Each month, Boris Kachka offers nonfiction and fiction book recommendations. You should read as many of them as possible.

The Queen of the Night, by Alexander Chee (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Feb. 2)

It’s been 15 years since Chee published his first novel, Edinburgh, a slim and powerful debut about a traumatic coming of age. He manages to both meet and defy the inevitable expectations with a grand, heavily accessorized historical epic. Queen is as operatic as its shape-shifting narrator, a professional “tragic soprano” (and former circus performer turned prostitute) chasing glory in the ashes of France’s Second Empire — until her secret past resurfaces to threaten her freedom and maybe her life. No self-conscious pastiche, this is classical, full-throated melodrama, not so much a meditation as an aria on fate.

A Doubter’s Almanac, by Ethan Canin (Random House, Feb. 16)

Forgive the plug of a second 500-pager, but there’s no better month for long nights with heavy books. Canin’s fifth novel ranges over two linked narratives — one about a mathematical genius who cracks a famous theorem at 32, the other about his equally talented son, who cracks the market at 20 and becomes a hedge-fund billionaire. Patriarch Milo is imperious and self-destructive, while the cannier Hans spends his life trying not to be. Alternately explosive and deeply interior, Almanac is more Buddenbrooks than A Beautiful Mind, but ultimately more hopeful than both.

In Other Words, by Jhumpa Lahiri, trans. Ann Goldstein (Knopf, Feb. 9)

A writer of controlled, lapidary prose takes a risk that pays off, like much of her work, in the telling. Raised by Bengali immigrants, Lahiri decides to throw off the chains of her family’s heritage and her adopted America by writing a book about moving to Rome and learning Italian — in Italian. (Pages alternate between Lahiri’s original and an English rendering by Elena Ferrante’s translator.) Lahiri both describes and demonstrates an expat’s push-pull of immersion and alienation, a process through which a novelist known for lyricism is refreshingly reduced to stark simplicity.

My Father, the Pornographer, by Chris Offutt (Atria, Feb. 9)

The least titillating book you’ll ever read about porn, and possibly the most interesting, Offutt’s memoir about his father’s secret occupation — writing 400 lurid paperbacks under 17 pseudonyms, initially to pay for Chris’s orthodontia — is as candid and methodical as Andrew Offutt’s assembly line of bondage fantasias. The family’s backwoods Kentucky home, dominated by a man who told his son that porn saved him from becoming a serial killer, could easily be painted in Gothic black, but Offutt tells the story straight, a loving if unsparing tribute to a very complicated father.

Forty Rooms, by Olga Grushin (Putnam, Feb. 16)

A young female poet, shedding Soviet Moscow for an American education, wants only “to live in a timeless poem.” But time catches up to her with brutal stealth, and before too long she’s “Mrs. Caldwell,” a wealthy suburban housewife without a stanza to show for it. Grushin, the Russian-American author of the extraordinary Dream Life of Sukhanov, spins a Bovary plot into a mystical tapestry, complete with ghostly harbingers, jarring shifts in perspective, and linguistic fillips most native-born writers would envy. She also crafts a feminist response to Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus — an artist navigating life backwards in heels.

Master of Ceremonies: A Memoir, by Joel Grey (Flatiron, Feb. 16)

The star who originated the role of Cabaret’s louche emcee tells his story, which is the story of the 20th-century stage, with style and candor. Grey first thought of the emcee role as merely a “metaphor”; it also became an uncomfortable reminder of the actor’s secret gayness. Grey obscured his Jewish upbringing by changing his name and his nose, but he could never lop off his desire, wife and kids notwithstanding. It took a star turn in Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart to launch him out of the closet, and 80-plus years to find comfort in his skin.

Strange Gods: A Secular History of Conversion, by Susan Jacoby (Pantheon, Feb, 16)

Neither a scathing New Atheist tract nor a dry academic history, Jacoby’s sweeping account of religious conversion, from Augustine to Muhammad Ali to the horrors of medieval Spain and modern-day Raqqa, finds an essential new angle of approach. An ardent secularist but a child of multiple American converts, Jacoby chooses to focus not on spiritual or psychological motives but on the social forces that drive religious change. Strange Gods may be off-putting to believers, but it’s a likely story and, in her hands, a lively one.

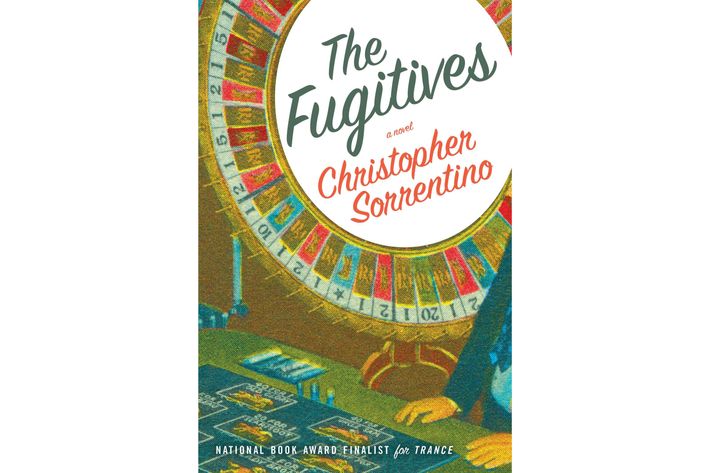

The Fugitives, by Christopher Sorrentino (Simon & Schuster, Feb. 9)

A novel about a literary novelist is a risky thing, especially if, like this one, it’s partly inspired by the author’s real-life scandal. Luckily, Sorrentino’s exiled writer — prickly, crass Sandy Mulligan — flees not just Brooklyn but its parochial mores, removing us to small-town Michigan and a Native American casino-mob caper that’s also about the traps of identity. To be sure, there’s room to spare for witty rants, humiliating raunch, and a sharp-tongued literary agent riffing on the death of publishing — all to the better.