It’s hard to summarize any of Diane Williams’s stories, and it may be beside the point. But let’s try. “Greed” opens with mention of an inheritance from the narrator’s paternal grandmother: “a pile of jewels.” It’s claimed by her father, so her mother comes into possession of two gem-set rings that late in life she “amalgamated” into one: “the diamonds and the sapphires were impressively bulked together.” It’s a striking image; the narrator calls it a “phantasmagoria” and says she wanted the hybrid ring to be a reminder of her mother. Then comes the story’s last line: “It’s hard to believe that our affair was so long ago.” I’ve made an assumption here that could be incorrect: that the narrator is female. We don’t know, and we don’t know who the other half of that our is, and what the jewelry, or just the amalgamated rings, had to do with the affair. And that title — who is the greedy one? The father? The narrator? The narrator’s lover?

This effect — opening up the story’s meaning in a single line — is perhaps a move more often found in poetry than in prose fiction. But to say that Williams is a poet who happens to write prose won’t quite do. Although there are affinities with postwar American poetry, Williams is working consciously, I think, against the grain of the conventions of fiction. Her stories tend to veer away from any expectations put forward in the first few lines. There are apparent disjunctions, jarring juxtapositions, and seeming non sequiturs. Language often seems to be calling attention to itself and away from the narrative flow. But these turns often resolve into texts with their own sort of coherence — of a sort that’s neither vacuum-sealed nor merely morally ambiguous in the ways we’ve been trained to read fiction. No epiphanies or plots, but vectors of life. Because they seem so far removed from something that might be documentary, the strangest sensation is the suspicion that they might simply have been ripped from autobiographical material and then transformed, as if through photographic exposure or audio distortion. (There are narrators who turn out to be named Diane; a narrator’s mother called Mrs. Williams; a few male names pop up multiple times, suggesting connections between stories or between the stories and life — but all of these could be false leads.)

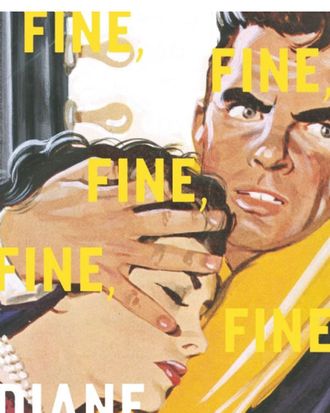

Williams’s new book, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine — her eighth — collects 40 stories. These are miniature fictions, the shortest just three sentences in five lines, and the longest five pages. The most obvious pleasure of Williams’s writing is her wit — always deadpan (“His face is not difficult to explain—it’s cathedral-like”), occasionally impish (one character is nicknamed Imp), often quite mordant (the last line of a story about a marriage: “And after the last years were over, we were dead”), and not infrequently perverse (the start of “Head of a Naked Girl” explains how men the narrator has known got their erections). Williams is not averse to the arresting opening line. Here are a few:

“People often wait a long time and then, like me, suddenly they’re back in the news with a changed appearance.”

“On the avenue, I was unavoidably stuck inside of an uproar when the wind locked itself in front of my face.”

“Why would anyone be fearful that the man might become distressed or that he might lose his temper in their bedroom?”

“She had stopped insisting that they have heart to heart conversations, but for stranded people, they had these nice moments together, and he had his professional enjoyment at the newspaper.”

All of those sentences nicely captures Williams’s estranging way with everyday language. Then there are her sparing similes. There’s that “cathedral-like” face; a woman’s misfortunes are “like the common corncockle flowers on the fabric of my wing chairs”; the lines of age are drawn on a narrator’s face like “marks made by a claw”; a cup of tea has “the tang of the dirty lake of her childhood that she remembered swallowing large amounts of while swimming.” Occasionally Williams will launch into something like a parody of a familiar form of storytelling. Imagine a 19th-century novel that begins like her “Head of the Big Man”:

The family was blessed with more self-confidence than most of us have and with a great lawn, with arbors and beds of flowers, and with a fountain in the shape of a sun at the south end. It is not our purpose to say anything imprecise about their scheme, how they had gotten on with tufted and fringed furniture, with their little tables, a parquet floor, a bean pot.

The walls inside of this country house were amber-colored where they entertained quite formally—until the old mansion was destroyed.

Yet this isn’t a parody but a story about aging told in an instant, about a pair of “morally strong, intelligent people who were then spent.” From the first view of the house it moves through a couple’s life in a quick montage, until their house becomes a tourist trap for visitors who can’t imagine its former inhabitants beyond the thought “Looks like one of you splurged!” More than Williams’s language calls attention to itself, which it does; it puts the reader in mind of other stories, other scenes, other books. Her work activates the memory of language and its mutations across time.

Comparisons aren’t very useful with Williams, but a couple are inevitable. Her veerings do have a lot in common with John Ashbery’s work from the late 1960s and early 1970s, as do the spirit of her titles, with their offhand beauty and their flirtations with whimsy. Note the shifts in register at the end of Williams’s “Palm Against Palm”:

The brightly scaled moon was rising, but this girl never became a well-liked businesswoman with a growing family in the community.

Neither is she endowed with any remarkable qualities. We never spoke of her specialized skills or her inclination to be otherwise. My fault. Go fuck herself.

Apology accepted.

And of course there’s Lydia Davis, who also works in miniatures and whose writing appears regularly in Noon, the magazine Williams has edited since 2000, as does the work of Gary Lutz, who arguably pursues similar estrangements at the sentence level. But putting any of these gnomic writers side by side only points up their differences: Davis’s tendency to recursive self-questioning; Lutz’s focus on diction as the means of estrangement. The avant-garde Williams assembles in her magazine is an eclectic one that cuts across a few generations. (Many of its contributors also found their way into Ben Marcus’s recent anthology New American Stories.)

There’s no shortage of death in the pages of Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine — a fatal car crash, a fatal cycle crash, a drowning, a ghost story, etc. — as well as strained and frayed marriages, love affairs, relations between parent and child, tense dealings between strangers. Though Williams eschews psychologizing and we only see her characters in flashes and hear their voices in a handful of sentences at most, there is a cumulative power across the book; a unifying spirit that’s desperate at times but never despairing, and once in a while joyous, even exuberant, like a veil lifted up to reveal an exclamation point.