Since rock is dead and all, it seemed fitting to meet Savages in a graveyard. The London post-punk favorites are dressed for the occasion in their signature all-black attire, gathered on a blanket in the scorching late-August sun, between Hollywood Forever Cemetery’s iconic statue of the late Johnny Ramone and a memorial pond full of white swans. The prevailing mood, however, is less than somber.

“That’s the Queen’s, don’t touch it!” blurts bassist Ayşe Hassan as front woman Jehnny Beth makes moves toward the pond bank and the massive birds. Hassan pauses, turning back to me. “Do the ones in America belong to the Queen as well?”

“She owns all the swans, even the band,” deadpans guitarist Gemma Thompson.

The four women have been traveling almost nonstop for the past week or so, during which they’ve played their final Stateside shows (six here in California, one in Vegas) of the year, and they are exhausted, not to mention a little punch-drunk. They’ve just finished lunch at Café Gratitude, the L.A. spot famed for its vegan food and intensely self-actualizing menu.

“Best food ever, but … the most Portlandia place,” says Hassan, wide-eyed.

“‘I Am Terrified,’” quips Thompson, parodying the café’s dish-name format.

“‘I Am Embarrassed,’” Hassan echoes.

Still, this unexpectedly goofy tangent did begin, perhaps more predictably, in a serious place: Before she went for the swans, Jehnny Beth had been saying that they “like to be conscious.” Regardless of whether that sounds like a Christian-rock subgenre (as Thompson jokes), Savages are indeed nothing if not wide awake — and paying close attention.

“When we first played Primavera [Sound, the Porto, Portugal festival], there was so much cheering from the crowd; I remember thinking, What do we do with this? How do you take that love and give it back?” Beth says, sitting cross-legged and on the blanket, her forearms resting on her knees. Her posture is casual, but even assembled here in the sunlight, the band exudes an intellectual seriousness that makes it hard to believe they’re ever truly at ease. “We’re giving it back with music, but I mean, like, how do you do that and still stay yourself? That was the whole question, and the whole dilemma.”

It’s a roundabout way of explaining the band’s approach to their forthcoming sophomore album, Adore Life (out January 22 via Matador), announced just yesterday. While adaptation plays a substantial role in any artist’s evolution from first to second album, for Savages — a band whose 2013 debut record, Silence Yourself, received overwhelming acclaim for its militant, unflinching approach to feminist post-punk — that process has been especially important.

Savages was born in late 2011, after Thompson approached Beth with the band’s confrontational concept. By that point, Beth had grown bored of writing love songs for John and Jehn, her duo alongside partner (and future Savages producer) Nicolas Congé, a.k.a. Johnny Hostile. She threw herself into this more aggressive art; by January 2012 they’d collected Hassan and drummer Fay Milton and played their first show.

After Silence Yourself’s release on Matador Records in May 2013, the band went out on the road and hardly stopped to breathe for the next year and a half. Somewhere between playing nearly every continent and major festival, Savages became known as one of those bands you have to see live due to their intensity. Their shows are loud in the way that cleanses your system or shakes you up, but there’s also a bit of nuance in the songs — they’re not simply brutal force. After cultivating a mythology around themselves straight out the gate, how does such an uncompromising band approach a sophomore LP that has big expectations attached?

Believe it or not, they assembled a focus group of sorts.

After their world tour wrapped last spring, the quartet returned home to hole up and write for six months. By the end of 2014, they had a loose collection of songs in the bank but little interest in going straight to the studio. “We had to work out a way to feel comfortable,” Thompson says. What they settled on was an intimate club residency in New York, where they test-drove the new material (and at times heard themselves openly objectified). Unlike the gigs that previewed Silence Yourself, these nine shows spanning three weeks quickly sold out.

“We would play only the new songs, and go back to the rehearsal space the next day, reshape some songs, try them again the next day,” Hassan says. “I really enjoyed it. People even bought tickets for every show, so they would see the evolution of the songs [as we] rehearsed. We got a lot done like that. When you have an audience, it keeps you on your toes.”

The band treated the shows like a one-way mirror, taking mental notes on the attention of the crowd — already enthusiastic after having fought to get tickets for these events — waxed and waned throughout the set. “It is almost subliminal,” Beth says. “It goes in, [and we] just get the feeling of what’s working and what’s not.”

