It’s not always easy to sort fact from fiction in music biopics, particularly when the facts of musicians’ lives are often so bizarre. Elton John really did perform a concert dressed as Donald Duck. James Brown really was chased by police across two states. If anyone ever gets around to making a Van Halen biopic, the sequence depicting the band’s infamous visit to Madison, Wisconsin, in 1978 will likely seem like an invention, but it really happened.

Still, don’t believe everything you see. Even biopics that are at least somewhat committed to historical accuracy end up cutting corners. Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis, for instance, insinuates that Elvis Presley’s sleazy manager, Colonel Tom Parker (not his real name, though he was named an honorary colonel in the Louisiana State militia), arranged to have Elvis drafted into the Army to tame his out-of-control image, a detail that might be poetically true but doesn’t have much connection to fact. It’s part of a biopic tradition of bending the truth to serve the story and of compressing and condensing for the sake of narrative convenience. In the N.W.A biopic Straight Outta Compton, an incident of police harassment leads instantaneously to the composition of “Fuck Tha Police.” It’s one of the film’s best sequences. It’s also almost certainly not how it happened.

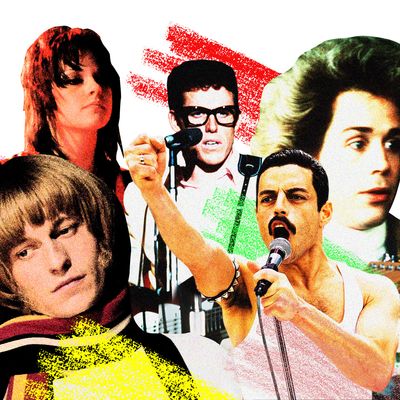

There’s a fine line between embellishment and outright fiction, however. Most biopics tread it. Some cross it. Some pretend it doesn’t exist at all. Below are ten from across the past 75 years that took the truth to the limit — and sometimes further than that.

Night and Day (1946)

Degree of accuracy: 64%

Night and Day is the Cole Porter story, broadly speaking. As played by Cary Grant, the film’s Porter is the happy-go-lucky scion of a wealthy Indiana family whose law studies at Yale get derailed by a love for song. He finds great professional success, but only after a period of initial frustration and time abroad, some of it serving in the French Foreign Legion. He has a long-lasting marriage to Linda Lee Porter (Alexis Smith), who celebrates each opening night by giving him a cigarette case. He faces physical adversity after a riding accident. All true, but Night and Day leaves out much, sanitizes more, and squeezes what’s left into the form of a Hollywood-friendly biopic that’s as a flavorless as Porter’s songs are memorable, despite the presence of Grant in front of the camera and the reliable Michael Curtiz behind it. In one especially groan-worthy moment, the young Porter says he doesn’t want to wonder what life would be like if he “hadn’t have been … fenced in.”

It’s what Night and Day leaves out that gives it a difficult relationship with the truth. Though by all accounts Cole and Linda Lee Porter had a loving, functional marriage, Cole was gay, and extramarital dalliances were part of their relationship. Linda was also several years his senior, and a divorcée, having escaped an abusive marriage. None of this could be depicted in the 1940s, of course, but Night and Day struggles to find anything dramatic to make up for its absence. The Porters’ marriage suffers because Cole can’t stop working on one successful project after another. It seems more envious than pitiable. Even after his accident, Grant’s Porter seems like a fundamentally merry fellow. Where the real-life Porter suffered tremendous physical pain that may have contributed to his alcoholism, Night and Day’s Porter is seen staying up carousing the night before the latest in a string of surgeries that mostly seem like minor inconveniences.

That everyone knew what they were doing adds an air of disingenuousness to the film. Porter’s longtime friend Monty Woolley, and actor and wit, plays himself. In one late scene, he shows up at the hospital and, thanked for some flowers, replies, “Yes, one can only send them to another man when he’s flat on his back.” Porter himself is said to have offered the best criticism of the film when he gave approval to the script with the words, “None of it’s true.” Strictly speaking, much of it is true. But that doesn’t mean there’s much truth to it.

