Tillie Walden’s first comic was about her paternal grandmother, who died before Walden was born, and who is her namesake. The late Tillie was an artist, too, and her paintings hang in Walden’s childhood home. “I made a simple black-and-white comic about never knowing her but following in her footsteps, and when I showed it to my dad, he cried,” she said. That was when she realized she could make people feel something with her art.

It was her dad who talked her into putting comics and drawings on her website, which is how Avery Hill Publishing discovered her work. The British publisher emailed her while she was still in high school asking if she’d like to work with them. She panicked (“I thought it was a scam”), told them she had too much to do senior year, and to get back to her after she’d graduated. To her amazement, they did, and her first graphic novel, The End of Summer, was the result.

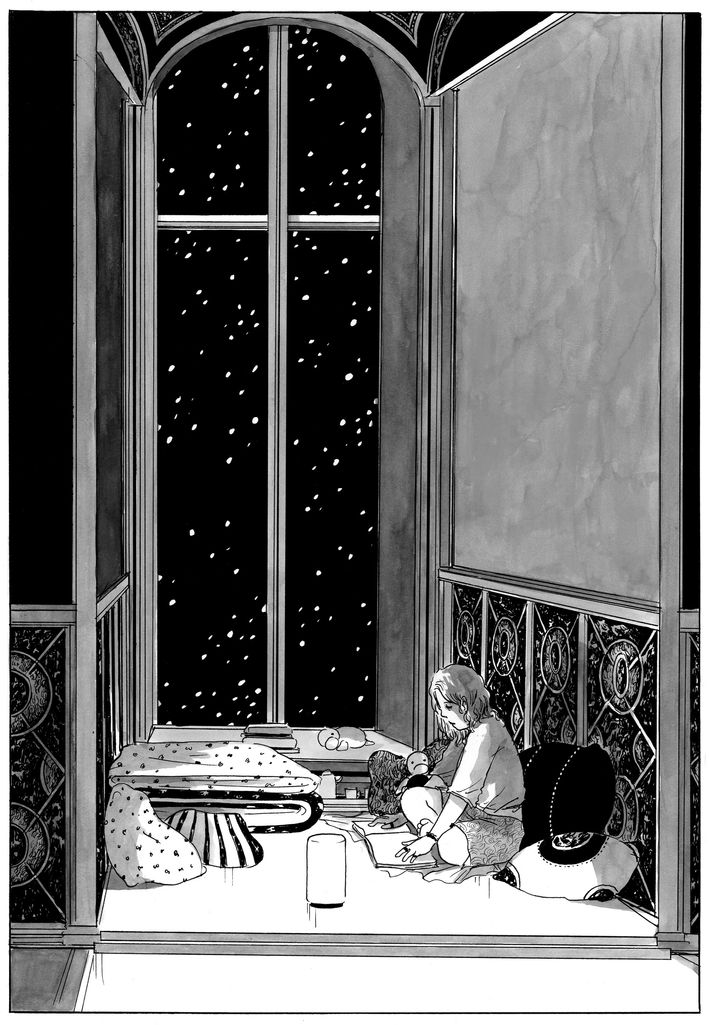

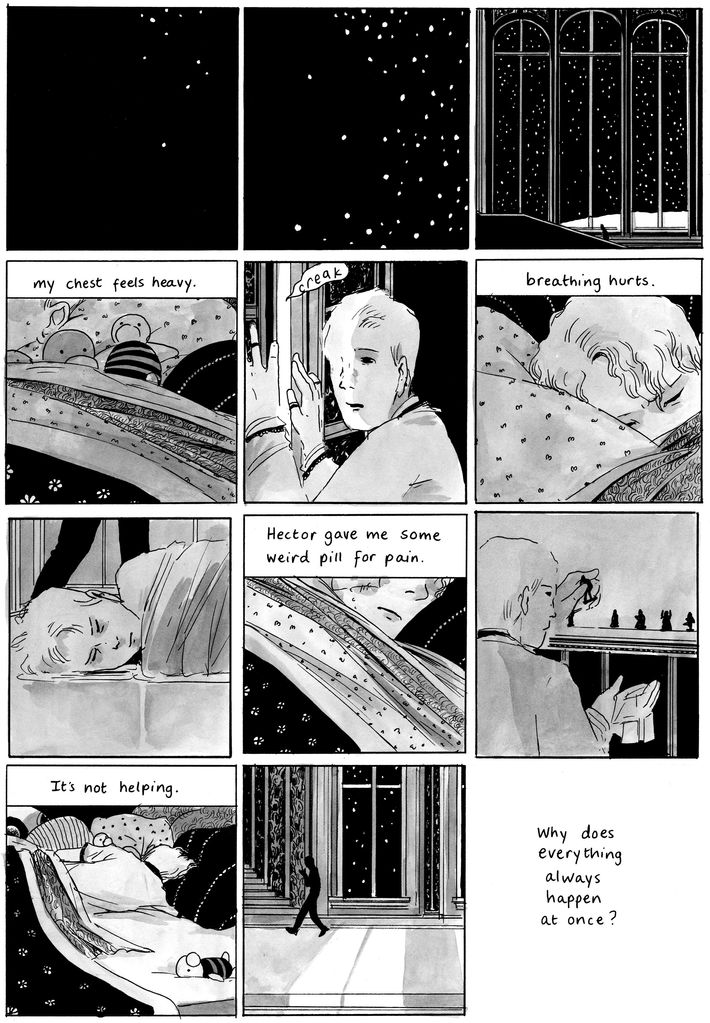

That book is told from the perspective of Lars, a sickly boy who rides around on a giant cat named Nemo. He and his family live in a fantastical palace that’s about to shut its doors for a