It seems like an odd strategy, letting other people weigh in on music driven by a precise artistic vision and a confrontational approach to ideas about love, gender, and power (though Beth wouldn’t call it strictly feminist, instead describing Savages as “women … living a little bit louder”). But the band seems to have more faith in people than they did two years ago.

“It changed us, to tour around the world and be in contact with different kinds of audiences who have such a strong affection for our music,” says drummer Fay Milton. “That shaped us, and made us a bit more relaxed, and a little bit more humble.”

In a way, the experience echoed Beth’s own upbringing being taught that creation is never not a communal effort — specifically, by a house full of “theater people,” her parents and their menagerie of guests. She recalls family dinners in which actors, writers, and comedians crammed around the table, often sharing stories about their art and arguing over craft. “As a child, I was really entranced by that,” Beth says, “the idea that you create this thing together.”

But the truth is, Silence Yourself’s sounded like it could have been created in a clean room, completely detached from the ever-frustrating world — that’s how urgent it was. Its follow-up isn’t any less forceful — song titles include “Evil” and “Surrender,” lyrics still include lines like, “Love is a disease / the strongest addiction I know” — but this time the band feels more responsive, empathetic, almost patient, as though their first round went so well that they suddenly realized they don’t have to fight so hard to make the audience pay attention. And so Adore Life doesn’t shy from quiet moments; with each track, Beth’s own voice comes across in the mix clearer — and more vulnerable — than ever, wrestling with the prospect of loving and being loved by another.

Silence Yourself frequently relied on third-person narratives that reflected the band’s discontent but seemed more symbolic than confessional, a step removed from the tragedy. Adore Life, however, is intimate and up-close, without losing any of the backbone of its predecessor. “Sad Person” is a direct, wounded call-out; “When in Love” excavates fears of intimacy and falling in love; yet on the title track, Beth asks, “Is it human to adore life?/ I adore life,” like the punk Maria von Trapp. The cavernous anger Savages is known for now feels electrified with an almost desperate will not only to survive, but to transcend.

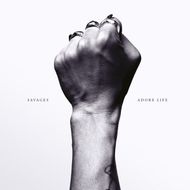

Its album art fits the incongruity perfectly: a single bony fist raised to the sky, veins bulging with the force of the upward punch, silver rings on three fingers like brass knuckles … but flanked by the title, in tiny, elegant serif: A D O R E L I F E. “There is a romancing to it,” Beth admits. She thinks about it, and then launches into a more complicated explanation of the record’s origins.

“I remember reading [Ray Bradbury] interviews where he said the first time he wrote was because he went to see the circus,” she says. “He was a child, and a [drunk] clown came to his face, and he turned suddenly to him and said, ‘Live forever.’ He went home that night and started writing stories. He explains that that’s the moment where things started for him.”

Not satisfied with that analogy, she tries another: evoking the life of lesbian poet Minnie Bruce Pratt, whose romance with famed trans activist/author Leslie Feinberg came late in life, after years of heterosexual marriage and children.

“They were both accidents that happened to them, and they couldn’t control it, really,” she says of Pratt and Bradbury. “That’s a kind of romance, the idea of an event arriving in your life that changes everything. You have to adapt to that new thing, and through that event you become an artist. That’s the center of the idea of the record: There’s not a science for living and a science for creating. They’re both the same thing.”

While the band has grown, some things have stayed the same, of course — namely, their bite-back against old stereotypes and pronouncements about the death of rock music.

“I think it’s the funniest thing,” Milton says. The inventive percussionist (and the last to join the band) chimes in only occasionally throughout the afternoon, but at this topic, she visibly perks up. “How many years did the violin have, doing what we do? Guitar music has existed for 50, 60 years? You never hear, ‘Classical music’s dead. All the ideas have used up already.’”

“It’s so daunting,” Beth agrees. “‘You’ll never have such a great time as your parents had. That’s it. It’s over. You can’t create your own culture.’ But that situation is actually interesting because it makes you create your own culture. People, they see the world ending and have accepted their own end. They like to say this is over. No, you’re over.”