Lisztomania (1975)

Degree of accuracy: 12%

Franz Liszt was many things: composer, performer, lover, patron. He was also, loosely speaking, a rock star. Heinrich Heine created the term Lisztomania to describe the effects Liszt concerts had on the screaming crowds that turned out to watch him perform, concertgoers who found themselves driven to delirium with enthusiasm.

He did not, however, fly down from heaven in a spaceship to do battle with Richard Wagner, who’d assumed the form of Frankenstein’s monster with Hitler’s features and taken to toting a guitar-shaped machine gun and killing Jews. That is the case, however, with the Liszt of Ken Russell’s demented Lisztomania, which opens with a sequence in which Liszt (played by the Who’s Roger Daltrey) licks the breasts of his mistress in time to a metronome, flashes forward to a concert that includes roadies wearing jeans and Franz Liszt T-shirts, and just gets stranger from there. Highlights include a cameo by Ringo Starr as the Pope, an extended homage to Charlie Chaplin, and a scene in which Liszt rides around on a giant golden cock.

Clearly, Russell and everyone else involved had no interest in the literal truth of Liszt’s life, which they used as a jumping-off point for wild fantasies. But anyone who doesn’t know at least a little bit about Liszt going into the movie will be lost, as it expects viewers to understand the life it’s sending up without ever explaining it to the uninitiated. Liszt did have a long, important friendship with Wagner, who married Liszt’s daughter, Cosima. He also had a complicated relationship with the Catholic Church, tied to his attempts to marry a previously married Russian countess (albeit one that never involved a Pope Ringo). But even armed with this knowledge, it’s tough to make sense of the film. Where future biopics like Todd Haynes’ Bob Dylan fantasia I’m Not There would use the lives of their subjects as raw material for nontraditional biopics, Russell’s film plays like excess for the sake of excess, losing sight of Liszt and whatever else it wants to say amid all the garishness.

The Buddy Holly Story (1978)

Degree of accuracy: 67%

Gary Busey won an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Texas-born rock-and-roll pioneer Buddy Holly, and deservedly so. He disappears into the role, even singing Holly’s songs himself. He also brings much more personality to the film than the script, which portrays Holly as an easily frustrated but otherwise virtually flawless fellow. That’s not that far off from most accounts of the real-life Holly, even if there’s more than a touch of Old Hollywood sanitization to this New Hollywood–era film. Holly’s band, the Crickets, on the other hand, don’t come off nearly as well. Having previously sold their life rights to another project, J.I. Allison and Joe B. Mauldin became, respectively, “Jesse Charles” and “Ray Bob Simmons.” Allison, the Crickets’ drummer, had particular reason to hate the film, since his analogue was depicted as a racist. “I thought it was a horrible movie. I didn’t see anything that was correct. I imagine it was made up,” Allison said. “It’s kind of sad for us.”

Amadeus (1984)

Degree of accuracy: 53%

Sometimes the truth needs a little reshaping for the sake of art, however. Adapted from Peter Shaffer’s play of the same name, Milos Forman’s 1984 film Amadeus works brilliantly as a study in contrast between genius and a more mundane sort of workaday talent. In the latter role, Amadeus drops Antonio Salieri (F. Murray Abraham), an Italian composer (and later tutor to Beethoven, Schubert, and Liszt) serving in the court of the Hapsburg monarchy, played here as an uptight, sexually frustrated prig. Filling out the former role: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, played by Tom Hulce as an occasionally buffoonish wunderkind of astounding gifts. Astonished by and jealous of Mozart’s talents, Salieri does everything in his power to thwart Mozart’s success — and later commissions a requiem mass he plans to claim as his own.

In fact, Mozart and Salieri seem to have been quite cordial. Mozart lost a teaching position to Salieri, possibly as part of an ongoing rivalry between Italians and Germans in the court. But he also worked with Salieri on a now-lost cantata and, per Mozart’s letters, gave Salieri a ride to the premiere of his Magic Flute, which Salieri enjoyed enthusiastically. And while it’s impossible to overstate Mozart’s greatness, it is possible to understate Salieri’s contributions by playing him as a creatively constipated hack. So while there’s little accuracy to Amadeus — or previous dramatizations that posited Salieri as an envious rival — the film still gets at a greater truth about creativity and jealousy, showing how beauty can be horrible to those who can’t create it, and that the success of others can feel like a personal insult from God to those who can’t achieve it. Sometimes truth runs deeper than facts.

