The great superhero origin stories are generally reactive: Bruce Wayne’s parents are murdered, so he creates Batman; random happenstance grants Peter Parker great power, great responsibility ensues. Even Superman’s story is set in motion because his parents shunted him off before he could voice his opinion in the matter. And cinema’s most profitable superteam, the Avengers? They’re a semi-sanctioned militia who came together to fight a magical warlord. These protagonists were all subjects of chance and the whims of others. That’s not the case with Reed Richards, patriarch of the Fantastic Four.

Reed is, in his best tellings, the anti-Avenger. His origin is proactive and — for those who enjoy getting lost in his printed tales — almost utopian. This is a well-meaning scientist whose desire for human advancement is what inadvertently ends up granting him powers. This month’s Fantastic Four reboot is not just an embarrassing disaster, it’s also a lost opportunity to tell a story that audiences need far more than the militaristic, xenophobic bluster of the Avengers and Superman franchises. The time is ripe for Reed (and, to a lesser extent, the other three Fantastics), and it’s miserably depressing that his latest tale is destined for the dustbin of history.

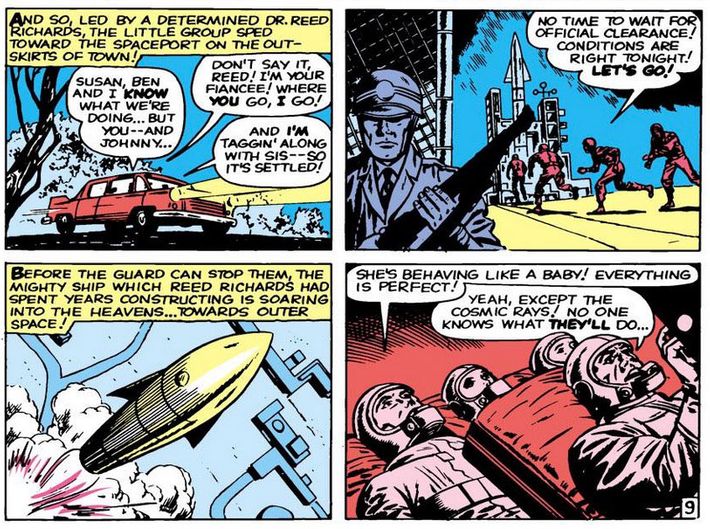

The specific historical details of the first Fantastic Four story, told by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in 1961, are antiquated, but not the core idea. It’s a tale in which a group of people take a risk to combat a pressing, conceptual danger for human progress, not to tackle a mustache-twirling villain or an epidemic of street crime. When Lee dreamed up the FF, the United States was woefully behind in the Space Race. To him, as to many Americans, the idea of the backward and tyrannical Soviet Union taking the lead in the new frontier posed an existential threat for the future. So, in Lee’s typewritten synopsis for The Fantastic Four No. 1, we meet “young, handsome scientist” Reed Richards, pursuing a “flight to the STARS” in an experimental rocket. He and his cohort — his girlfriend, her brother, and a pilot friend named Ben — “fear that if they don’t go, Reds may beat us to it.” The ship is untested. The launch site is off-limits. They go anyway. The cost of doing nothing is too high.

Of course something goes wrong. Cosmic rays give the quartet unwanted abilities. Quickly (comically quickly, but this was an era of compressed storytelling), Reed embraces Ben’s assertion that they “gotta use that power to help mankind.” Not fight crime, not combat threats; help on the grandest possible scale. Such have been the adventures (the interesting ones, at least) for Marvel’s First Family ever since: fighting anything that might hold us back as a species, be it (in the case of Lee and Kirby’s genre-changing “Galactus Trilogy” of 1966) world-devouring space giants or (in the case of Jonathan Hickman’s beautiful “Future Foundation” mega-arc of the early 2010s) the superhero population’s shortsighted focus on ass-kicking. Reed, in his best incarnations, is someone who — though often arrogant and eternally aloof — one-ups Spider-Man’s core idea: With great power brings massive, world-historical, and forward-facing responsibility.

In this era of superhero ascendancy at the multiplex, there are no tales that look forward. The Avengers franchise is a series of stories about people who are good at building or being weapons, and using them to mow down villainous hordes. In the X-Men franchise, Professor Xavier’s dream mostly amounts to let’s integrate a minority population and maintain the status quo. And Zack Snyder’s Superman and Batman … well, they appear mainly to be interested in punching and Randian self-actualization.

