Lou Reed once said something like, “Hip speaks in a pitch so high, only dogs can hear it.” That’s what I kept thinking as I made my way through more than 100 works by mostly contemporary artists in “Collected by Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner,” the Whitney’s new sixth-floor-filling show of super-stripped-down, quasi-conceptual, and otherwise super-hip austere art. Some of this art is excellent; some will be forgotten before the turn of the next decade, or sooner; about half of it is addressed only to deep art-world artists and insiders of a certain cerebral ilk who turned away from the world and inward to art during the darkness of the Bush years while being widely lauded as cool in the boom of the market. Because half of this show is so lacking in optical juice, by show’s end I was psychically dehydrated. For relief, I dove into the succulent color of Rachel Rose’s video and the kaleidoscopic insanity of the Frank Stella shows on the floor below.

I know the work of all the artists in the show, admire some of it, and grant that what’s on view is a sliver of a very defined, extraordinarily narrow generation that has helped to define art of that period. Good. But the exhibition as a whole is so tamped down, the only way to get traction was by standing next to works of art and reading long wall-labels that explain the important political, economic, and art-historical content that they purport to contain. (Each time someone recognized me, they came up to me, flummoxed, asking, “What is this stuff supposed to be about?”) In fact, with a group of fantastic exceptions, in reality, much of the work here has as its ultimate content both a familiarity of art about art, done in preapproved approaches and an unoriginality of either form, structure, touch, color, composition, surface, materials, or 100 other densities and intensities that make for originality.