Hysteria: The Def Leppard Story (2001)

Degree of accuracy: 68%

Made for VH1 during the glorious Behind the Music–dominated stretch when the network transformed into a channel for music nerds, Hysteria: The Def Leppard Story isn’t so much inaccurate as hilariously compressed. Even by music-biopic standards, it squeezes a lot of ups and downs into a short running time. Our heroes meet, form a band, hook up with producer Mutt Lange, experience tragedy (an accident in which drummer Rick Allen loses an arm), and (mostly) get their act back together at a pace that sometimes makes the movie feel as if it’s on fast-forward. The unforgiving TV-movie budget and spotty accent work doesn’t help, either. The band didn’t love it: In 2019, frontman Joe Elliott called it “the biggest pile of shit ever made.”

Stoned (2005)

Degree of accuracy: 70%

If ever a rock star were likely to die by drowning in a swimming pool after ingesting a stunning amount of drugs and alcohol, it was Brian Jones. The Rolling Stones guitarist parted ways with the band in 1969, when his out-of-control behavior estranged him from the other members. (Take a moment to let that sink in.) But where there’s a dead rock star, there’s a conspiracy theory, which has led to a lot of speculation about who really killed Brian Jones.

One popular choice: Frank Thorogood, a builder living at Jones’s estate — formerly the home of Winnie-the-Pooh creator A.A. Milne — at the time of the guitarist’s death. Stephen Woolley’s film eventually buys into that theory after a long stretch of portraying Jones (Leo Gregory) as a self-destructive character with little regard for his own life. Paddy Considine plays Thorogood as a man quietly seething with rage and class resentment who one day just snaps. The problem: There’s not a lot of evidence to support that, apart from a dubiously sourced deathbed confession. And apart from Considine’s standout performance, there’s little here to set this apart from any other story of ’60s rock-star excess. Jones never emerges as a distinctive character. The facts might be straight, up to the questionable finale, but Stoned never finds a story worth telling.

The Runaways (2010)

Degree of accuracy: 29%

Where the accuracy of Stoned can be called into question by a suspicious inclusion, it’s a conspicuous exclusion that now makes The Runaways look less than truthful. The story of an all-female rock band that briefly took the ’70s by storm, the film was adapted from singer Cherie Currie’s memoir, Neon Angel, of her time with the band, and executive-produced by Currie’s former bandmate Joan Jett. It makes a certain amount of sense that focus would fall primarily on their characters and offer a simplified take on the band’s origins and history. (Early member Michael Steele, who later joined the Bangles, is conspicuously absent, for instance.)

In promoting the film, both Currie and Jett have been fairly upfront about presenting it as an interpretation of their experience rather than an airtight account. Speaking to Hitfix before its release, Currie both noted that its emphasis on the grim side of being a rock star isn’t entirely accurate and pointed to places where writer/director Floria Sigismondi softened the story, like when she chose to leave out that Currie was raped by her sister’s boyfriend. Taken on those terms, as a loose interpretation of the Runaways’ story, it works well enough, in part thanks to Dakota Fanning and Kristen Stewart’s performances as Currie and Jett, respectively.

The other notable performance comes from Michael Shannon as Kim Fowley, the Runaways’ Svengali, who sees a million-dollar idea in putting together a band made up up of sexually provocative underage girls. The film depicts him as a colorful, selfish, possibly malevolent character but downplays any suggestion of sexual menace. Since Fowley’s death earlier this year, a different story has started to emerge, via a Huffington Post story in which Jackie Fuchs (who played bass with the Runaways under the name Jackie Fox) claims Fowley raped her while Currie and Jett looked on. Fuchs refused to participate in or lend her name to the film; Alia Shawkat plays the fictional bassist Robin Roberts instead. Her absence now looks more conspicuous than ever.

