — he could retreat to when the Euro-pudding productions dried up or failed. His own relation to the Egyptian film industry was complicated. His films were looked down upon in the wake of his appearance in Funny Girl, romancing Barbra Streisand, a Jew, at the height of Egypt’s tensions with Israel. He returned after President Anwar Sadat personally invited him back, and later appeared in some local productions. But he remained a man of the world. “The international wog, I am,” he once glibly told an interviewer. “I speak five languages, but I don’t have a mother tongue. I don’t speak one language perfectly, or without an accent at any rate.”

Still, Sharif worked steadily, and almost always in big movies. But even he agreed that a lot of the movies he made were rather dire. Of course, some of the films he dismissed are not so bad: I know for a fact that he, along with pretty much everyone else involved, hated Alejandro Jodorowsky’s The Rainbow Thief (1990), which reunited him with O’Toole, but the film is too strange and unpredictable to dismiss. He probably didn’t think much of Francesco Rosi’s More Than a Miracle (1967), a colorfully anachronistic Neapolitan fairy tale in which he played a dashing Spanish prince (of course) who falls for Sophia Loren, but the film is actually quite magical. He doesn’t appear to have liked Juggernaut (1974), an impossibly tense terrorism thriller set on a ship (he, naturally, plays the captain). I don’t know what he thought of Top Secret! (1984), but holy hell, is he hilarious in it. (Why on Earth didn’t he make more comedies?) And he brings a fantastic sense of old-world adventure to The Thirteenth Warrior (1999).

His international stardom — not to mention his reputation as a great lover — also helped him become a huge figure in the Middle East. My friend Ali Arikan wrote a touching piece in Slate on Friday about how beloved Sharif was in Turkey, even back when Lawrence of Arabia was banned in that country for its depiction of Turks. I wish I could tell you that, growing up as a Middle Eastern kid in Virginia, I, too, idolized Sharif, but that was not the case: He belonged to our parents’ and grandparents’ generation, and his demeanor spoke of an old-fashioned, nearly extinct brand of cool.

Indeed, he was a man slightly out of his times: His star presence recalled a classicism that Hollywood and the rest of the world was starting to shed right as Sharif came on the scene. (Lean, for his part, wished he had cast Sharif in more films — but of course, Lean himself only made two more films after Zhivago.) In his last couple of decades of life, he split his time between Cairo and a hotel in Paris. One wonders if, had he been just a few years younger or healthier, he might have had more opportunities to reemerge onto the international film scene. Even so, a few years ago, he gained acclaim once again for his role as a Turkish shopkeeper who befriends a Jewish boy in the drama Monsieur Ibrahim. It was a small, lovely drama, aided not just by the actor’s performance, but by our shared history with him. He was much older, yes, but here, again, was that noble manner — speaking to us of a half-imagined courtliness that the world had passed by.