three-year winter. As the icy season progresses, tensions in the family rise and story lines become increasingly twisted — Lars has to deal with Maja, his headstrong twin sister who’s beginning to rebel against family norms; their older brother’s manic tendencies escalate; there’s at least one scandalous romance; and their mother tries to hold everything together. Tragedy and discomfort permeate The End of Summer, but it’s a beautifully told story nonetheless.

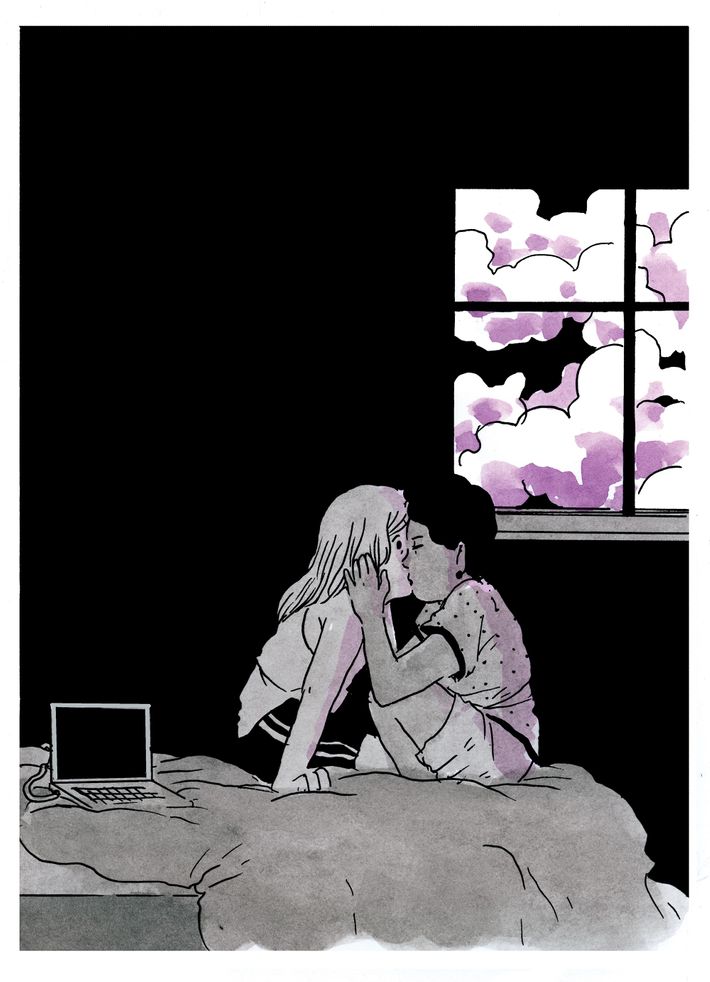

Almost immediately after The End of Summer was released in June, Walden started work on her second book, I Love This Part, which was released by Avery Hill on November 14. It’s another gut-wrenching story — this time about two teenage girls who bond over movies, music, and the internet, and in the process innocently fall in love. We caught up with Walden to talk about her creative process and the real-life events that inspired I Love This Part.

You’re about to graduate from the Center for Cartoon Studies; you’re working on your thesis, which is a graphic novel; you already published one book while in school, and now there’s I Love This Part. How do you get so much done?