CBGB (2013)

Degree of accuracy: 19%

It’s probably easier just to point out what this purported history of Hilly Kristal and his famous club gets right than all it gets wrong. Yes, there was a club called CBGB. Yes, famous acts like the Ramones, Patti Smith, Blondie, Television, and Talking Heads played there. Yes, Kristal managed the notorious-even-for-this-scene act the Dead Boys. Beyond that, well, you won’t learn a lot about punk or what CBGB meant here.

The problem’s as much a matter of focus as accuracy. The film offers a parade of famous and semi-famous faces playing everyone from Debbie Harry (Malin Akerman) to Iggy Pop (Foo Fighters’ Taylor Hawkins), and the decision to let them lip-sync to the studio versions of famous songs doesn’t help create a gritty, downtown vibe. (Nor do anachronisms like having a pre-fame Patti Smith (Mickey Sumner) sing “Because the Night,” her biggest hit and a song co-written by Bruce Springsteen.) But CBGB barely seems to notice what makes any of them important, so intent is it on lingering on Alan Rickman’s Severus Snape–with-a-hangover routine as Kristal. Given a front seat to history, all he can do is look annoyed. Watching the film, it’s hard not to share his feelings, as CBGB misses the point in scene after scene.

While there’s little reason to recommend the film — which provided fodder for an episode of the great bad-movie podcast “The Flop House” — as a work of art, and it earned scathing reviews as a result, some of its bad press came from those who recognized how far it missed the mark. The Village Voice’s ”10 Things the CBGB Movie Got Wrong” typifies the scrutiny faced by any based-on-fact movie in the internet age. Whether it’s hiding a subject’s sexuality or putting the wrong stickers on a club’s bathroom wall, these days, someone’s going to notice. And whether the subject is Cole Porter, Johnny Cash, or Ice Cube, facts will continue to be bent for the sake of drama, but outright wholesale invention might be a thing of the past.

Phil Spector (2013)

Degree of accuracy: 18%

“This is a work of fiction. It’s not ‘based on a true story.’ It is a drama inspired by actual persons in a trial, but it is neither an attempt to depict the actual persons, nor to comment upon the trial or its outcome.” So reads the bizarre disclaimer that opens Phil Spector, David Mamet’s attempt to … well, that’s hard to figure out. The film, starring Al Pacino as Spector and Helen Mirren as defense lawyer Linda Kenney Baden, depicts Spector’s trial for the murder of actress Lana Clarkson and at least seems to be an attempt to get at the facts of the story and make a case for the famed music producer’s innocence.

In scene after scene, Baden delves into inconsistencies in the blood spatter on Spector’s clothes, re-creating Clarkson’s death with (gross) animation and by using a lifelike dummy to prove the wound had to be self-inflicted. It plays like a detective story with occasional interruptions of unmistakable Mamet dialogue. It also omits many, many details that make Spector look guilty of murder (as a jury agreed during a second trial after the first ended in a hung jury). But, hey, Mamet says it’s a work of fiction before the movie even begins, so he can do what he wants, right?

Bohemian Rhapsody (2018)

Degree of accuracy: 62%

Directed (at least nominally) by Bryan Singer, this massively successful Queen biopic employs a lot of narrative shorthand and simplification in telling the story of the band’s rise to fame. That’s to be expected in rock biopics. And at least in band-approved biopics like this one, it’s not unusual for movies to elide nagging details like Queen’s willingness to play apartheid-era South Africa when other acts went out of their way to avoid it.

But it’s in the home stretch that Bohemian Rhapsody leaves reality behind almost entirely. The band breaks up then overcomes their differences just in time for a triumphant performance at Live Aid, a concert they perform shortly after lead singer Freddie Mercury (Rami Malek) learns he’s HIV-positive and reveals his diagnosis to his bandmates. In reality, Queen never broke up, and Mercury didn’t learn of his diagnosis until years after Live Aid, then didn’t share the news with the rest of Queen until sometime after that. The real story isn’t quite as neat as the one in the film, but hey, as Mercury himself sang, the show must go on.