Spoilers ahead.

If the last couple of years in American popular culture have taught us anything, it’s to thank the lord for every day you aren’t ensnared in our criminal-justice system. As episodes five through seven of Making a Murderer show, cops and judges don’t have to be malicious to do you wrong, and even ace defense attorneys Dean Strang and Jerry Buting — who are the legal equivalent of Ferris Bueller and Cameron Frye, respectively — can only do so much on your behalf.

In episode five, the representatives of the state complain to the judge that they are “swimming upstream,” or that they will be if the judge agrees to the defense’s suggestion that he give “curative instruction” to the jury. The defense points out that the jury has been exposed, via incessant media coverage, to salacious details about the case, including the allegation that Steven Avery raped and tortured Teresa Halbach before killing her, which the prosecution will not actually bring up, or bother to prove, during the trial itself.

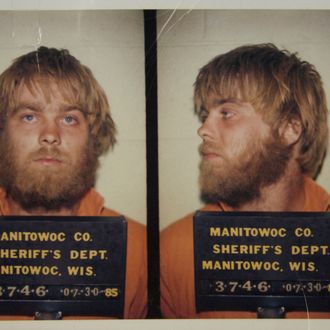

The judge declines to give any special instructions to the jury, in the same manner he declines virtually all of the requests of the defense. The prosecution, in response, drops two of the charges that it had tacked on after taking into account Brendan Dassey’s confused, contradictory “confession,” and the trial of Steven Avery — on four counts, including murder — begins.

What follows is six weeks of trial condensed into a few hours of television, during which the state presents its evidence and the defense picks it apart. There are Halbach’s cell-phone records to pore over, her bone fragments to examine, and the splashes of blood to test for any indication that they came from a test tube rather than from Avery himself. There are also witnesses of a sort, people — including Brendan’s brother Bobby — who claim some connection to the property either during or after the time at which the crime is supposed to have taken place.

Everyone’s memory is faulty in some way, as is every piece of evidence. With only closing statements left to make, the defense feels cautiously optimistic that it should be able to leave the members of the jury with reasonable doubt as to Avery’s guilt.

A lot was packed into these three episodes. What was left out?

The defense maintains it was odd that the police never followed any other leads or treated any of the men in Halbach’s life as suspects. They’re right.

Women are much more likely than men to be hurt or killed by people they know. In more than one out of every three cases, and more than 40 percent in some states, the murderer of a woman turns out to be a “male intimate partner,” meaning a current or former lover. Additionally, more than half of those women who are murdered by intimate partners are shot to death, as it appears Halbach was.

Starting an investigation into the shooting death of a 20-something woman by interrogating current and former boyfriends would seem to be standard practice. And yet Halbach’s ex-boyfriend, who admitted on the stand to knowing Halbach’s voice-mail password and who may well have deleted some messages from her mailbox, was never treated as a suspect. Neither was Halbach’s (male) roommate, who only reported her missing after she had been gone for three days; her brother, who claimed to be mourning his sister before her body was even found; or any of the other men in her life.

Other possible suspects, who go more or less unmentioned by the documentary, include members of the extended Avery family.

As journalist and private investigator Ann Brocklehurst points out, “The [defense] lawyers’ list of suspects was dominated by members of the Avery clan,” including Steven Avery’s brother-in-law, Scott Tadych, Charles and Earl Avery, and the Dassey brothers. Investigator Michael O’Kelly, who helped Brendan Dassey implicate himself in the crime, is on record as believing that “Avery’s brothers ‘could have had a role’ in Halbach’s murder.”

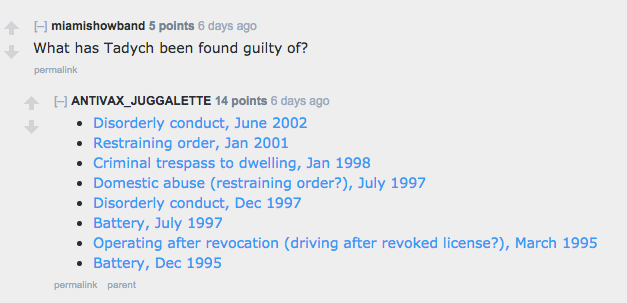

Tadych, meanwhile, has a documented history of violent behavior against women, and he and his stepson Bobby serve as alibis for each other on October 31. Various amateur detectives on Reddit have been putting together cases against all of these individuals, as well as others.