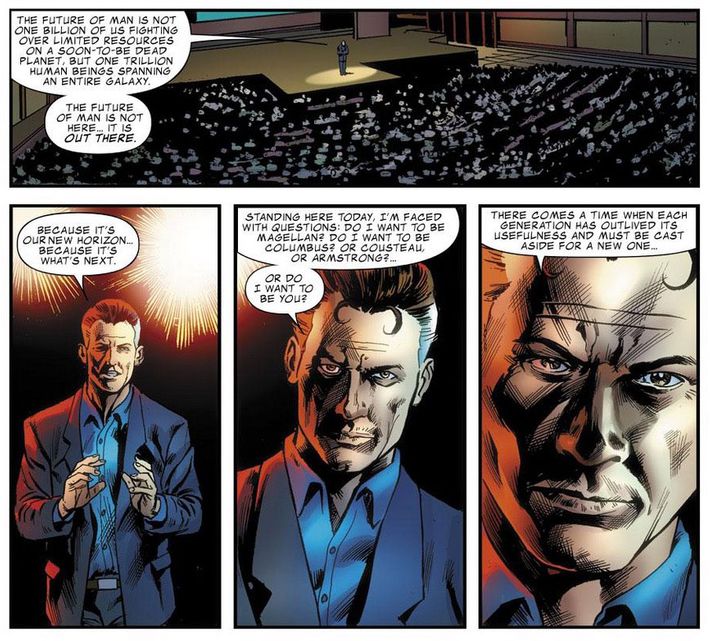

The new Fantastic Four seemed, back in its first trailer, to potentially be a new kind of superhero film. It began with voice-over asking, “How did we get this far?” then musing on humanity’s duty to explore and innovate. There were no invading armies, not even a bad guy. There was simply an impending encounter with the unknown and the unexpected. The teaser concluded with a promise from an unseen figure that the protagonists need to prepare not for a battle but for “the answers.”

Indeed, parts of the movie (and it increasingly seems this was a slapdash patchwork of at least two different attempts at a movie) stab at a story about advancement. Reed’s recruited by an aging benefactor who believes the baby-boomers have brought humanity to the brink of extinction through oppression, rapaciousness, and ignorance. He recruits intelligent young people who haven’t yet made Faustian bargains with the status quo and charges them with imagining a better world. There’s no rocket travel here, but the group’s ill-fated interdimensional jaunt happens because they believe they’ve found a world resembling primordial Earth, one that will help them find out where everything went wrong. Reed undertakes the jaunt because he doesn’t want military men going to the new world first (though that plot point is muddied by the fact that the journey is taken while Reed is drunk and eager to make himself famous). In the mostly incomprehensible climax, the villain wants to keep humanity away from that other world because we’re likely to foul it up just like we did with our current home world. These are interesting notions for a superhero film. Sadly, they’re garbled beyond all recognition. (To be fair, it’s very hard to do a superhero movie that isn’t reactive — after all, how do you propel an action flick if the “villain” is cultural myopia?)

But boy, it would be nice to have a good Reed Richards parable right now. On the day the abysmal reviews of Fantastic Four first appeared, Rolling Stone ran an article called ” The Point of No Return: Climate Change Nightmares Are Already Here,” and as I stared at it on my laptop screen, my chest contracting with despair and anxiety, I couldn’t help but wish that we, as a moviegoing culture, would bother to dream of being Reed Richards, not Iron Man or Captain America or Batman. Why must our big-screen crusaders wait for terrorists and mental cases to headbutt and punch? Is that truly all our superhero movies are capable of? With all of their intelligence and resources, what are Batman or the Avengers doing when their city or world isn’t being threatened? Is it too much to hope for a story where the goal isn’t to merely defend normality but to, as Reed scrawls on his laboratory wall* in Hickman’s first FF story, “solve everything”?

I’m not a filmmaker. I have no idea how to write or direct something on the scale of a tentpole superhero movie, so I can’t prescribe how a good Fantastic Four story can be told. But when I see writers I respect saying it might be time to retire the Fantastic Four from film, I think of something Reed says in that same Hickman tale:

“Most people don’t know how to solve problems. They tend to be overly concerned with how difficult their choices are, or the complex nature of their specific predicament, or if they even have it within them to find a solution in a limited amount of time.”

But, eyes full of hope, he suits up for an interdimensional journey and tells his family that such worries about difficulty “overshadow the reality of a single inherent truth. There’s no problem that can’t be solved.” Here’s hoping, Reed.

*An earlier version of this post misstated that Reed scrawled in his notebook, not on his laboratory wall.