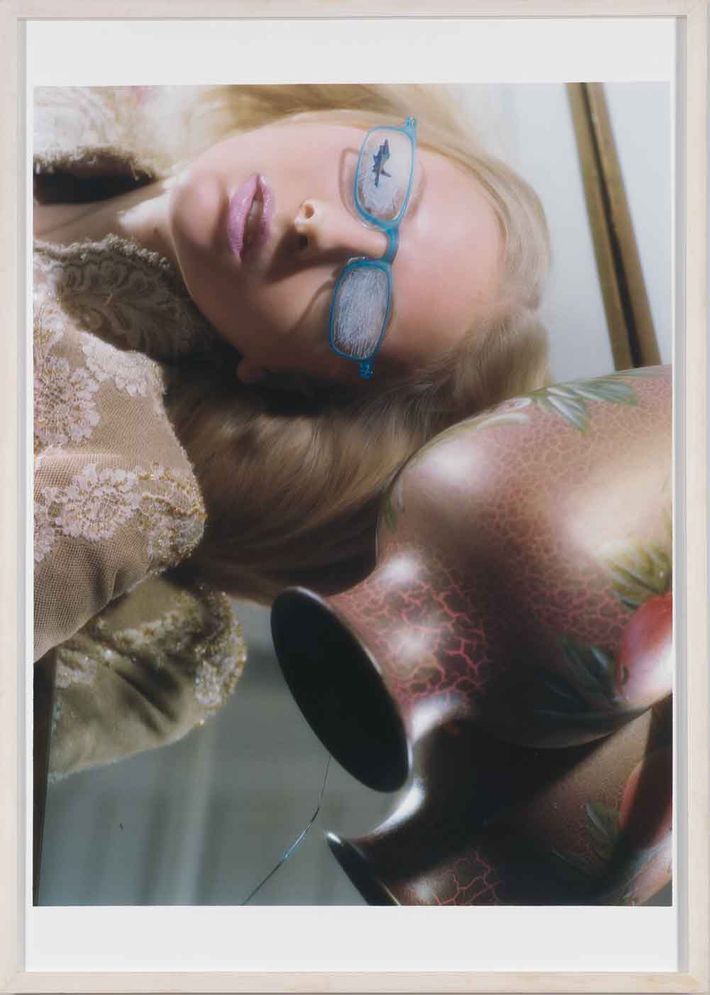

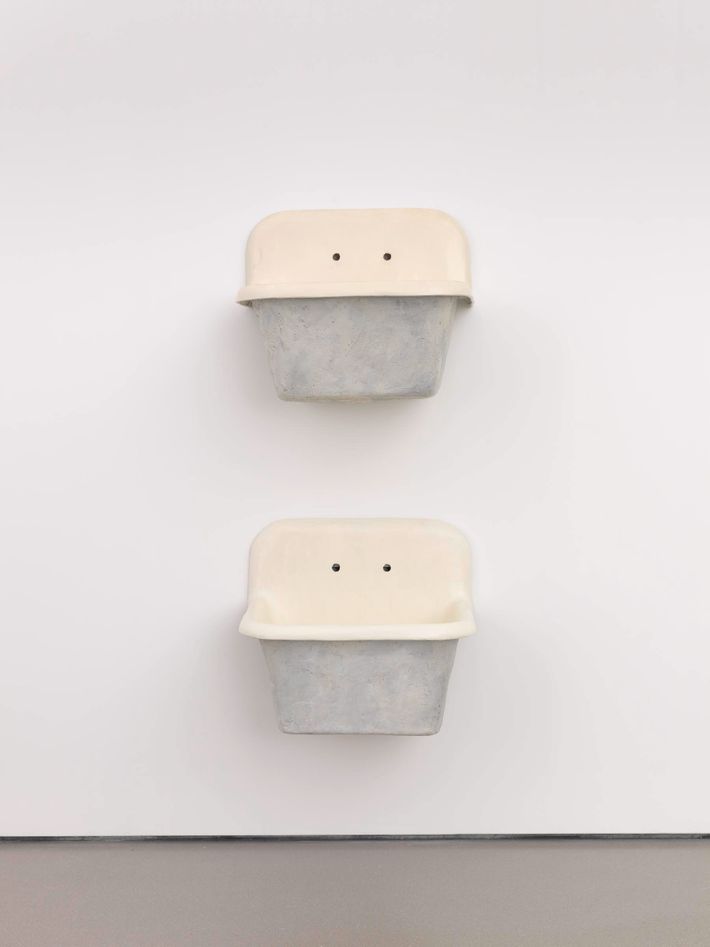

Among other early outstanding works on view is a great light piece by Dan Flavin — one from his famous Monument for V. Tatlin series from 1969 — and excellent photographs by Robert Adams, Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, Larry Clark, and Cindy Sherman, including five early Filmstills. Indeed, the ’80s come off the best here, with three good Gobers, especially the tremendous 1985 Ascending Sink, which reverberates with more inscrutable pathos than ever, handfuls of strong Richard Prince pictures, wonderful Sherrie Levine watercolors, and a few lesser-known Jeff Koons pieces. Plus, the additions of Anne Collier and Bernadette Corporation after that, and real-unreal-looking photos by Annette Kelm, and Laura Owens’s impressive flunky paintings, Alex Israel’s self-portrait painting-as-logo, and a number of Klara Liden pieces, including a handmade bench that rests on bundled cardboard boxes and doubles as a slide-projecting sculpture — all of these might lure viewers in for years to come. With exceptions, the other half of the show comes replete with the usual monochromes, explorations in abstract painting, Michael Krebber — of course — and, needless to say, a batch of quasi-abstract photography about, ta-da, photography, the kind academics can’t get enough of.

And yet there’s something wonderful in the offing. For art-world tea-leaf readers, the highest pitch emanating from “Collected by Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner” is that this exhibition is another step in the nifty palace-coup being carried out by this longtime “junior” member of the big museums, the Whitney making good on the great interior spaces it unveiled this spring, a signal that a major shift in the meta-museum landscape is already taking place.

Whatever you think of the taste on view, “Collected by Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner” is the tip of a massive gift of over 550 works given almost without condition to the Whitney by two great collectors. A half-dozen other shows could be culled from this collection without repeating a work. Looking at the total gift listed in the back of the show’s catalogue, many of those shows would be good. To say nothing of when this art is integrated into the Whitney’s collections, exhibited with other art, or loaned to other institutions. In other words, this collection is far greater than this show. It is among the largest caches of art ever given to this museum since its founding in 1931 by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who bestowed around 400 works to it. In a kismet of perfect timing, Westreich and Wagner have also donated 300 more works to the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

