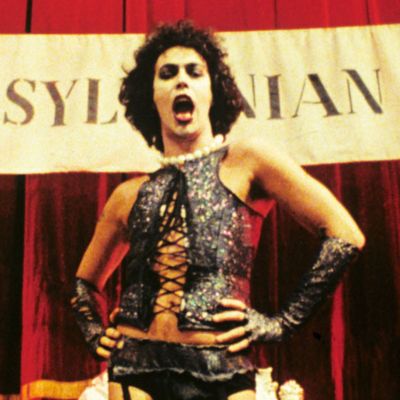

About 20 minutes into the film The Rocky Horror Picture Show, an elevator door opens and the actor Tim Curry steps out. His face is heavily mascaraed, the portrait of a commedia dell’arte drag queen. Everything below that striking visage is covered in a magnificent cape. He struts out, to the beat of a Stonesian guitar riff, and a few moments later he turns and rips off the cape: We can see he sports a glistening string of giant pearls and, not least, a silver-spangled ensemble of women’s lingerie.

In the mid-to-late 1970s, as a high-school teen, I was one of those thousands who, Friday night after Friday night, would assemble at a local repertory theater to see, for the fifth, tenth, 20th, or 35th time, this stunning manifestation.

I saw The Rocky Horror Picture Show again recently and tried to parse its force. There’s Mick Jagger in Curry, sure, but there’s also, in his homoerotic pose, something of another epitome of screen masculinity, the gauzy first glimpse we get of John Wayne in Stagecoach.

Anyway, this summer marked the 40th anniversary of the release of the movie. It was originally a campy U.K. production called The Rocky Horror Show. The movie version, which was brought to America by producer and manager Lou Adler, became an unaccountable cult hit for years, and then decades, and now takes a place on the list of the most profitable films of all time. While this anniversary has been duly noted, the film’s real sociological significance has not been. Since I was growing up in the cultural wasteland of Phoenix, Arizona, at the time, I can speak about this importance with some authority.

***

At our high school, to which I walked each morning across a mile or so of scrub desert, the unusual kids clustered in the drama club. At the time, just about all of us, I think it’s fair to say, looked at the gay demimonde in a way that other white suburban kids would begin to look to the hip-hop underworld a decade or so later; it was everything we thought was cool in the world. And boy, did it irritate parents and some of the other kids.

It was all innocent; hardly anyone was having sex, much less gay sex, and I myself wasn’t gay, but even then we knew that the majority of the boys in our club in some way were or would be. It didn’t matter because we were all in it together. We streaked our hair or wore eye makeup to school. The earring I got my senior year nearly gave my father a stroke. (Today earrings are a frat-boy accouterment; back then it was highly unusual to see one on a man, much less a male teen.)

For my graduation photo I wore makeup and eye shadow, and I wish I could say I matched the androgynous gorgeousness of David Bowie or Todd Rundgren. But with my puffy hair and Coke-bottle glasses, I just looked like Tootsie’s homely niece.

We were, in a safe, suburban way, misfits, and to some extent outcasts. I was never beat up precisely for the way I dressed or the people I hung out with, but it was the kind of environment that could occasionally get you called “fag” and slammed into a locker for no reason by one of the sports guys, generally when there was a group of girls around.

And then we discovered The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The film, if you haven’t seen it, is a potent but gentle rock musical with a slate of irresistibly catchy songs. The story is a pastiche: a magnanimous spoof of old-time horror and sci-fi movies. Many of those old movies were black and white, but it’s one of the film’s charms that it’s filled with jarring colors and a goofy cast of characters. It opens with a pair of luscious red lips singing the opening song, which name-checks some of the film’s beloved predecessors:

Michael Rennie was ill

The Day the Earth Stood Still

But he told us where we stand

And Flash Gordon was there

In silver underwear

Claude Rains was the Invisible Man …

The story follows a hopelessly square couple, Brad and Janet, who get a flat in a rainstorm and end up at a mysterious mansion. This turns out to be the domain of Curry’s character, who is a mad scientist, Dr. Frank-N-Furter, who oversees, in sometimes sadistic fashion, a cast of supporting freaks. One of these is his Igor-like assistant, Riff Raff, played by Richard O’Brien, the show’s creator. They are aliens, we are given to understand, from the planet Transsexual in the galaxy of Transylvania. (There’s some intimations that time travel is involved as well.) The film’s masterful, lancing conceit is to make Frank-N-Furter a hugely likable, genially sex-crazy transvestite who preaches a mantra of “absolute pleasure.” His fateful project is to create a Frankenstein’s monster — a hunka-hunka burning bodybuilder named Rocky. Frank-N-Furter’s issues are sometimes just kinky — there’s a set of video feeds that capture the mansion’s various shenanigans on video, for example, and he’s not above making his guests perform in a naughty floor show. But they can also be more severe: He can be homicidal and even — gulp — a cannibal, but we forget that as he cheerfully debauches both members of the young couple. The good doctor looks spectacular in a bustier, but things don’t end well. He’s deemed “too extreme” by his overlords and is spectacularly dispatched by Riff Raff.

