To accompany Frank Rich’s essay on Carol, the Todd Haynes adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s classic lesbian novel, New York invited 28 people to share a specific piece of lesbian cultural history that moved them most. Here are their answers.

Spring Fire by Vin Packer (Marijane Meaker), 1952

If you were a lesbian in the 1950s, you were almost certainly bewildered, isolated, and desperate for information. And then, out of the miraculous blue, came the lesbian pulp paperbacks, written by and for women you recognized, women in love with other women, women of energy and passion. Their joy in each other overcame the crises in their lives. In Spring Fire, I read about two beautiful college students. I was too naïve to recognize them as classic models of butch and femme, but no depths of ignorance could mask the delight and relief I felt, reading about their emotional life. —Ann Bannon, novelist, the “Beebo Brinker” series

The “Beebo Brinker” series by Ann Bannon (Ann Weldy), beginning 1957

Beebo Brinker, the protagonist in this series, was tall, handsome, and very butch. She refused to wear dresses or skirts and would not take a job that required her to wear “feminine” clothing. When I was coming out in the early 1980s, I was smitten and spent many nights fantasizing about what it would be like to be her girl. Thank God for Beebo! —Lesléa Newman, author, Heather Has Two Mommies and October Mourning: A Song for Matthew Shepard

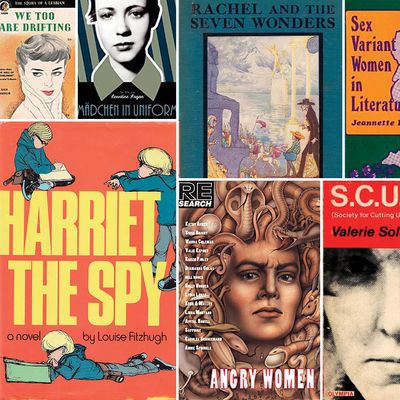

Harriet the Spy by Louise Fitzhugh, 1964

I knew there was something up with Harriet, and I didn’t have the language to talk about it. But there was some way that Fitzhugh constructed that kid that was really a portrait of the artist as a young lesbian. The way she felt about her friends — nothing was romantic or weird, but it was really clear. —Christine Vachon, co-founder of Killer Films; producer, Carol

Eye to Eye: Portraits of Lesbians Photographs by JEB, 1979

The women in these portraits were some of the first dykes I ever laid eyes on, and the book felt like a lost family album. Joan E. Biren, who went by JEB, explained how she got started photographing lesbians: I had never seen a picture of two women kissing, and I wanted to see it. So she took a picture of herself kissing her lover. —Alison Bechdel, graphic novelist, Fun Home and Dykes to Watch Out For

Sex Variant Women in Literature by Jeannette H. Foster, 1956

Foster — an unobtrusive dyke-librarian for many years at the Kinsey Institute for Sex Research—had to publish this magnificent bibliographic survey and labor of love herself (no legitimate publisher would touch it), and it has remained sublimely out of print pretty much ever since. Yet Foster offers nothing less than an encyclopedic history of lesbianism in Western literature from Greek antiquity to the 1950s. The mode is at once scholarly, compassionate, and weirdly ravishing. When I encountered this lovely, dignified, unpretentious work in my 20th year — consigned to a locked cage of “non-circulating,” sex-related books in my college library — it changed my life. —Terry Castle, author of The Literature of Lesbianism: A Historical Anthology From Ariosto to Stonewall and The Professor: A Sentimental Education

Rachel and the Seven Wonders by Netta Syrett, 1923

Syrett, a “New Woman” English novelist and playwright, put all her soaring feminism and sex-and-gender-liberating imagination into Rachel’s adventures in the ancient world—accessed through a secret portal in the British Museum by a mysterious magician. The Aubrey Beardsley–style illustrations by Joyce Mercer are as emancipating as the text. For girls and others. —Joan Schenkar, playwright, Signs of Life; biographer, The Talented Miss Highsmith

Bagdad Cafe, 1987

Even though there’s no great romance or sex scene, the care the two women in this film have for each other—that somehow they were more complete together than they were apart—really impressed me. It’s strangely romantic, as is the setting and the song, “Calling You.” —Rose Troche, filmmaker, Go Fish; producer Concussion and The L Word

I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing, 1987

Up until this totally lost gem by Patricia Rozema came out, pretty much every lesbian movie was about lesbians who didn’t know they were lesbians and had been in a horrible relationship with a really shitty man. I loved the political statements that this film made, and the fact that there were lesbians who were lesbians with no other explanation. —Lea DeLaria, singer and actress, Orange Is the New Black

Zami: A New Spelling of My Name by Audre Lorde, 1982

A smart black gay girl from the Caribbean, growing up in NYC and dealing with the racism at Hunter High School, having affairs with other girls and learning to be a poet. Both author and subject wanted adventure and agency. They didn’t yearn to get married, be monogamous, join the military. They broke rules. —Sarah Schulman, novelist, People in Trouble and The Cosmopolitans (forthcoming)