Judge Fox’s behavior, in continually siding with the prosecution, is not unusual. And what appear to be missteps from the prosecution aren’t unusual either. Neither judges nor prosecutors are ordinarily held accountable for their actions, however objectionable.

In a blistering piece on the blog Above the Law, a lifetime criminal-defense attorney asserts that “judges and prosecutors don’t care if they’re right” and calls our court system “broken.” According to the Center for Prosecutor Integrity, “an estimated 43% of wrongful convictions arise from misconduct involving prosecutors and other officials.” And Americans in general are concerned: “Over two-fifths (42.8%) of the respondents say prosecutorial misconduct is widespread.” DailyKos reports that “nine studies have looked at misconduct over 50 years, on both state and national levels, and found 3,625 instances. Of those, public sanctions were imposed in 63 cases, less than 2 percent of the time.” The sanctions, when they were imposed, were mild.

District Attorney Ken Kratz insists that some incriminating evidence was omitted by the documentarians.

In an interview with Maxim magazine, Kratz maintains that Avery’s DNA “from his sweaty hands” also connected him to Halbach’s vehicle: “Do the cops also have a vial of his sweat that they are carrying around? The evidence conclusively shows that Steven Avery’s hand was under the hood when he insists he never touched her car.”

Kratz also says that some of Halbach’s personal possessions, including her cell phone and camera, were burned in a barrel on Avery’s property, and that “two people saw him putting that stuff in there. This isn’t contested. It was all presented as evidence at the jury trial, and the documentary people don’t tell you that.”

He also claims that Avery boasted while in prison of his plans to “torture and rape and murder young women” once he was free. Though the judge did not allow that evidence to go the jury, the fact that the judge considered it may help explain his apparent antipathy to, and fear of, Avery.

EDTA tests are indeed both rare and unreliable.

EDTA, or ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid, is a chemical preservative. The FBI performed a rush EDTA test on the blood found in Halbach’s car in order to report, in support of the state, that there is no indication that the blood came from the vial of Avery’s previously collected blood (which itself was tested and found to contain EDTA) rather than from a free-flowing source (Avery himself).

A lawyer on Reddit voiced his disgust: “FBI test can produce false negatives on EDTA, which is why labs stopped using the test. Shameful that the judge let them use that test.”

The O.J. Simpson case is another high-profile situation in which the defense used a sloppy crime-scene investigation to accuse the officers involved of incompetence, if not conspiracy. An article from the Green Bay Press-Gazette at the time of the Avery trial quotes the defense bringing up that case — the last time the FBI performed an EDTA test in a hurry — arguing that the lab notoriously “screwed up” in that instance and, presumably for that reason, had not been called to testify in a trial since:

“In the last 10 years, nobody has come to your lab and asked for your lab to give us the benefit of your knowledge and your ability to test for EDTA in bloodstains, isn’t that right?” Buting asked.

“It hasn’t happened to me personally or to my knowledge,” LeBeau said.

“That might be because your lab screwed up in the O.J. Simpson case,” Buting said.

“No. We did not screw up, as you say, in the O.J. Simpson case,” LeBeau responded.

Buting pointed out that FBI tests found EDTA in a bloodstain on a sock and the defense used that evidence to help acquit Simpson of charges that he killed his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson, and her friend, Ron Goldman.

“I didn’t do the testing in the O.J. case and I’m not fully aware of all the final findings in that particular case,” LeBeau said. “I believe it’s been 12 years, but it’s my recollection that we didn’t report there was a significant amount of EDTA in that bloodstain.”

Cops have been caught, and even convicted of, planting evidence.

Leaving aside the O.J. Simpson trial, it is documented that police have planted incriminating evidence on defendants in various cases ranging from drug crimes across Alabama, in which thousands of African-Americans were framed over the course of a decade, to myriad other cases in Philadelphia, Camden, Detroit, Illinois, New York, and more. American servicemen in Iraq and Afghanistan have been convicted of doing the same.