If that reminds you of David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust (“He took it all too far/ But boy could he play guitar”), it should. Like David Bowie and not too many other cultural artistes of the time, Rocky Horror was a resonating bid to bring polymorphous perversity into the mainstream. I could be wrong, but I think that Curry’s mien — rough-featured, hirsute, and plainly masculine through the makeup — is a first in pop culture. Am I forgetting someone, or is he the first time we saw an unmistakably manly figure so wholly occupy a plainly sexy female ensemble? Now, abandon and voraciousness don’t equal sexual orientation, of course; the whole point of the movie is to spoof that very idea. It’s message of acceptance is plain. At a time when many forbidden activities were consigned to shadows, it’s no accident that the show’s most striking musical moment is sung by O’Brien. It goes: “Let the sun and light come streaming into my life.” This openheartedness gave substance to the camp; the send-up of conventionality captured the imagination of a certain subset of a generation, and resonates to this day.

At those midnight showings of Rocky Horror we discovered something else, too: that there were misfits like us from every high school in town. The gay, the questioning, the hangers-on, the proto-punks, the wannabe-intellectuals, the disdained, and the otherwise shy convened to delight in Brad and Janet’s individual deflowerings; to mourn the martyrdom of Eddie (played by a very young Meat Loaf); and to swoon, week after week, at Frank-N-Furter’s lubricious entrance and the signifiers of his signature song, “Sweet Transvestite.” (My favorite was Curry’s droll reading of the line, “We could take in an old Steve Reeves movie.”) And we’d jump up to dance the Time Warp with the cast, shout recriminations at this or that character, don party hats with the actors as they did onscreen. The guys who might have been gay certainly marveled at Curry’s beefy physique, and those of us who weren’t could ogle Susan Sarandon, who ran around most of the film in her underwear. If nowhere else, at drama club, and at Rocky Horror, we had a tribe.

***

From this I jump to another memory: a senior-year field trip to see A Chorus Line, which had redefined the musical on Broadway and had just made its first appearance in Los Angeles. After the show, we gathered, electrified, for a dinner at a restaurant in Hollywood. I sat at one end of a long table as the gruff, burly head of the school performing-arts department sat at the other.

And we all remember what happened when I asked the question on everyone’s mind. “Mr. ___, Mr. ____,” I said. “Why did you and your wife not clap for A Chorus Line, clearly the greatest work of art in the history of the world?”

The department head didn’t miss a beat. “I will not applaud anything that tells me that 25 percent of the men in my chosen profession are homosexuals.”

Afterwards, many of us recalled, in the silence that followed his remark, mentally slapping our hands to our foreheads. There were two reasons. One, even then we all knew that 25 percent was a very low estimate of the number of gays in musical theater. Besides that, we also knew in our hearts that more than 25 percent of the men at the table were gay.

There was a casual, thoughtless cruelty in the moment that stays with me to this day. We were used to feeling secure in a little enclave; here was a reminder of a darkness outside. I know that the moment hurt some of the people who were there.

I also know that, in context, it was actually benign, considering. In the decades before that night and the decades since, hundreds of thousands, even millions, of gays and lesbians have been taunted, humiliated, ostracized, and cast out of families, schools, communities. And even they are the lucky ones. Others were institutionalized, lobotomized, castrated (sometimes by governments and churches), or simply brutalized and murdered. I think of the many who died alone. I think in particular of one of us, a straight-A student from a moneyed and conservative family, who often took the lead in musicals. He went to the Air Force Academy but was kicked out. Fifteen years later he died, and his obituary didn’t say what the cause of death was.

Internationally, the vulnerability of gay people in some countries is dire. Russia is seeing state-sponsored waves of bigotry and cruelty, and in other countries in Africa, some actually egged on by sociopathic American Christians, have made the practice of homosexuality a capital crime.

And yet in the U.S, things are unquestionably better; for a new generation homosexuality is what it should be, which is nothing special or notable. And with the same-sex-marriage ruling, we are definitely past a tipping point. It’s been 40 years since Rocky Horror reassured some vulnerable young people that beyond the shadow beneath which they lived there was light.

There’s a lot of people making noise about a baker in Ohio, or a county clerk in Kentucky, who have made life difficult for themselves in this new world. Unmentioned in that noise is the centuries of persecution, a quiet holocaust that attenuated or simply destroyed so many lives. In a stark turnaround from the 1970s, the world I grew up in, today it’s these folks who have the problem.

Fortunately for them, there’s a cure. The good doctor will see you now.

A Postscript:

After I wrote this piece, I flew to Chicago, staying at swanky hotel downtown. The hotel was run, coincidentally, by another high-school friend, not part of the drama-club crowd, I hadn’t seen or talked to in 30 years. He’s gay and happily affianced; turned out he was VP of a chain of similar hotels.

My wife and mother-in-law and a friend were sitting on a rooftop patio when my friend came in. We greeted each other; he sat down and, before anyone could say anything, began talking. It was something he’d been wanting to say a long time: “Bill changed my life. It was senior year, and he took me to this weird movie. It was called The Rocky Horror Picture Show. I had no idea there was a world like that out there, and I was never the same after. I literally would not be here today if it wasn’t for that night …”