There’s more that makes this gift so notable. We’ve just lived through a period of “important” American collectors giving “important collections” to “important museums” like MoMA, the Met, Tate, and others. Rarely has the Whitney been the recipient of one of these big gifts. Especially in this international era, and with the Whitney having no space to exhibit its collections in its wonderful but cramped Breuer Building, and no conservation facilities to speak of to take care of it. During this same period, many collectors created their own museums where collections live in suspended isolation from all other art with viewers, never knowing if all this will one day be closed, sold off by heirs and siblings, or lost in divorces. Moreover, during this period, the vast majority of collectors, rather than giving art back to art and the art world via gifts like this, instead simply cashed out whole collections at mega-auctions, taking home boatloads of money. “Collected by Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner” is an augur of something hopeful — a gift that may lay tracks for other ways for collectors to think about their collections, institutions, and history. This is even more important in this time when museums can’t afford to collect contemporary art at all and instead must collect collectors to survive at all, when most museums’ annual acquisition budgets can’t even cover the price of, say, one Christopher Wool painting. “Collected by Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner” has three Wools, all excellent.

Before we look at the deeper implications of this gift, a few words about this married couple. In a time of art flippers and dick-wagging trophy hunters who buy art alphabetically, by numbers and big names, with no personal taste whatsoever, assembling cookie-cutter collections, and using art as a placeholder, Westreich and Wagner are from another planet; call it Old School. I know them both a bit; I have seen them in galleries, at openings, and in the art world for 30 years. Each had been a collector before they met in 1991 and married soon thereafter. He’d been a Democratic Party organizer in California and collected ceramics and outsider art (in fact, giving a great Bill Traylor drawing to MoMA). She moved from Washington, D.C., to New York in 1988 and started an art-advisory business. Before you think, Ohhh, I get it; they’re icky art advisers, these two aren’t those kinds of wheeler-dealers. Both are extremely opinionated, speak their minds, can argue most people — including me — under the table, have been way out in front of different curves, and have highly individual taste. If you’re still cynically thinking, Yeah, but they’re still just more rich people buying famous art, as much as I loathe reducing art to prices, they paid $50 for their first Cindy Sherman, $7,500 for their first Christopher Wool, and $5,600 for their first Jeff Koons, a vacuum-cleaner sculpture they saw in the same Maiden Lane studio I saw it in — and still regret not keeping the ballpoint-pen drawing of an inflatable bunny he drew for me during that visit. They buy early and in depth, and stop collecting an artist when the work becomes too expensive. (It’s always been a mystery to me why artists like these, who’ve been supported early and often, don’t just gift works regularly to the same collectors.)

On my own personal art-world thunder road: The first time I met Thea in 1989, I didn’t like her. At all. It’s a long story, but I was still a long-distance truck driver who’d somehow been asked to curate an exhibition in Italy of 1980s American art. All I recall now, other than that I never wanted to curate another show in my life, is that she was the most exacting lender that I’d ever met. Only later, when I actually got my foot in the art world, did I realize that every complaint she made was spot-on. In addition, the two have published books with artists, organized good shows with Richard Prince and Robert Gober, funded productions, helped artists, and all the rest.

Which brings us back to the deeper museological tectonics implied in this gift. Since the Whitney opened to such excellent effect, I’ve heard other high-level collectors talking seriously about not giving their collections to the other usual institutions. Particularly, I’m afraid, to MoMA, where this collection would fit perfectly into the super-conceptual tilt the museum has taken of late. Collectors now know that, with its cramped, unfriendly spaces for art, their collections would most likely end up in MoMA storage, and when the art is seen at all, it will be in MoMA’s current unfortunate conditions. MoMA is now desperately trying to correct that by building an entirely new $93 million structure. At the same time, the Met is moving into the Breuer Building and taking a position on modern and contemporary art. This show, at this museum, at this shifting moment, is a signal to many collectors that the game has changed.

That’s great for everyone. This shift from the absolute hegemony of MoMA and the out-of-it-ness of the Met is the best thing to happen to all our museums. “Collected by Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner” finds the Whitney finally, after all these years of second-class citizenry or otherwise making a mess of things, all but equal among its peers, equal in intention, exhibitions, scholarship, and now, with this gift, in the art of the 21st century. This is tremendous, arid exhibition aside.