I have to get ten hours of sleep every night — I refuse to ever let comics interrupt my sleep. I go to bed at 8 p.m. every night like an old lady. But I’m also at the point where I don’t struggle with drawing at all, so as long as ideas are flowing and I’m working on something interesting, I can draw anything. I’m also not afraid to make pages and get rid of them. When I was younger, I thought the pages I made had to be the perfect reflection of my vision, but now I know things don’t work like that. I just made 50 pages of my thesis, and I’ll use maybe 30, but making 20 bad pages is still good because I’m still being productive.

So you’re not exactly a night owl?

No. I do my best work early in the morning. I like to wake up and just go straight from being asleep to sitting at my desk. I like that my work has this sort of sleepy, dreamy quality to it, and I think a lot of that is because I’m actually sleepy and dreamy as I’m making it.

Are there any artists whose work particularly inspired you?

Sam Alden is an indie cartoonist, and I read his comics online. He makes really dreamy, cool stories. My style is very similar to his because I started trying to draw like him.

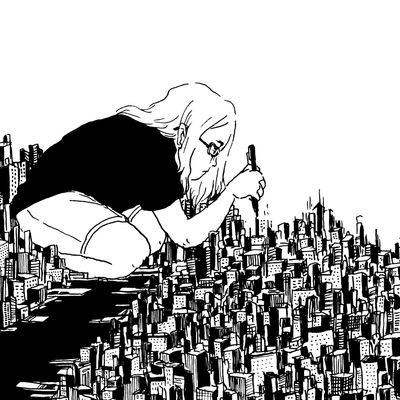

You have some incredible settings in your comics: outer space, miniature cities, mazelike palaces, and jungles, to name a few. What inspires that?

I like backgrounds because I like making stories where it feels like you have to go somewhere, and backgrounds are usually the way to do that. In big spaces, or in spaces where you can see partially down a hallway or slightly around a tree, there’s always potential for something to come around it or for a story to happen.

How did you come up with the idea for The End of Summer?

It was winter break, I was home in Texas, and I’d been talking to the team at Avery Hill. I told them I had an idea for a book and they were like, ‘Cool, send it to us!’ And I was like, Wait, I don’t actually have an idea for a book. I lied! When I write and draw, I have to be covered in blankets and pillows, so I immersed myself in bed just like Lars. I ended up writing and drawing Lars and Maja and the cat over and over and over again, so I thought, okay, they’re in this huge place. If I were in this place, what would I do? Then I hopped out of bed, jumped in the bath, closed my eyes, and thought, what can go wrong? I jumped out of the bath and wrote it all down, and it still made no sense, so I got back in the bath and got back out and kept doing that until I had a story with edges to it. Once I get myself going, I can’t stop until I’ve figured everything out.

That’s one way to do it.

I don’t spend a long time thinking about doing it differently. I’m really about going with your gut feeling.

A huge part of the book is autobiographical, right?

Right. My strongest stories come when I put part of myself and my experience in them. For instance, I was always really sick as a kid, and in 11th grade I started having heart issues and breathing issues and was in and out of hospital for a little while. It was one of the lowest points of my life — I couldn’t bear to think about all the school I was missing, and I couldn’t bear to think about what was going on with my body, so I just lay there and dreamily thought of stories and places and tried to take myself anywhere but the hospital. So Lars’s issues in The End of Summer came from a very emotionally and physically real place, and doing that book actually helped me close off that part of my life. When I draw a character going through something that I went through, it makes me feel weirdly less alone, and it helps me make it a lighter subject — it becomes less of an experience that I had and more of a magical thing.

Is I Love This Part autobiographical to the extent that The End of Summer is?

Yes. When I came up with the idea for the book, I was getting very nostalgic for a relationship I had with a girl in middle school, and remembering the dumb things we said to each other. I’m not in touch with that girl anymore because it ended badly — her mother found out and didn’t want a gay daughter. We were both closeted at the time, so it was all very secretive.

What was it like to draw queer characters now that you’re out of the closet?

I don’t think I could’ve drawn a graphic novel about two young lesbians if I wasn’t out right now. I always avoided the whole queer thing in stories because I felt like I couldn’t draw openly gay characters if I was still scared to be openly gay — in The End of Summer there’s a gay character, but it’s very quiet and hidden and shadowy. Now a huge part of my voice is the fact that I’m gay and I like writing gay characters. It was so nice to draw girls kissing!

A lot of your comics are mean to inspire an emotional response. When you’re working, how can you tell if you’re getting that right?

The stories that naturally come into my head are pretty emotionally big, but the moments I choose to show in a comic and the way I make it is intended to evoke a response. The way I gauge if I’m doing it right is: I sit, close my eyes, grab my stomach, and imagine the whole story in my head. If I have a reaction in my gut, if I feel something, then that’s it. There’s something cool about being able to put pictures in boxes and make someone feel something.