In the last few decades, the dozens of companies that once made up America’s publishing industry — Viking and Doubleday, Anchor and Crown, Dutton and Ballantine, and the rest — have grouped into just five multi-billion-dollar conglomerates, sharing offices at a few towers within a six-mile stretch of Manhattan. But that’s also freed up space at the other end of the spectrum, as scores of tiny independent publishers have arisen to fill the vacuum: from Dalkey Archive Press, which specializes in translated and postmodern literary fiction, to Verso, the predominant publisher of America’s political left, to poetry presses like Bloodaxe Books.

Perhaps the smallest among them is ANTIBOOKCLUB, the operation of 33-year-old Gabriel Levinson, which releases just one title of literary fiction or nonfiction each year. Levinson, who lives in Williamsburg, handles every task himself, from editing to marketing to bookkeeping — and funds the business expenses with credit cards and the paychecks from his day job as an associate editor at Abrams Books. And since last year, he has sold off almost his entire personal library, amounting to some 2,500 books, including many of those he held dearest, such as first printings of Nelson Algren and Charles Portis novels, to free up space on a credit card to pay for galleys of his next gamble, a 1.6-pound coffee-table collection of the letters of Terry Southern, Yours in Haste and Adoration. (It features correspondence with Kubrick as Southern was writing the screenplay for Dr. Strangelove and with Dennis Hopper as he wrote Easy Rider; and spans his early reporting forays, including the 1962 Esquire essay that Tom Wolfe credited with launching the New Journalism movement, and his work on the early Saturday Night Live.) “It was crushing,” Levinson said in a recent interview about cleaning out his own library. “But I’m reconciled with it. I do believe that. I believe that it’s for the greater good.” “It stops you dead in your tracks when you hear what he’s up to,” said literary agent Bill Contardi, who recently sold Levinson a fiction manuscript. “He’s adventurous, but he’s realistic.”

Levinson first made a name for himself in Chicago, where, in 2007, while working as an editor at Make magazine, he bought a customized cargo bike and filled it with books donated from publishers. Every weekend he rode to public parks and gave the books away, in armloads, to anyone who approached him. After he started receiving national press — in The New Yorker, among other venues — “book bikes” began cropping up in other cities, following his model. “There are more book bikes in existence today than I can track,” he said. “My name is no longer associated with it, which I think is badass.”

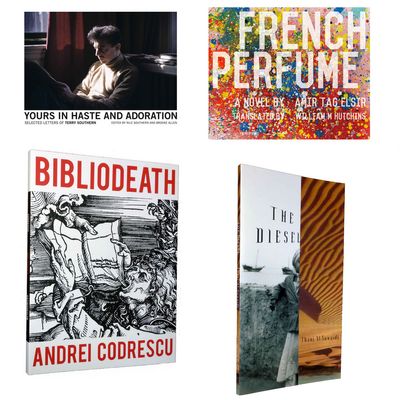

Around 2010, he sold off his immense record collection and took out a loan to publish his first book: A Brief History of Authoterrorism, a collection of short stories concerning the supposed death of print. He moved to New York early last year, and more titles followed: the novels The Diesel and French Perfume, both translated from Arabic; Bibliodeath, a memoir by the Romanian poet Andrei Codrescu; and The End of the World, a graphic novel by the animator Don Hertzfeldt. Along the way, he began working with the distributor Independent Publishers Group to expand his reach. But after several years, he decided this arrangement was hurting more than it helped.

Whenever bookstores wanted to return unsold titles, Levinson was obligated to give them cash refunds — which sometimes put his authors’ monthly statements in the red. He said this model depends on the publisher releasing at least a dozen titles a year. “The only way you can make these returns not hurt you is by churning out book after book after book.” He met with several other distributors to ask whether they’d negotiate by letting him offer credit refunds instead, but none of them would budge. To make matters worse, he couldn’t work with stores directly to figure out why the titles weren’t selling: Misguided marketing campaigns? Poor placement on the shelves?

This time, with the Southern collection, he’s decided he can’t afford to work with a distributor, and he’s asking bookstores to take a chance by purchasing books from him directly. And as of this month, his titles are available at the Strand, McNally Jackson, and Amazon, with more agreements in the works. “It’s a one-store-at-a-time situation,” he said. “Once I conquer New York, which is my goal, then Politics and Prose (in Washington, D.C.) will be next.”

On the other hand, he said, his pace is unsustainable. “I have lost money on everything I’ve done.” For Codrescu’s memoir, he ordered 5,000 copies to be printed, his largest print run to date, thinking they’d sell quickly on account of the author’s reputation. But he ended up with leftovers, which put him farther into the red. So now, with the Southern book, he’s trying a different tack: He ordered just 500 copies, and he if he sells the 450 or so that aren’t bound for agents and book reviewers, he’ll break even and be ready for a second printing. Smaller press runs cost more per copy, which is one reason he needs to scale up dramatically: hiring more staff, increasing his output. “Every day, I have no damn clue what I’m doing, and that’s kind of the fun of it,” he said. “I fall hard with every single book, but I’ve never fallen the same way twice. Every mistake I’ve made becomes a red flag.”