Say Jesus and Come to Me by Ann Allen Shockley, 1982

A steamy novel that took on race, patriarchy, religion, and sexuality — and had, at its center, two black women falling in love: This book was truly a revelation. And a sexy one at that. —Yoruba Richen, director, The New Black

Shockproof Sydney Skate by Marijane Meaker, 1972

I wish my first glimpse of lesbian culture had come from this hilarious, glamorous, and aspirational novel about a teenager who, unbeknownst to his mother, has unlocked the secrets of the coded language she uses when gossiping with her lesbian circle. Those witty, beautifully attired, hard-drinking New Yorkers sometimes found true love and sometimes got their hearts broken, but they always seemed glad to be gay. (Instead, it was Going Down With Janis, a biography of Janis Joplin that had been passed around school so many times the pages featuring lesbian sex scenes were almost transparent.) —June Thomas, editor, Outward at Slate

We Too Are Drifting/Torchlight to Valhalla by Gale Wilhelm, 1935 and 1938

Originally published by Random House as hardbacks, Wilhelm’s first two novels were written only ten years later than Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, but were worlds away in their lesbian-centric happy endings. These books are great to read both because they are classic—and not unhappy—lesbian stories and because it is remarkable to realize just how they were received at the time. Despite their lesbian content, even Kirkus Reviews wrote positively about both novels. —Eliza Byard, executive director, GLSEN

Les Guérillères by Monique Wittig, 1971 (English translation)

When I first read the short blocky paragraphs that make up Wittig’s all-out Amazonian war of the sexes, I was blown away by the language: incantatory, raw, and sexual, and yet also weirdly clinical at times. Then I read The Lesbian Body, its logical sequel of sorts—a novel about invading a lover’s body—and I thought the world had shattered. Here was a frankly lesbian love so darkly celebratory, so fierce and violent, that it couldn’t be contained by corporality. —Achy Obejas, novelist, Days of Awe

Personal Best by Team Dresch, 1995

Team Dresch was a rock band from the Pacific Northwest consisting of four out-and-proud lesbians. This record changed my life; it marked the first time that a narrative didn’t require an act of subtle translation. I didn’t have to reimagine that the longing was about a girl because the longing was in fact about a girl. It’s one thing to listen to music and think, This is who I want to be, and another to listen and to know, This is who I am. —Carrie Brownstein, actor (Portlandia, Carol), musician (Sleater-Kinney), memoirist, Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl

Angry Women by Andrea Juno, edited by V. Vale, 1991

It is hilariously dated in some ways (the Medusa cover), and more seriously so in others (the urgency of AIDS), but the fact remains that nearly every single artist profiled in this anthology either was or has since become incredibly important to me. —Maggie Nelson, memoirist, The Argonauts

Mädchen in Uniform, 1931

I first discovered this in the women’s film festivals of the 1970s, pierced to the heart by the scene of a besotted Manuela winning a kiss good-night from Fräulein von Bernburg, everyone’s favorite boarding-school teacher. I began to track the film like a private eye. Soon I was pounding out an essay on a heavy typewriter balanced atop boxes in the bare Chicago apartment into which I’d just moved with my first full-time woman lover. The relationship didn’t last. The film did — and propelled me into a career and, incidentally, into an eternal love of smitten women. —B. Ruby Rich, author, New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut; editor, Film Quarterly

S.C.U.M. Manifesto by Valerie Solanas, 1967

Too crazy, too angry, too deviant, too lesbian — Valerie Solanas, the woman who shot Andy Warhol, has been a notorious footnote in feminist history. I grew up in the 1970s, when the images of outsider girls in the public sphere were exploding all over the nightly news. I wanted so much to find meaning in the stories of radical women who might show me something about living out of bounds. My view of female rage changed forever when I discovered Solanas, the killjoy whose S.C.U.M. Manifesto was payback for the brutality of an unjust world, written by a woman who wouldn’t apologize or just fade away. —Amy Scholder, literary editor

Star Trek: The Next Generation, 1987

Before I found gay punk rock, or even subliminally homoerotic cartoons, I had Tasha Yar, chief of security on the Enterprise (and an androgynous female lead with a nebulous love life who co-parented with a Romulan and lost her life battling Armus the slime alien). Tasha helped me see myself — my rejection of softness. —Cristy C. Road, artist, graphic novelist, musician

Trash: Short Stories by Dorothy Allison, 1988

At a reading years ago, Dorothy Allison smiled in her knowing, southern way and said, “I’ma fuck you up.” I laughed, we all did, but underneath the breezy sentiment lay the startling truth: She does fuck you up—brutally, irrevocably, magnificently—and sometimes all those ways at once. She articulates our fears and desires in a voice so haunting and lustful it’s as if she were speaking in two or three languages. Plus, her use of eggplant as foreplay deserves an award. —Anna Pulley, author, The Lesbian Sex Haiku Book (With Cats) (forthcoming)

