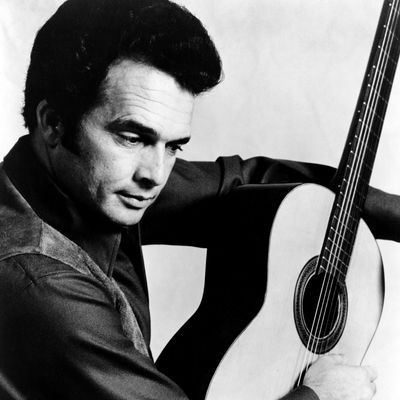

Merle Haggard was so talented he could float through a half-dozen genres (and generations) of country music and somehow always retain the respect of virtually all of his fellows. He disdained Nashville from his home in Bakersfield, and confounded even the outlaws with his sometimes cantankerously retro politics. But with his redolent baritone, implacable mien, and adherence to the country verities of twanging steady, singing true, and getting into a fistfight now and again, he embodied the music’s most fluid and authentic strains for a good two decades before his talents began to wane. Along the way he wrote and sang at least two timeless classics — “Mama Tried” and “Sing Me Back Home” — that rank with the best songs the genre produced, and his partisans will cite a half-dozen more. Haggard died today, on his 79th birthday, from complications from pneumonia, his agent announced.

Johnny Cash is a country icon often thought to have done hard time. (In fact, his brushes with the law were tangential.) Haggard, by contrast, grew up living in a converted railroad boxcar, lost his father young, and spent most of his teen years in and out of reformatories. As one of his best songs put it, “I turned 21 in prison”; he was in San Quentin. Finally ending up playing bass in a country band, he found ambition and went out on his own.

In 1965, he formed his backing band, the Strangers. Anchoring it was guitarist Roy Nichols, a guitar legend even in a genre full of them. (Haggard could play guitar and fiddle like an ace as well.) The Strangers became a subtle but still crack ensemble, able to rumble, stroll, and, now and again, rock a little through the tunes Haggard himself wrote or found from among his bandmates and other well-known songwriters. The country audience stays with its stars a lot more loyally than the pop or rock audience does, but even so, Haggard’s string of nearly 40 No. 1 country hits over two decades is impressive.

Haggard mastered the rueful love plaint (“I Started Loving You Again”), the rockabilly rumbler (“Workin’ Man’s Blues”), the alcoholic lament ("The Bottle Let Me Down”), the philosophical rumination ("If We Make It Through December”), even the socially conscious ballad ("Hungry Eyes”). His band could sail through just about any cross of country and other genres, even jazz, but always stayed true to the crisp and sturdy so-called Bakersfield Sound pioneered by it and (the much older) Buck Owens and the Buckaroos. (Haggard’s second wife was one of Owens’s exes; they wrote “I Started Loving You Again,” one of his most remembered songs, together.)

Several times in his career he struck upon something timeless. In “Mama Tried,” he makes a run at the old “here I am in prison” cliché. But drawing from his own experience of losing a father, running away as a teen, and riding the rails, he finds poetry and fate. The song’s rousing chorus and crisp delivery disguise the poignancy in the setup and the regret of its timeless chorus:

I turned 21 in prison doing life without parole

No one could steer me right

But Mama tried, Mama tried

Mama tried to raise me better, but her pleading I denied

That leaves only me to blame

’Cause Mama tried

“Sing Me Back Home” is another primal tale, one that sees a man in prison going off to his execution, asking a friend to play a last song for him:

The warden led the prisoner down the hallway to his doom

I stood up to say good-bye like all the rest

I heard him tell the warden just before he reached my cell

‘Let my guitar-playing friend do my request’Sing me back home with a song I used to hear

Make my old memories come alive

Take me away and turn back the years

Sing me back home before I die

It would do Merle Haggard a disservice not to note that he was, like any good country artist, a chucklehead now and again, and sometimes more often than necessary. Loosely associated with the outlaw country movements of the mid-1970s — a motley crew centered around the work of an ornery cuss named Waylon Jennings and a somewhat more mystical pothead named Willie Nelson — he set himself apart with his more, ah, traditional adherence to country verities. A hard-drinking, sometimes tokin’, and once-in-a-while outlandishly snortin’ kinda guy, he had no problem intoning songs about how great things used to be — back when “a joint was a bad place to be,” when “a girl could still cook and still would,” etc. Haggard went through some five wives, and I bet most of them thought from time to time about the good old days when husbands weren’t hellacious, cocaine-crazed, groupie-fucking assholes.

“Okie From Muskogee” is one of the great novelty songs of the era; a finely tuned not-quite-satire that at once celebrated traditional Americans discombobulated by changes in the country and blithely undercut them:

We don’t smoke marijuana in Muskogee;

We don’t take no trips on LSD

We don’t burn no draft cards down on Main Street;

We like livin’ right, and bein’ free.

The words read a little tough, but as sung they are amused and not really judgmental; the rest of the song is milder. There’s something gentle in the portrayal: If one of the big differences between the past and future is footwear, how bad could the divide really be?

But from there he went a bit further, taking a liking to the national attention he got from “Okie” and cheerfully playing up to the lumpen rural audience with a follow-up, “Fightin Side of Me.” This one isn’t amused at all, just a resentful bit of proto–Tea Party jingoism. “I wonder just how long the rest of us can count on being free,” he warns.

Haggard was always given props by the rock Establishment — Gram Parsons and Elvis Costello recorded his songs, and Dylan took him out on tour in the late 2000s — but he was somewhat set apart from this, as well. Part of it was that, on the old-time country model, he released a boatload of albums, most of them mediocre and even the good ones tattooed with filler. There are a lot of nice albums from the 1960s, when he was part of the Capitol Nashville machine; Sing Me Back Home, Bonnie and Clyde, Mama Tried, and Portrait are good places to start. The compilations of his I’m familiar with are frustrating, because they seems to be indifferently programmed (greatest-hits sets omitting some of his greatest hits) and even what would seem to be sure things (like the No. 1 collections) containing evanescent crap. It you want to do him up good, check out Down Every Road, a definitive four-CD set.

The one-time hippie-baiter got himself all leathered up and hirsute during the ‘70 and ‘80s. He became more genial and his shows, with the loyal and ever-precise Strangers behind him, were generally respectful approximations of the man. They let him be what he was: Something close to a legend.