“Eau D’Bedroom Dancing” by Le Tigre, 1999

Bikini Kill’s lyrics introduced me to my first real doses of politically charged feminist ideology, but it was a Le Tigre song called “Eau D’ Bedroom Dancing” that got my mind thinking about queer love. I don’t think the song was even intended to be about sex; I think it’s more about the safety and privacy one feels when dancing alone in your room when no one’s looking. But something about its lush, moody melody awoke something in me that had me daydreaming about women in a way that I never had allowed myself to do before. —Signe Pierce, performance artist

Desert Hearts, 1985

This adaptation of Jane Rule’s novel was the first film to hit mainstream theaters directed by a lesbian (Donna Deitch), based on a novel written by a lesbian, with a lesbian-positive ending — which is to say neither woman died or went crazy or got punished or returned to men. Another distinguishing characteristic: We witness the younger woman painfully struggling with her mother figure over her sexuality in a frank, authentic way. —Kera Bolonik, executive editor, DAME Magazine

Medallion by Gluck, 1937

She called it her “YouWe” picture. Two profiled heads fused together, one dark, one fair. They stare into their future. I chanced on this painting in a Bond Street gallery and knew with a thrill what was going on. Here was the quest of my youth, what Carson McCullers called “the we of me.” I searched but found nothing in writing about Gluck’s life. She was invisible. So I wrote my first biography to find the facts: The profiles were Gluck and her lover Nesta Obermer. She was inspired to paint “YouWe” as they sat together at Glyndebourne on June, 23, 1936. Gluck felt Mozart’s Don Giovanni merged them into one and matched their love. “Darling Heart, we are not an affair are we—We are husband and wife,” she wrote to Nesta when she got home. —Diana Souhami, biographer, Gluck: Her Biography, The Trials of Radclyffe Hall, Mrs. Keppel and Her Daughter, and Natalie and Romaine

Je Tu Il Elle, Chantal Akerman, 1974

In 1985, my roommate, David Baer, and I went to see Je Tu Il Elle. The film was black and white, nearly silent. In one scene, two women create an oddly acrobatic, yet enticing, simulation of oral sex. “That looks like fun!” said David, a gay man. A few months later, riding his bike at 65th and Broadway, David was hit by a bus and died. In shock for around ten years, I rationalized the accident maybe preempted a painful AIDS death. Asked why we’re here, John Updike said, “We’re here to give praise.” Without David, without Chantal Akerman (because, clearly, images are bridges to experience), who would I be? —Jennie Livingston, filmmaker, Paris Is Burning and Earth Camp One (forthcoming)

DKNY advertisement, 1999

The first page of my teen diary is a DKNY ad for underwear featuring Esther Cañadas in men’s briefs, ripped out of an issue of Harper’s Bazaar. Long before queer and gender-fluid models like Cara Delevingne, Ruby Rose, or Casey Legler, this was the first time I’d seen a woman’s body in “men’s” clothing. Of course, looking back, this ad is for men, but at the time, it was for me. —Vanessa Haroutunian, filmmaker

The Lesbian Body by Monique Wittig, 1975 (English translation)

This book now looks unreadable, but at one time Wittig’s writing conveyed the essence of freedom, of unrestricted pleasure in language and sensuality — a wild, experimental, and defiant originality that remade a woman’s body and sexuality on its own terms, tearing down pronoun, nerve, and sinew. That’s what we needed, and we reveled in it. —Carole DeSanti, executive editor, Viking Penguin; novelist, The Unruly Passions of Eugénie R.

L’Avventura, 1960

I was lying on the floor in my sister’s room. It had rough gray carpet. The afternoon light was gray too, and it was raining. I was watching TV, and even though I find this hard to believe, I was watching Monica Vitti in L’Avventura. Maybe I’ve projected her into that TV set — maybe it was really Doris Day. But back then there weren’t too many opportunities for a kid to see Monica anywhere, and either this was or I remember it as my first purely sexual encounter. And that’s how I know it wasn’t Doris Day. —Roni Horn, visual artist

The Baby-Sitters Club by Ann M. Martin, starting 1986

I was obsessed with this series as a child. People always talk about the character Kristy being butch and a proto-lesbian. Even though they were, on the surface, straight stories, there was something about this group of girls hanging out every week in one friend’s bedroom that reminds me of queer collectives in my 20s. —Ariel Schrag, graphic novelist, author of Adam

“Herstory Inventory” by Ulrike Müller, 2014

At the Lesbian Herstory Archive in Park Slope, Müller came across an inventory list with detailed descriptions of feminist T-shirts from the archive’s collection. Müller invited 100 feminist artists to retranslate this list into drawings and motivate a collaborative rethinking of the lesbian archive and its visualization. What came of it was a true archive of a particular network of queer feminists and an inspiring read for every young lesbian. —Pati Hertling, independent curator

*A version of this article appears in the November 16, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.